Aug 23, 2018

Two female migrant workers from Myanmar were arrested in Thailand, fined and await deportation for volunteering their time to teach children of migrant workers at a Buddhist monastery, an action the Thailand-based Human Rights and Development Foundation (HRDF) is calling “illegitimate and unjustified.”

The two women, who hold valid passports, visas and work permits, volunteered at the Laem Nok Monastery in southern Thailand in addition to the jobs for which they were hired. But immigration officials charged them with performing work without a permit to teach, even though the time they spend instructing the children is unpaid, according to HRDF and the Migrant Working Group (MWG). The MWG is a network of non-governmental organizations working on health, education and migrant workers’ rights that includes the Solidarity Center.

The arrests occurred despite the statement of one worker’s employer who told police the worker is lawfully employed and has been excused to take leave from her regular job painting boats because she is pregnant. The monastery also affirmed the two workers taught without pay, actions that are not illegal in Thailand, says HRDF, a Solidarity Center partner.

The women were forced to sign a document in Thai that they did not understand, in which they admitted they committed a crime, and received a fine of 5,000 Baht ($153) in lieu of imprisonment. They will be banned from re-entering to work in Thailand for two years, according to HRDF. A Myanmar national holding a tourist visa who observed the volunteers teaching was also arrested on the same charge.

“The arrests could signal a strong discouragement to other similar teaching programs in the country and could also pose a negative impact on education opportunities for migrant children as a whole,” HRDF and MWG said in a statement.

Volunteers Taught Children at Risk of Exploitation

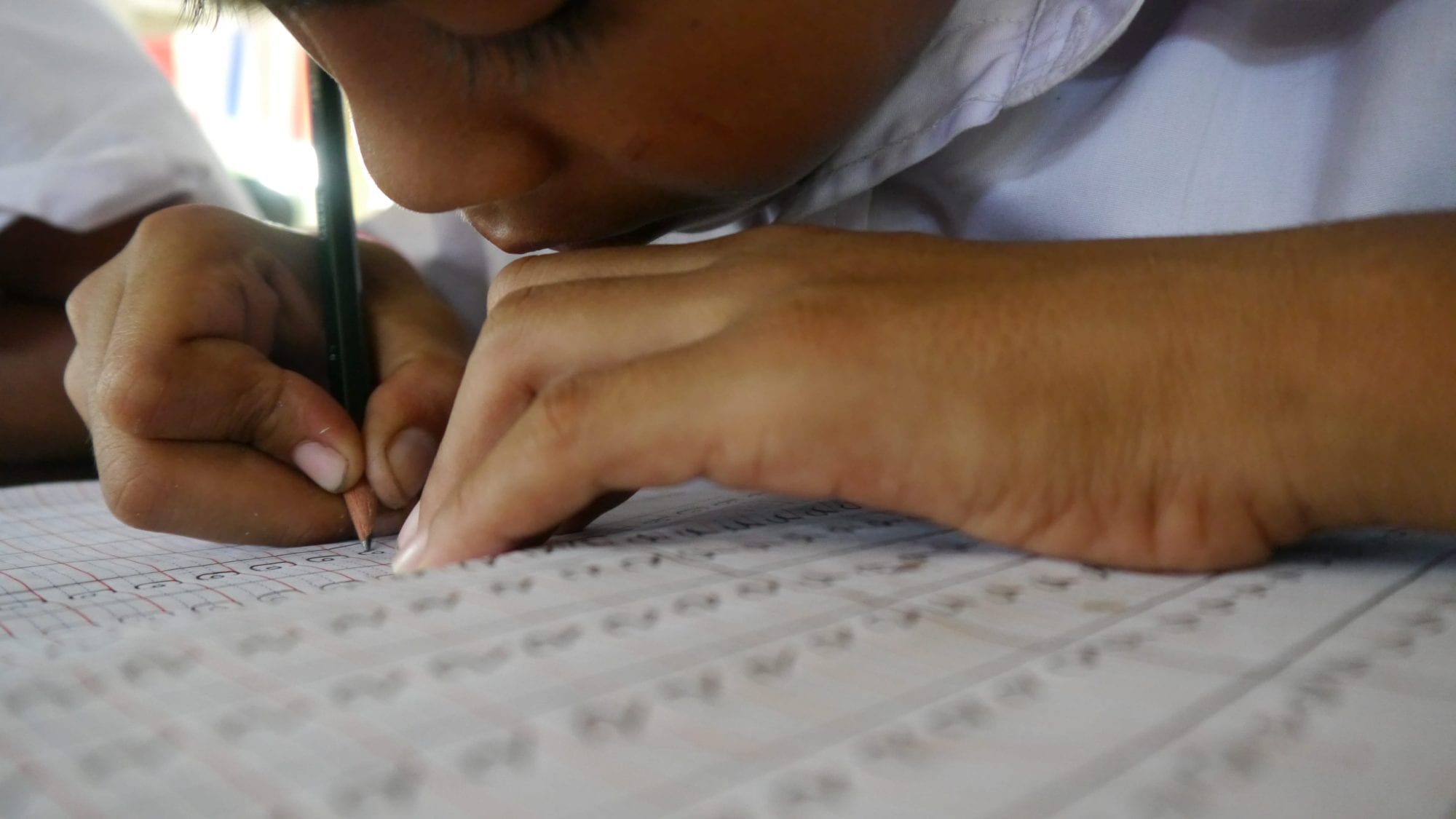

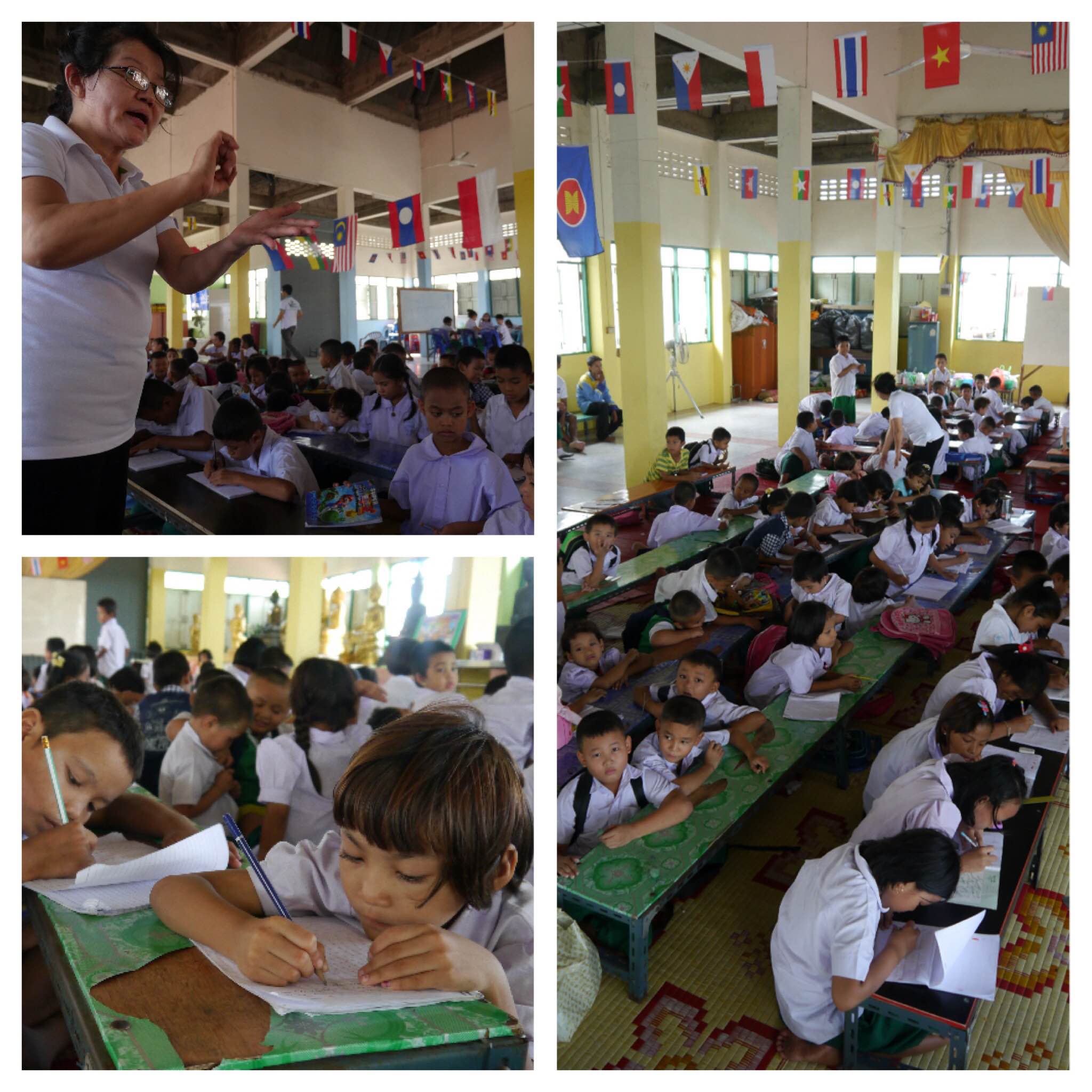

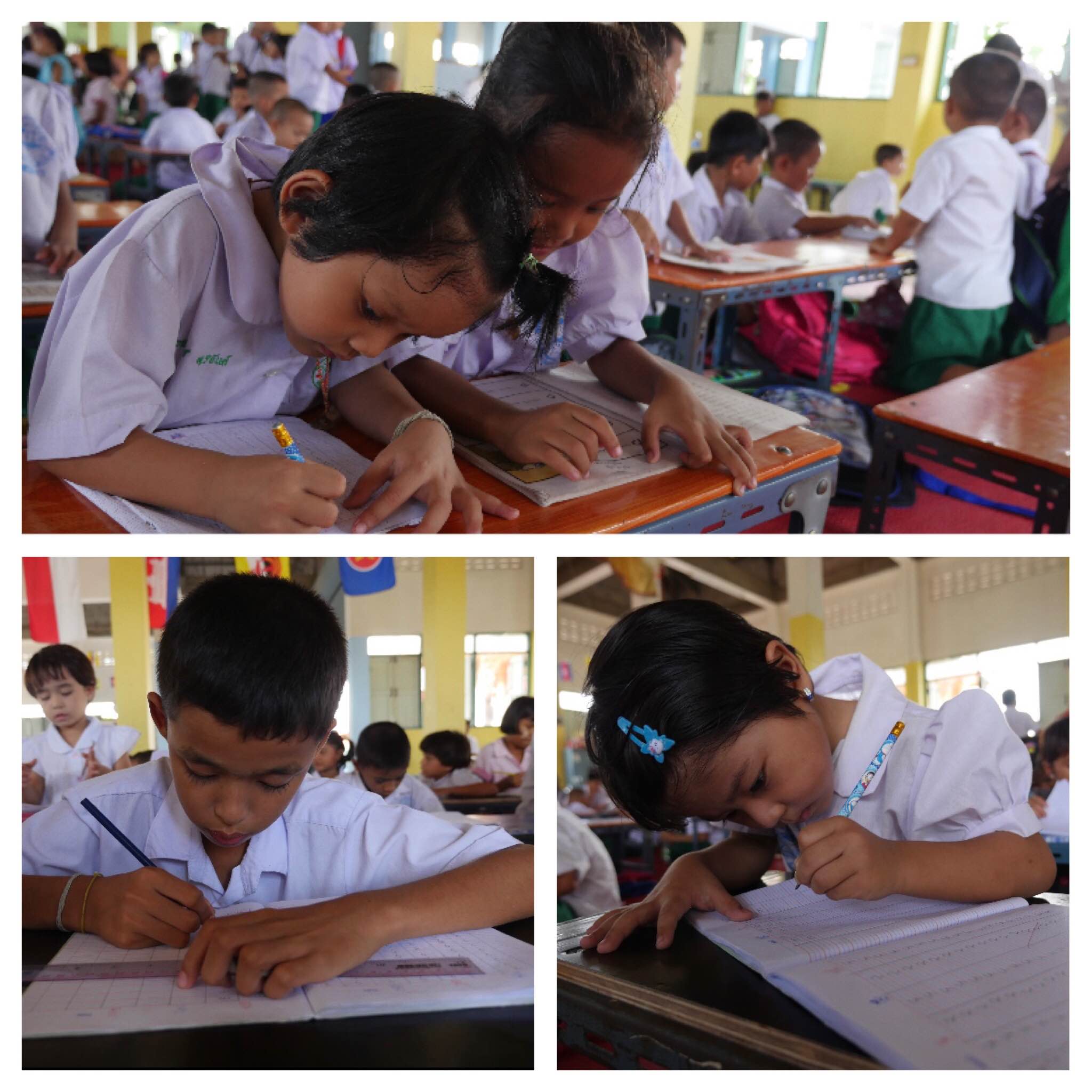

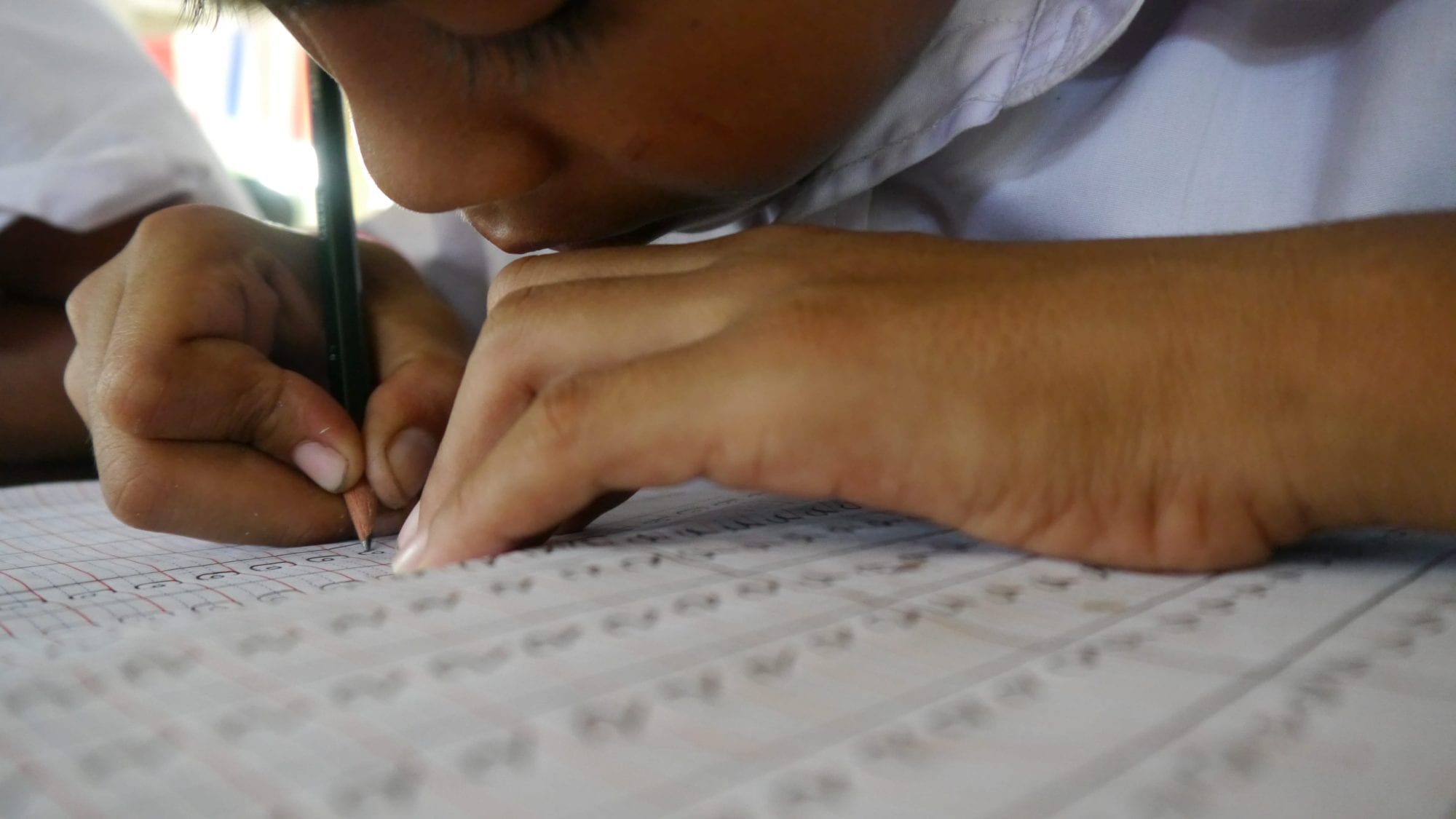

The Laem Nok Monastery has operated a learning center for children of migrant workers for more than four years. The program began after the community recognized that migrant children, who are often left without care when their parents are working can be targets of forced labor, human trafficking and other forms of exploitation. With support from community fundraising, the monastery dedicated a learning space where children are taught the languages and cultures of Thailand as well as those of their origin countries. Local businesses provide funding for food and teaching supplies, but the teachers are unpaid volunteers, including local college students.

HRDF and MWG are calling on Thailand’s Department of Employment, Ministry of Labor to establish clear guidelines for enforcing compliance with work permits and to review the policy that restricts migrant workers from becoming paid or unpaid volunteers.

