Dec 15, 2021

Millions of migrant workers trapped in pandemic lockdowns were forced to leave their employers and return home—bearing all the costs even as they often were unpaid for the work they had performed, says Michael Joachim, co-founder and director of the Plantation Rural Education and Development Organization in Sri Lanka.

“Wage theft was already there, but then during COVID-19, it happened on a mass scale,” Joachim tells Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau on the latest episode of The Solidarity Center Podcast.

“Normally, a migrant worker would be paid a return ticket by the employer. Failing which, the host country in some way contributes to their return,” Joachim says. “So, nothing like that happened. The migrant worker had to pay his own money for the return ticket. Pay his own money for quarantine, pay his own money to get back home. So, he completely lost everything. Now, if you just imagine, a person who had borrowed money to go abroad.

“And then, he also borrows money to come back. Because, to come back also, for the return ticket, for quarantine, he had to still borrow money.”

Joachim’s organization is part of the Justice for Wage Theft Campaign, a global network of unions and migrant rights organizations, including the Solidarity Center, formed during the pandemic to push for governmental and employer reforms to ensure migrant workers have access rights fundamental to all workers.

Listen to This and All Solidarity Center Podcasts

Listen here to find out how the Justice for Wage Theft campaign is working to level the playing field for migrant workers or check it out on Spotify, Amazon, Stitcher or wherever you subscribe to your favorite podcasts.

Download all Solidarity Center episodes here and be sure to check out more episodes from Season Two:

The Solidarity Center Podcast, “Billions of Us, One Just Future,” highlights conversations with workers (and other smart people) worldwide shaping the workplace for the better.

Dec 10, 2021

Millions of workers around the world engage in paid labor—yet do not receive their wages. In addition, getting employers to pay workers what they are owed often is difficult—especially for those who have migrated for work, according to a new report from the Migrant Justice Institute.

“All of the risks and costs of wage recovery are placed with the party least able to bear them: the migrant worker,” says Laura Berg, co-executive director of the Migrant Justice Institute and co-author of the report, “Migrant Workers’ Access to Justice for Wage Theft.”

The report draws on a year of global consultations and analysis across all regions, identifying common drivers of wage theft to propose specific, practical reforms that can underpin global, national and local wage theft campaigns. It is co-authored by Migrant Justice Institute Co-Executive Director Bassina Farbenblum.

Wage theft—which also includes being paid less than the minimum wage, or not being compensated for overtime or sick leave—increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially for migrant workers who were required to return to their home countries at the start of the pandemic and who then had no recourse for obtaining their unpaid wages.

Wage theft—which also includes being paid less than the minimum wage, or not being compensated for overtime or sick leave—increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially for migrant workers who were required to return to their home countries at the start of the pandemic and who then had no recourse for obtaining their unpaid wages.

But the magnitude of wage theft prior to the pandemic makes clear it happens by design.

“Wage theft is not just the result of a few bad employers. It’s part of a business model in many supply chains,” said Elizabeth Frantz at the Open Society Foundations. Frantz moderated a Migrant Justice Institute virtual panel December 7 to launch the report. (Watch the full event here.) OSF funded the report and virtual panel.

Speaking at the event, Jill Wells, with Engineers Against Poverty, described how a complex system of supply chain contracting in Qatar, where she worked on construction for the 2022 World Cup, often led to wage theft for migrant workers. Without laws and enforcement mechanisms to ensure migrant workers get compensated, even private organizations can only go so far to assist migrant workers, said Ben Harkins at the International Labor Organization (ILO), which has established Migrant Resource Centers in several Asian countries.

“Let’s be clear—this is not just a simple issue of wage arrears as many try to classify the issue, as if it’s just a clerical error. This is theft. And it’s outrageously common and getting worse during the pandemic,” said Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau, who took part in the panel. The Solidarity Center and the International Lawyers Assisting Workers (ILAW) network supported the report and organized the regional consultations.

Holding Employers Accountable, Expanding Labor Laws

A big barrier to accessing justice is migrant workers’ fear of employer retaliation. “Most migrant workers are unlikely to file a claim because they fear being deported, losing their job or other forms of retaliation,” the report says.

