Feb 3, 2022

“The dignity of people’s very being is at stake,” said IZWI Domestic Worker Alliance’s founder and lead researcher Amy Tekie in opening remarks at a recent webinar focused on a new qualitative survey of human rights violations against live-in domestic workers in South Africa.

“Really awful things are happening behind closed doors,” said IZWI’s Amy Tekie.

“The Persistence of Private Power: Sacrificing Rights for Wages“—co-published by Johannesburg-based IZWI Domestic Workers Alliance and the Solidarity Center—surveys the constitutional and human rights of live-in domestic workers in South Africa. It describes how domestic workers’ rights to privacy, freedom of movement and children’s right to parental care are frequently sacrificed for wages in a sector underpinned by racism, sexism and classism. Resulting exploitation—largely invisible because of the private spaces in which it occurs—continues regardless of constitutional protections and industry-specific labor regulations.

We are expected to be indoors even when it is our off day,” said the survey’s lead field researcher Theresa Nyoni. Credit: IZWI

“We are not allowed to be seen around,” said the survey’s lead field interviewer, Theresa Nyoni, of a sectional title housing complex in which she was formerly employed as a domestic worker.

Nyoni described almost universally denied opportunities for live-in domestic workers in sectional title housing to enjoy open spaces on, or near, the employers’ property and lack of freedom to move around or receive visitors in their own quarters—even during off hours. And, for most live-in domestic workers, she noted invasive employer surveillance and almost total lack of privacy.

“We are sleeping with kids and not allowed to lock the door; parents barge into the room and even the bathroom,” she said.

Employers isolate domestic workers by routinely denying them visits from friends, spouses and children, and some domestic workers say they are not allowed to leave their employer’s home for any reason. Nyoni described her former employer’s refusal to allow her to leave the work premises, on her own time, to purchase and arrange for transportation of bulk food items to her own children during the pandemic.

“When I held a plate of food to eat, I was thinking: Did my children get food today?”

Survey interviewees outlined living conditions that Tekie described as “almost kidnapping [in its] constant and complete employer surveillance and control.” Besides being isolated from loved ones, many live-in domestic workers said they were denied employer permission to keep their infants with them, receive packages or use their employer’s kitchen to preserve and prepare their own food, and those employed in sectional title housing complexes reported repeated employer and security guard searches. Some live-in domestic workers said they have chosen abortions for fear of losing their jobs.

IZWI interviewed 115 mostly migrant live-in domestic workers for the survey, most of whom were working in or near Johannesburg—where working conditions are anecdotally better than those than in rural areas, said Tekie. Approximately half of South Africa’s more than 800,00 domestic workers live in by IZWI’s estimate, although definitive data does not yet exist, she said.

The survey affirms that state silence perpetuates the status quo, said McGill University Faculty of Law Professor Adelle Blackett.

McGill University Faculty of Law Professor of Transnational Labor and Development Adelle Blackett underscored the significance of the report being centered on the lived experience of domestic workers and the persistence of private power in their lives, even post-Apartheid.

Describing the report as “chilling,” Blackett defined the status quo for South Africa’s domestic workers as, “historicized, racialized, intersectionalized enslavement to domestic servitude.”

“[This report] is only the tip of the iceberg,” said former South African Labor Court judge Urmilla Bhoola.

The survey illustrates that translating South Africa’s laudable rights into reality for domestic workers is a tremendous challenge, said former South African Labor Court judge and former United Nations Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Slavery and panelist Urmilla Bhoola.

“When domestic workers live in, they forfeit their rights,” she said. And so, civil society legal activism is essential, including that spearheaded by trade unions, she added.

