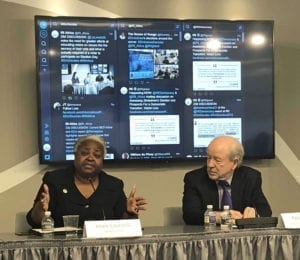

Solidarity Center Africa Regional Program Director Imani-Countess and NDI’s Patrick Merloe discussed challenges to democratic transition in Zimbabwe. Credit: Solidarity Center/Shayna Greene

Wage theft and other forms of economic injustice are among the major factors holding Zimbabwe back from a democratic transition, says Imani Countess, Africa regional program director for the Solidarity Center.

Countess spoke at a recent panel discussion in Washington, D.C., “Assessing Zimbabwe’s Election and Prospects for a Democratic Transition,” organized by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Bringing a labor perspective to the event, Countess described the strong correlation between increased participation in unions and the formation of other democratic institutions.

“There’s absolutely a link between democratic structures, the nature of unions and the role they play in the workplace, and in the nation and the fostering of broader democratic participation, particularly in elections,” says Countess.

Undemocratic practices flourish when workers are trapped in a cycle of economic inequality. Countess gave the example of 200 Zimbabwean women who experienced this type pf hardship firsthand after their husbands had not been paid for five years by the Hwange Colliery Co. Ltd. (HCCL). The company is one of the biggest in Zimbabwe, with the government as its largest shareholder.

Despite exporting to 13 nations including South Africa and China, HCCL owed its workers $70 million in unpaid wages. Often, companies will try to look attractive to foreign investors with competitive prices by engaging in forced labor and wage theft, Countess says.

Company’s Wage Theft Forced Families Turned to Informal Economy

The wives of the HCCL workers first protested in 2013 and were attacked by police. When they began protests again in 2018, they were joined by the Center for Natural Resource Governance, the National Mine Workers Union of Zimbabwe (NMWUZ) and the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions.

Although the mine workers are not union members, Zimbabwe unions stood by the women because they were “the wives of workers,” says Countess. “So the National Union of Mine Workers was there.”

To help feed their families, the women took on informal jobs such as selling in markets and cross-border trading. About 94 percent of Zimbabweans work in the informal economy. Of the 6 percent working permanent jobs, one-third are exposed to wage theft, especially in the extractive sector, says Countess.

“For five years, these women subsidized the Hwange Colliery Co. by supporting their husbands’ ability to work without pay,” she says.

Civil society groups helped mobilize the women in their campaign through workshops on nonviolent strategies for resistance and other skills-building strategies, and opportunities to exchange experiences with women in other mining communities.

Finally, demands were met, ensuring that the women’s husbands were paid and not retaliated against for the actions of their wives.

This is only one example of how unions promote democracy in Zimbabwe despite the country’s challenges, says Countess. Though Zimbabwe is a militarized state with an unenforced constitution, union members are active in community organizations and serve in national election observation groups. For instance, in 2013, unions came together representing 15 countries in the Southern Africa Trade Union Coordination Council (SATUCC) region to participate in an observation mission in Zimbabwe.

“Mass-based organizations working together with communities can be powerful actors of change,” says Countess.

Also on the panel were Patrick Merloe, senior associate and director for Electoral Programs at the National Democratic Institute, and Elizabeth Lewis, deputy director for Africa at the International Republican Institute.