Although the report finds no single solution will ensure migrant workers receive their due compensation or can access justice if they do not, it details measures government officials and employers should take. For instance, migrant workers should receive permission to stay in country to pursue wage claims. If they return home without pay, they should be able to lodge wage claims through video testimony or online courts.

Because the system generally favors employers, migrant workers are forced to prove their claims, and it is extremely difficult for migrant workers to provide evidence of their work and the unpaid wages. The report recommends shifting the burden of proof to employers with legal presumptions in workers’ favor regarding duration of employment hours worked, wages owed and so on.

Holding employers accountable also is essential. “Employers facing a wage judgment simply liquidate or refuse to pay. They won’t be held responsible by suppliers or contractors,” said Berg. The report lists options for enforcing a determination and collecting payment, such as holding licensing of employers, deregistering a business and suspending orders until workers receive what they are owed.

Freedom to Form Unions Key to Migrant Worker Rights

Governments must extend labor law coverage to all workers, according to the report. Most migrant workers are not protected by labor laws, which establish minimum wages, job safety and health guidelines, and social protection coverage like paid sick leave and time off. And, most migrant workers are prohibited from forming unions to collectively champion decent working conditions.

The most marginalized workers are especially vulnerable to wage theft, and debt incurred when they are unpaid renders them vulnerable to forced labor, said Franz.

“This study focuses on initiatives by governments and state actors, but recognizes that often those mechanisms just aren’t enough,” said Bader-Blau. “To truly recover stolen wages and ensure migrant worker justice, this has to be combined with collective action of migrant workers around the world.”

Fundamentally, says Bader-Blau, “We must continue to support freedom of association, the right to organize and collectively bargain for all workers regardless of their nationality, gender, sector or immigration status as the primary mechanism to prevent and address rampant wage theft of migrant workers.”

Says Frantz: “It’s clearly time for business and government to recognize that it is ethically unacceptable to let the risks and burdens of wage recovery lie with migrant workers rather than business and government.”

Panel participants also included Terri Gerstein from the Harvard Labor and Worklife program; Douglas Maclean, Justice Without Borders; and Apolinar Tolentino, Building and Wood Working International.

The report is part of an ongoing global campaign titled Justice for Wage Theft organized by Building and Wood Workers’ International (BWI), Migrant Forum in Asia, Lawyers Beyond Borders Network, Cross Regional Centre for Migrants and Refugees, South Asia Trade Union Council (SARTUC), ASEAN Services Employees Trade Union Council and the Solidarity Center.

Jun 21, 2018

Solidarity Center Africa Regional Program Director Imani-Countess and NDI’s Patrick Merloe discussed challenges to democratic transition in Zimbabwe. Credit: Solidarity Center/Shayna Greene

Wage theft and other forms of economic injustice are among the major factors holding Zimbabwe back from a democratic transition, says Imani Countess, Africa regional program director for the Solidarity Center.

Countess spoke at a recent panel discussion in Washington, D.C., “Assessing Zimbabwe’s Election and Prospects for a Democratic Transition,” organized by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Bringing a labor perspective to the event, Countess described the strong correlation between increased participation in unions and the formation of other democratic institutions.

“There’s absolutely a link between democratic structures, the nature of unions and the role they play in the workplace, and in the nation and the fostering of broader democratic participation, particularly in elections,” says Countess.

Undemocratic practices flourish when workers are trapped in a cycle of economic inequality. Countess gave the example of 200 Zimbabwean women who experienced this type pf hardship firsthand after their husbands had not been paid for five years by the Hwange Colliery Co. Ltd. (HCCL). The company is one of the biggest in Zimbabwe, with the government as its largest shareholder.

Despite exporting to 13 nations including South Africa and China, HCCL owed its workers $70 million in unpaid wages. Often, companies will try to look attractive to foreign investors with competitive prices by engaging in forced labor and wage theft, Countess says.