Report recommendations include extension to domestic workers of many of the rights contained in South Africa’s farmworker Extension of Tenure Security Act (ESTA) but absent from Sectoral Determination 7 governing domestic work. ESTA guarantees to farmworkers residing on employers’ land “the right to human dignity”—including privacy, having family life, the freedoms of association, movement and religion, and to have visitors and receive postal communication.” Alternatively, concludes the report, legislation specific to the domestic work sector should be created that includes:

- Minimum housing standards for all live-in domestic workers, not only those paying rent

- Basic regulations on rights to family life and visitors, including the right for family to cohabit with a worker, within residential density laws, and the right for workers to have visitors in their homes

- Regulations to protect privacy, explicitly preventing employers from searching rooms, phones or property without permission

- Clear protection of a worker’s right to move freely during off hours

- Guidelines on bullying, harassment and assault, as those provided in the labor law do not address the specifics of the domestic sector

- Guidelines for provision of food.

Jun 15, 2021

On June 16 International Domestic Workers Day, domestic workers are celebrating a landmark legal win by South Africa’s domestic workers for colleagues who die or are injured in their employers’ homes. For the first time, starting this year, domestic workers who suffer injury on the job are eligible for compensation for temporary and permanent disability, medical expenses, funeral costs and survivor benefits.

Until last year, South Africa’s approximately 1 million privately employed domestic workers suffered deaths and crippling injuries without access to compensation for themselves or their dependents because domestic workers were excluded from South Africa’s Compensation for Occupational Injury and Illness Act (COIDA). With Solidarity Center support, the South African Domestic Service and Allied Workers Union (SADSAWU) and human rights organization Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (SERI) litigated and won a long-denied claim for the dependent daughter of Maria Mahlangu, a privately employed and partially sighted domestic worker who had fallen into her employer’s swimming pool and drowned in 2012. The historic judgment, made by the South African Constitutional Court in mid-November, recognized that injury and illness arising from work as a domestic worker in a private home is no different to that occurring in other workplaces and thus equally deserving of COIDA coverage.

Myrtle Witbooi, general secretary of SADSAWU and the first president of the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF), said in addition to the last year’s court ruling, South Africa’s domestic workers can also celebrate this year’s hard-fought win under revised compensation rules of three years of retroactivity to submit claims.

Under the new rules, all employers of domestic workers must register with the Compensation Fund or face penalties, and make annual payments to cover their employees. SADSAWU is focusing its efforts on educating employers and domestic workers about their obligations and rights under the new rules, says Witbooi. SERI made a new domestic worker compensation information fact sheet available to domestic workers, paralegals and community advice offices this month, while SADSAWU is producing and distributing an educational WhatsApp video and pamphlet and translating the amendment into local languages.

The unions and SERI continue to press the government for more time for domestic workers to submit claims and increase retroactivity. “We must remain that beacon of hope for workers,” says Witbooi.

Meanwhile, another domestic worker, Nobuhle Ndlovu, drowned in her employer’s swimming pool last month.

Ten years after the adoption of an International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention confirmed their labor rights, domestic workers across the globe are still fighting for recognition as workers and essential service providers, as documented by a new ILO report. And, although 32 countries have ratified Domestic Workers Convention 189, and 29 have entered the convention into force, most of the world’s 75.6 million domestic workers are still being denied social protection rights, including access to national health insurance, pension schemes and compensation funds.

Apr 28, 2021

Women working in South Africa’s mining sector report being subject to sexual and gender-based violence and harassment, inside mines and within the mining communities where they live and efforts to redress such abuse must address the nature of the workplace and political, social and economic factors.

Download here.

Apr 28, 2021

Women working in South African mines “at times confront danger, violence and indignity in their work environments,” where gender-based violence and harassment (GBVH) appears both widespread and normalized, according to a new report from the Solidarity Center and South Africa-based Lawyers for Human Rights (LHR).

The report, “What Happens Underground Stays Underground: A Study of Experiences of Gender-Based Violence and Sexual Harassment of Women Workers in the South African Mining Industry,” found that while verbal harassment is most common, women mineworkers also face requests for sexual favors in exchange for physical labor or for promotions, transfers or changes in work schedules. And sexual assault and harassment can occur both above and below ground at mines.