The groups also are urging police to ensure migrant workers’ legal rights are respected, including the right to legal counsel and to bail during pre-trial.

“The arrests have created undeserving traumas to the children in the classroom who had to witness their teachers being arrested and taken away in front of them,” says HRDF.

Jul 31, 2018

The migrant children diploma center opened in 2013 as the first school for children of Burmese migrant workers in the community known as “little Burma” located an hour outside Bangkok in Mahachai, Thailand.

Thousands of children accompany their parents who are among the estimated 200,000 Burmese migrant workers in Mahachai.

The school is supported through donations from private companies, religious organizations, and migrant workers who contribute 60 Thai baht (USD 1.68) a month to pay the salaries of the seven teachers.

More than 200 students attend this elementary school based in a Buddhist temple. For many of them, it is their first experience with formal education.

NOW IS NOT THE TIME FOR KIDS TO WORK

When parents are protected at work, kids can go to school.

Jul 18, 2018

Worker rights advocates are hailing a recent court decision in Thailand that dismissed criminal defamation charges against 14 migrant workers from Myanmar who faced jail time after reporting abusive working conditions on a poultry farm.

Fourteen workers who left the farm in 2016 described forced overtime, unlawful salary deductions, confiscation of passports and restrictions on freedom of movement in a complaint to the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand.

In retaliation against the workers for submitting the complaint, the Thammakaset Co. Ltd. filed a criminal defamation complaint against the 14 workers, alleging they falsified claims to damage its business interests.

The case put a spotlight on abuse in the supply chain, says Solidarity Center Asia Regional Director Tim Ryan. The ruling “strikes a blow against the criminalization of promoting labor rights,” and is a landmark for migrant worker rights and freedom of expression.

“Companies filing criminal defamation complaints against workers who seek justice on the job is an all-too common practice, one often used as justification for dismissal. This decision is in line with international legal standards supporting free speech, freedom of assembly and other activities key to an open civil society.”

Workers Increasingly Migrate for Jobs

One of the migrant workers says he worked 22-hour shifts for more than four years at the Thammakaset 2 Poultry farm, which supplies one of Thailand’s largest chicken export companies. Myint told the Guardian that each day, he would kill up to 500 birds for food processing. At night, he and his co-workers say they slept on the floor in a room with up to 28,000 chickens, swatting away insects. If a bird got sick, they were to blame.

Of the 232 million migrants around the world, 150 million are migrant workers. Millions of migrant workers like Myint and his co-workers are unable to find family-supporting jobs in their origin countries. With labor migration increasing as men and women seek to support their families, the case highlights the rights of migrant workers seeking justice for workplace abuse.

A team of United Nations human rights experts this year called on Thailand to “end recurring attacks, harassment and intimidation of human rights defenders, union leaders and community representatives who speak out against business-related human rights abuse.”

Referring to the Thammakaset case, they said “business enterprises have a responsibility to avoid causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts; therefore it is a worrying trend to see businesses file cases against human rights defenders for engaging in legitimate activities.”

Thammakaset also filed a criminal complaint against two of the 14 workers and a Migrant Worker Rights Network coordinator for the alleged “theft” of time cards, taken by the workers to show labor officials evidence of their claims about a 20-hour working day. MWRN, a Solidarity Center partner, is a membership-based organization for migrant workers from Myanmar working in Thailand.

Jun 5, 2018

Rural Cambodian villagers who say they were trafficked for forced labor in the shrimp processing industry in Thailand are challenging a ruling by a California federal district court that dismissed their case against the Thai and U.S. companies that benefited from their labor.

A coalition of human rights groups, led by the Solidarity Center, filed an amicus brief on June 1 in support of seven workers as their case goes to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The workers had brought their suit based in part under the U.S. Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA), which in 2008 was amended to extend civil liability to those who “knowingly benefit” from the trafficking of persons in their supply chains.

The December ruling of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California interpreted the TVPRA in a way that essentially ignored the “knowingly benefit” standard and instead required evidence that the U.S.-based companies actually participated in a venture to traffic the Cambodian workers into Thailand, according to Solidarity Center Legal Director Jeff Vogt.

The supporting brief argues, in part, that the companies knew or should have known of the widespread use of trafficked labor in the seafood sector in Thailand. Since 2008, numerous reports have exposed the trafficking of workers into Thailand to work in the shrimp industry. It would have been virtually impossible for enterprises involved in the shrimp industry not to have known of the extremely high risk of trafficking.

In 2016 alone, 16 million people were victims of forced labor by private enterprises, according to International Labor Organization estimates. This illegal activity generates $51 billion in profits.

Following the December court ruling (Keo Ratha, et al. v. Phatthana Seafoods Co. Ltd., et al.), Keo Ratha, one of the seven men filing the suit, told Voice of America Khmer that he deeply regretted the district court’s decision.

“I’m disappointed because we thought that the U.S. court would find justice for us,” he said. “But when the court dismissed our complaint I was speechless. This is their law.”

Joining the Solidarity Center in its brief are the Centro de los Derechos del Migrante, Earthrights International, the International Labor Recruitment Working Group, the International Labor Rights Forum and the Worker Rights Consortium.

Feb 6, 2018

Apantree Charoensak, union president, was fired from her position at Yum! Thailand during contract negotiations. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

Some 2,000 fast food workers and supervisors at one of Thailand’s largest KFC franchises recently won the first-ever collective bargaining agreement in the kingdom’s fast food industry, a pact that includes an early retirement program, 23 meals provided by the company per year and motorcycle maintenance funds for delivery workers.

The contact also includes the right to union representation in any dispute or grievance, and paid union leave.

The workers are among 2,400 members represented by the Cuisine and Service Workers’ Union, an IUF affiliate.

During negotiations last month, union President Apantree Charoensak, who has been leading the struggle for fast food workers across Thailand for nearly a decade, was fired from her position at Yum! Thailand, which operates some of the KFC franchises. (The new contract covers KFC franchises run by Restaurant Development Ltd., which operates 130 of the 586 KFC restaurants in Thailand.)

Women representing 50 organizations in Thailand issued a statement of solidarity with Charoensak and submitted it to management of Yum! Thailand in Bangkok. Charoensak, along with two co-workers, had been previously dismissed in 2011 following her efforts to organize a union and negotiate a contract with Yum! Thailand. She and her co-workers were reinstated after filing a complaint with the country’s Labor Relations Commission describing their dismissal as retaliation for union activity, an action prohibited under Thai law.

Charoensak, a manager at the corporation where she supervised up to a dozen restaurants, says she began union organizing to rectify what she saw as a large pay disparity between front-line workers and managers. Ultimately two unions formed, one covering front-line employees and one for supervisors. Over the years, she says management also tried to end her union activism by offering her large sums of money, which she refused, and isolated her at work, giving her little to do—time she filled by completing a master’s degree in political science and addressing union members’ concerns.