Company’s Wage Theft Forced Families Turned to Informal Economy

The wives of the HCCL workers first protested in 2013 and were attacked by police. When they began protests again in 2018, they were joined by the Center for Natural Resource Governance, the National Mine Workers Union of Zimbabwe (NMWUZ) and the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions.

Although the mine workers are not union members, Zimbabwe unions stood by the women because they were “the wives of workers,” says Countess. “So the National Union of Mine Workers was there.”

To help feed their families, the women took on informal jobs such as selling in markets and cross-border trading. About 94 percent of Zimbabweans work in the informal economy. Of the 6 percent working permanent jobs, one-third are exposed to wage theft, especially in the extractive sector, says Countess.

“For five years, these women subsidized the Hwange Colliery Co. by supporting their husbands’ ability to work without pay,” she says.

Civil society groups helped mobilize the women in their campaign through workshops on nonviolent strategies for resistance and other skills-building strategies, and opportunities to exchange experiences with women in other mining communities.

Finally, demands were met, ensuring that the women’s husbands were paid and not retaliated against for the actions of their wives.

This is only one example of how unions promote democracy in Zimbabwe despite the country’s challenges, says Countess. Though Zimbabwe is a militarized state with an unenforced constitution, union members are active in community organizations and serve in national election observation groups. For instance, in 2013, unions came together representing 15 countries in the Southern Africa Trade Union Coordination Council (SATUCC) region to participate in an observation mission in Zimbabwe.

“Mass-based organizations working together with communities can be powerful actors of change,” says Countess.

Also on the panel were Patrick Merloe, senior associate and director for Electoral Programs at the National Democratic Institute, and Elizabeth Lewis, deputy director for Africa at the International Republican Institute.

Jul 15, 2016

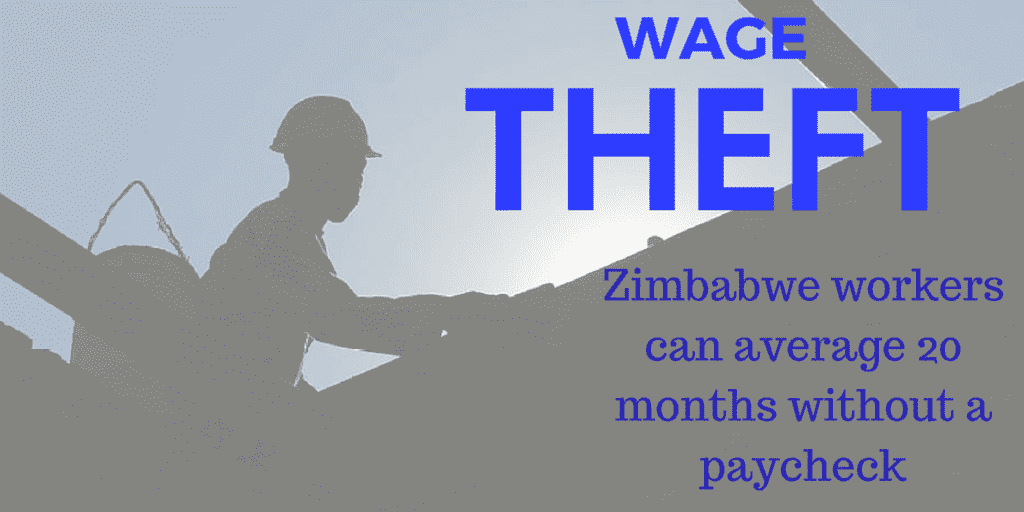

An astounding 80,000 Zimbabwe workers in formal employment—out of some 350,000 workers—did not receive wages and benefits on time in 2014, according to a new Solidarity Center report, “Working Without Pay: Wage Theft in Zimbabwe,” released today in Harare.

As a result of this widespread wage theft, many workers say they are forced to eat only one or two meals a day; move repeatedly to access affordable housing; and rent two rooms or fewer for their entire family to make ends meet.

As a result of this widespread wage theft, many workers say they are forced to eat only one or two meals a day; move repeatedly to access affordable housing; and rent two rooms or fewer for their entire family to make ends meet.

Through first-person interviews and other research by affiliates of the country’s main trade union confederation, the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU), the report provides hard data behind last week’s successful one-day shut-down of businesses, government and services by workers across Zimbabwe outraged over wage theft and a new law targeting market vendors who make up the vast proportion of the workforce.

Paid Only Enough to Get to Work

One woman interviewed in the report, whose experience is not uncommon, says she has received $26 a month in wages for the past eight months, although her monthly salary is $342. Yet basic living costs, which on average include $60 for renting a single room, $30 for electricity, $15 for water and $22 for transportation to work, mean she only has sufficient funds to get to and from her job.

“This failure to pay what workers are legally entitled to is wage theft in that it involves employers taking money that belongs to their employees and keeping it for themselves,” the report states. “This is a clear violation of international labor standards, as well as national legislation on the employment of workers.”

The report traces the ongoing wage theft to 2012, as employers in the public- and private-sector increasingly began delaying wage payments.

Up to 95% of Zimbabweans Work in Informal Economy

Simultaneously, the number of jobs in the informal economy has skyrocketed, the report points out. Some 6.3 million people made up Zimbabwe’s workforce in 2014, of which 5.9 million workers (94.5 percent) were informally employed, compared with 84.2 percent in 2011, according to “Working without Pay.” An additional 800,000 women and men were in the workforce, but unemployed.

Last month, the government introduced a statutory law that bans imports of basic commodities—a law that directly affects hundreds of thousands of informal economy workers who survive on cross-border trading. Up to 95 percent of jobs in Zimbabwe are in the informal economy, and workers say the new law takes away their livelihoods.

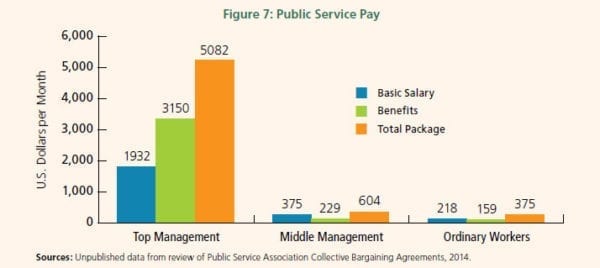

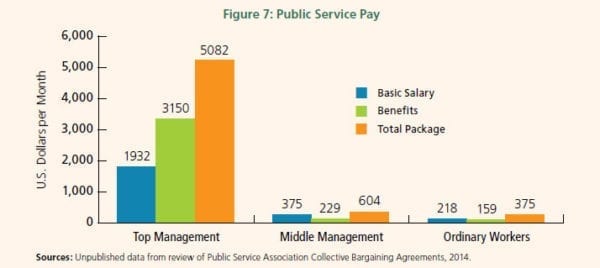

Based on surveys at 442 companies, and the result of extensive research by the Labor and Economic Development Research Institute of Zimbabwe, the report also documents extravagant salaries and benefits to middle and top management even as workers go unpaid and presents recommendations for action to address the problem.

Companies Involved in Wage Theft Must Be Held Accountable

Some of the recommendations include:

- The Ministry of Labor, together with representatives of employers and unions, should review the status of companies that are not paying their workers and assist in developing plans to rectify the injustice.

- Unions representing workers in companies not paying salaries—in full and on time—should demand that the government bring criminal proceedings under the relevant provisions of the Labor Act against employers.

- Trade unions should advocate for payment of interest on late payment.

- The government should set an example by reviewing the wage structure in government agencies and quasi-government agencies to limit benefits to top managers, institute a more just pay scale and prioritize payments to workers through collective bargaining or social dialogue.

Wage theft—which also includes being paid less than the minimum wage, or not being compensated for overtime or sick leave—increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially for migrant workers who were required to return to their home countries at the start of the pandemic and who then had no recourse for obtaining their unpaid wages.

Wage theft—which also includes being paid less than the minimum wage, or not being compensated for overtime or sick leave—increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially for migrant workers who were required to return to their home countries at the start of the pandemic and who then had no recourse for obtaining their unpaid wages.