GBVH in the mining sector can be attributed to a range of complex political, social and economic factors, including:

- The dark and isolated nature of underground mines makes GBVH more likely, and monitoring and supervision of workers and evidence collection more difficult.

- South Africa’s dominant patriarchal social norms are exacerbating reporting barriers by enabling a culture of silence and victimization and the economic dependency of women on men.

- Women working within the numerically and culturally male-dominated sector are outnumbered and often subordinated in their personal security and professional development.

- Some business strategies are undermining the well-being of women workers in the mining industry, such as the outsourcing of female worker recruitment, which can expose recruits to sexual exploitation by gatekeepers of lucrative jobs, and the failure to accommodate women in the design and placement of facilities such as bathrooms, locker rooms, bus stops and elevators, which leaves women vulnerable to violence and harassment.

The report’s findings and recommendations are based on interviews conducted in Cape Town, Johannesburg, KwaZulu-Natal, Mpumalanga, Rustenburg and Wonderkop last year with former and current women mineworkers and representatives of women’s structures within mining unions, including the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), the Center for Applied Legal Studies at Wits (CALS), the South African Gender Equality Commission, the South African Human Rights Commission and the Wits Mining Institute. All women mineworker interviewees chose to remain anonymous, to protect their safety and jobs.

“Women mineworkers, striving to support their families, live a troubling reality—one that comes at great cost to their physical and mental well-being. The stakes are high, and the failure to prevent GBVH amounts to granting tacit permission to perpetrators,” according to the report.

Lead report researcher Sheila B. Keetharuth—who previously served on the United Nations team of international experts on the Kasai, Democratic Republic of Congo—says that the lower proportion of female workers in the mining sector in South Africa is, “a recipe for disaster that necessitates easily accessible and trustworthy reporting mechanisms as provided for in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.”

The International Labor Organization two years ago adopted Convention 190, the first global binding treaty to address GBVH in the world of work. The treaty calls on governments, employers and unions to work together to confront the root causes of GBVH, including the multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination, gender stereotypes and unequal gender-based power relationships. South Africa has yet to ratify Convention 190.

“Safe and healthy jobs are among workers’ most fundamental rights,” says Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau. “As we observe World Day for Safety and Health at Work today, we must continue to reinforce that a safe workplace is one that is free of gender-based violence and harassment. And through unions, workers can achieve the strong, collective voice needed to improve safety and health on the job.”

Report recommendations include that:

- South Africa immediately ratify ILO C190 on Violence and Harassment at Work

- Occupational health and safety laws and policies, as well as sector-specific laws and policies, obligate employers to prevent and eliminate GBVH

- The country’s Mining Charter extend employer obligations with respect to prevention and elimination of GBVH and require that special measures be adopted for women working in mining

- In consultation with workers and unions, compulsory GBVH risk assessments be established for identifying safety risks.

- Acquisition of a mining license be conditioned on right holders’ commitment to the prevention and elimination of GBVH

- Employers adopt confidential and independent reporting system

- Women working underground be provided with a confidential, anonymous, efficient and easily accessible incident reporting system.

- Workers be informed that victims of sexual assault have the right to press separate criminal or civil charges against their perpetrators.

- Mandatory and effective education and training with respect to laws and policies on GBVH be provided to workers and supervisors, and that policies addressing GBVH be printed in all official languages, displayed conspicuously throughout the mining shafts, and widely and regularly promoted through interactive workshops.

- Policies against GBVH be included in employment contracts and clearly state repercussions for GBVH violations.

- The mining industry provide education and counseling to rehabilitate perpetrators in cases not likely to reach the level of criminal prosecution.

“Although the report shows that GBVH is rooted in complex and deeply entrenched patriarchal social norms, it also presents fairly simple, cost-effective changes to the work environment—such as improved lighting, a buddy system and safer toilet and locker room locations—that will make women mine workers less vulnerable to crimes of opportunity,” says Solidarity Center Rule of Law Department Senior Program Officer Ziona Tanzer.

Beginning in 2014, the Solidarity Center was a core member of a global coalition of worker rights organizations led by women union activists that successfully advocated for Convention 190. We support our partners as they campaign for their governments to ratify ILO Convention 190 and recognize GBVH as a primary barrier to achieving gender equality and a key step for security of all workers’ rights and seek to enhance the voice of women and other marginalized workers in policy making at the local, national, and international levels to reduce the risk of gender-based violence at work—including through their unions.

Mar 10, 2021

“Violence and harassment happens to all workers, irrespective of your gender,” says Brenda Modise, a union activist in South Africa. “It doesn’t matter whether they are men and women, old young LGBTQI community or anyone, but we are addressing violence and harassment in the world of work against all workers.”

Modise spoke with Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau in first episode of The Solidarity Center Podcast, “Billions of Us, One Just Future,” which highlights conversations with workers (and other smart people) worldwide shaping the workplace for the better.

(Join us for a new episode each Wednesday at iTunes, Spotify, Amazon, Stitcher or wherever you listen to your podcasts. )

Front-line Leaders Building a Future Inclusive of All Workers

The Solidarity Center Podcast’s seven-episode season will feature worker advocates from around the world:

The Solidarity Center Podcast’s seven-episode season will feature worker advocates from around the world:

- Maximiliano Garcez, a labor rights lawyer who describes workers’ efforts to seek justice following a deadly mining accident in Brazil.

- Adriana Paz, an advocate with the International Domestic Workers Federation who understands firsthand the power of unions in ensuring domestic workers have safe, decent jobs.

- International Trade Union Confederation President Ayuba Wabba, who explores the Nigerian labor movement’s response to the COVID crisis on workers, and discusses the global labor movement’s plans to build back better for workers around the world.

- Preeda, a migrant worker rights activist in Thailand working with unions to help migrant workers meet the challenges of COVID-19.

- Sergey Antusevich, a brave union leader in Belarus working for democratic freedom in a repressive regime.

- Francia Blanco, a domestic worker and trans rights activist reaching marginalized workers through her all-trans domestic workers union.

These front-line leaders will share the steps they are taking to shape their livelihoods at the workplace and in their communities in the face of escalating attacks on democracy and civil rights, and explore how they seek to build a more equitable future, one inclusive of all workers as the COVID-19 pandemic upends structures, systems and societies.

‘Tears of Joy’

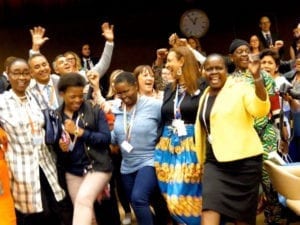

Union activists celebrate after the ILO adopts Convention 190 to end gender-based violence at work. Credit: ITUC

In the first episode, Modise shares how she and women unionists around the world campaigned for adoption of an International Labor Organization convention (regulation) on ending gender-based violence and harassment in the world of work, and how they are moving forward the campaign by pushing their governments to ratify Convention 190.

“We need to put more effort as the women in South Africa to make sure that whatever that you have were fought for is going to be realized in South Africa and be incorporated into our own legislation and make sure that it is implemented. We should not only have beautiful legislation, but we should have implementable legislation that we can be able to monitor and evaluate.”

As Modise heard an audio clip of women unionists singing and clapping the moment Convention 190 was adopted in 2019, she reflected on her experience.

“It was a breathtaking moment. We all shed tears. It was tears of joy because remember, when you went into that room as workers of the world, we knew what we wanted, but we didn’t know if the business constituents of the world understand where we are coming from.

“It really feels great, even though the bigger work has not yet started. We really want South Africa to ratify the convention. The work is not going to be ending at ratification. It’s also going to go in terms of after ratification, what next, and that’s where the bigger role and our activism is going to be needed.”

This podcast was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement No.AID-OAA-L-16-00001 and the opinions expressed herein are those of the participant(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID/USG.

The Solidarity Center Podcast’s seven-episode season will feature worker advocates from around the world:

The Solidarity Center Podcast’s seven-episode season will feature worker advocates from around the world: