Jul 27, 2017

The Mexican domestic workers union, SINACTRAHO, last week launched a far-reaching campaign to ensure domestic workers across Mexico are covered by employment contracts.

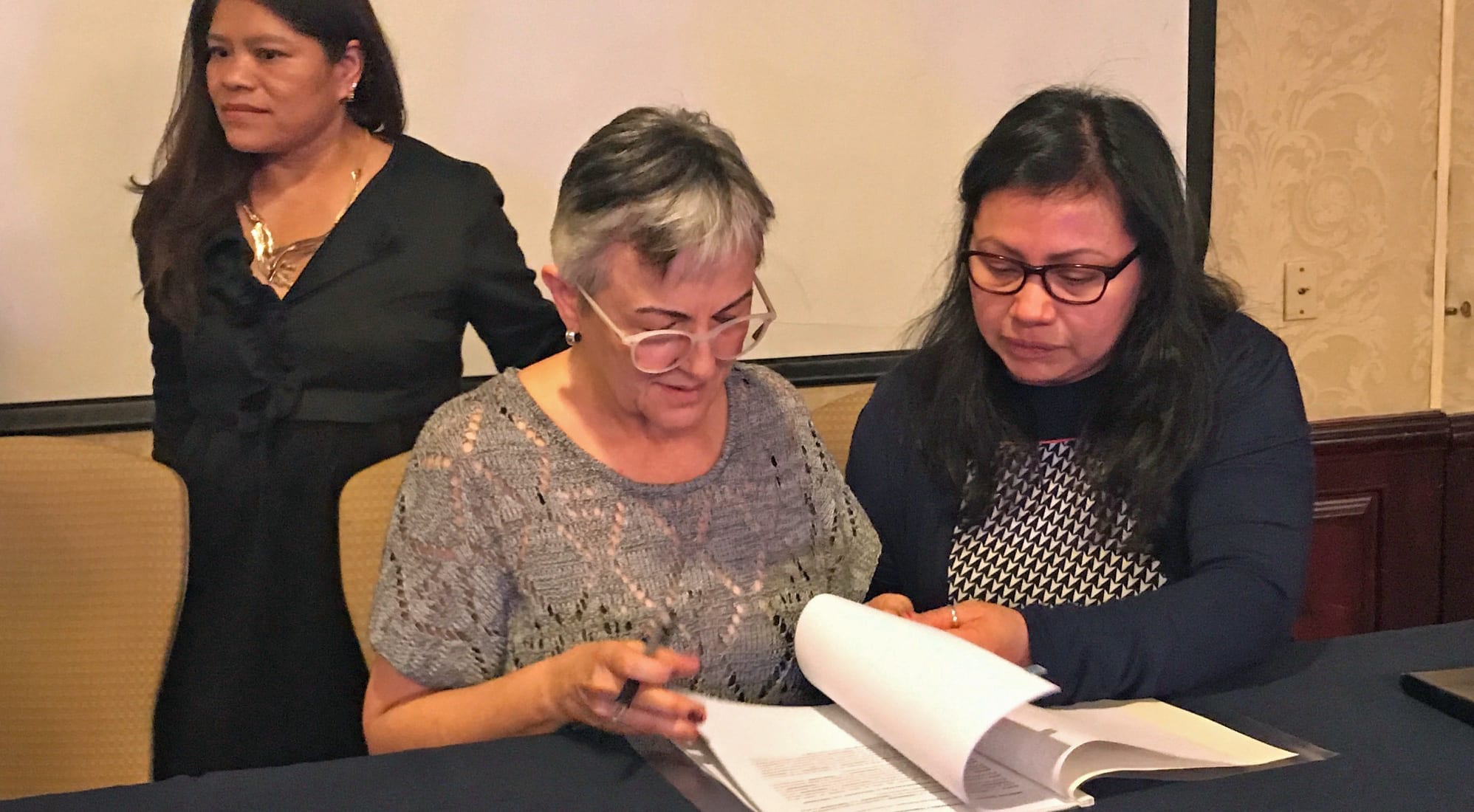

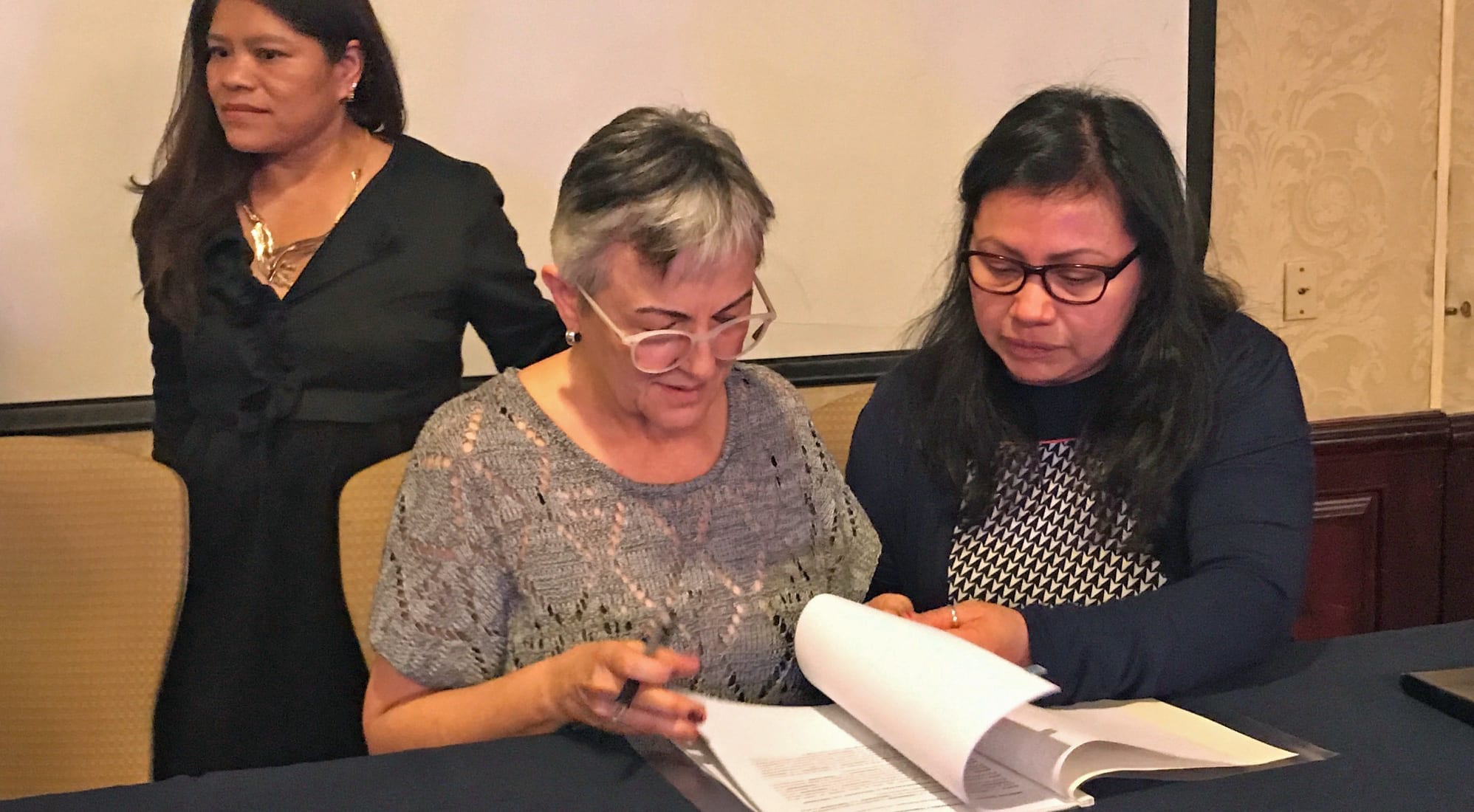

“Our goal is to have 10,000 workers sign a formal contract with their employers, in time for December holidays,” says Marcelina Bautista, SINACTRAHO co-president.

“Trabajo Digno por Ti, por Mi y todas Mis Compañeras” (“Decent Work for You, for Me, and all My Sisters”) also is gaining unlikely support—from employers.

“This is not an act of kindess, this is an action of responsibility,” says Maite Azuela, speaking on behalf of “Hogar Justo Hogar” (Home, Just Home), a group of employers that aims to work jointly with workers to improve rights and labor conditions.

“The unjust conditions that exist in our country and in our workplaces, we as employers too often replicate at home,” she says. “Building the country that we truly want is work that begins at home.”

During the campaign launch June 23, which coincided with Mexico’s annual day to celebrate domestic work, the union presented two model contracts, one for domestic workers who labor full time for an employer, and another for part-time workers. The contracts include a calculation sheet to determine proper accrual and payment of benefits afforded to workers under law.

“I appreciate Marcelina´s work and support, and all the people here, because I am beginning to understand that there are people who support us,” says SINACTRAHO member Yazmin Méndez.

“I know that we can change the situation that we as workers live. Our work is the same as another job, we have rights and resposibilities.”

SINACTRAHO was founded two years ago and has since grown to some 900 members nationwide. The struggle by Mexico’s domestic workers for rights on the job is documented in the film, “Day Off” (Día de Descanso), in which SINACTRAHO executive board members take part.

Mar 21, 2017

Dozens of day-labor farm workers (jornaleros) demanded improved wages, democratic representation, an end to sexual harassment and access to clean water as they marched across Mexico in a national caravan, “Fair Wages and Dignified Life.”

A proposed new law would make it much harder for farm workers to get compensation for job injuries. Credit: Solidarity Center/Gladys Cisneros

The workers, who left Baja California March 4 and arrived in Mexico City on March 17, sought to raise renewed awareness of their struggle for decent working conditions in the San Quintin Valley and hold employers accountable for their failure to uphold agreements reached in 2015. Although the settlement negotiated in 2015 included raising day wages to between 150 and 180 pesos (approximately $7 to $9), these wage levels have been unevenly applied.

“We are here to demand the same things we have been asking for, for two years,” says Lorenzo Rodriguez, general secretary of the SINDJA union.

Following the 2015 jornaleros strike, workers formed a national independent union that has grown to include farm workers from four Mexican states. Registering their independent union, SINDJA, is the only demand that has been met so far, say union leaders. Workers negotiated the agreement with the government, but the agribusiness owners and growers must comply.

“We don’t even have the right to live,” says farm worker leader Bonifacio Martinez. “And with proposed new government reforms, we are forbidden to get sick at work,” he adds, referring to proposed legislation that would place government and employers, not medical professionals, in charge of determining whether an injury is work-related.

A 2015 Los Angeles Times series found many workers on export-oriented farms “essentially trapped for months at a time in rat-infested camps, often without beds and sometimes without functioning toilets or a reliable water supply.”

The national caravan included families of the 43 disappeared students of Ayotzinapa, who continue to seek answers and justice. The march coincided with the two-year anniversary of a historic 12-week strike and popular mobilization in the San Quintin Valley.

Jan 6, 2016

Whether building a towering office building in downtown Zimbabwe, sewing garments in a Bangladesh factory or digging for phosphate in Mexico mines, the world’s unsung working people demonstrate, time and again, the dignity of work. Here, we celebrate some of the amazing women and men we partnered with in 2015, and showcase their efforts to improve their lives and livelihoods and tip the scales toward greater equality in their countries.

As Mervat Jumhawi, a former garment worker and union organizer working with the Solidarity Center in Jordan, described her own experience: “When I became member of the union, I became stronger.”

[portfolio_slideshow id=6893]

Sep 11, 2015

Dozens of union members and their allies from across Mexico gathered today to celebrate the official launch of the country’s first domestic workers’ union, SINACTRAHO. The union’s formation culminated a 15-year struggle for rights on the job by those whose work often goes unrecognized, and today’s events marked the union filing for official government recognition.

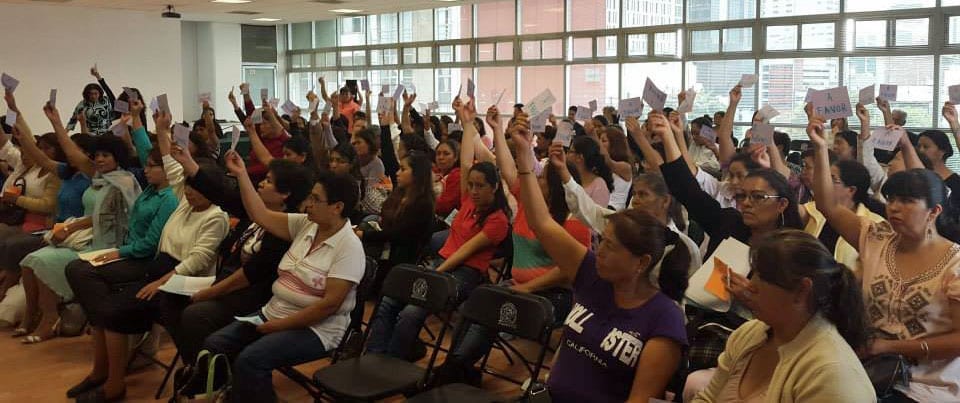

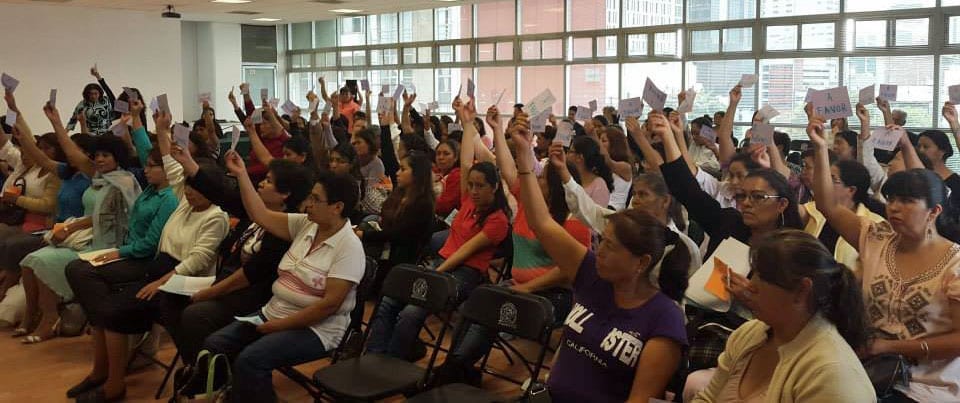

Earlier this week, the National Union of Workers (UNT) approved SINACTRAHO’s affiliation. Domestic workers from states like Colima, Chiapas, Puebla, Guerrero, Mexico City and elsewhere around the country voted to form the union and elected an executive committee earlier in August.

“I am very excited for today because it is a historical victory for the domestic workers in Mexico,” says Isidra, a domestic worker who took part in today’s events. “From now on, we will have rights and no one will be able to take them away from us. Our rights will be respected, no more low salaries and disrespectful treatment. Our work is valuable.”

Domestic workers cast their vote on whether to form a union. Credit: CACEH

“This union was created to make the difference for domestic workers in this country. It is an historic moment for the more than 2 million domestic workers in Mexico,” says Marcelina Bautista, a former domestic worker who founded the Center for Support and Training of Domestic Workers (CACEH). CACEH’s outreach efforts among domestic workers led to the formation of SINACTRAHO, which launches with 60 members and plans to continue reaching out to domestic workers across the country.

Domestic Workers’ Union: A Dream Come True

The struggle by Mexico’s domestic workers for rights on the job is documented in the film, “Day Off” (Día de Descanso), which premiered yesterday, with SINACTRAHO executive board members taking part. Elizabeth Tang, general secretary of the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) and Jill Shenker, IDWF North America Regional Coordinator and international organizing director for the U.S.-based National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA) also joined the event.

Bautista says when CACEH was formed 15 years ago, she dreamed of creating a trade union, but the conditions were not favorable. “Today that dream will come true,” she says. Bautista is the IDWF regional coordinator for Latin America and from 2006 to 2012, served as general secretary of CONLACTRAHO, the confederation of Latin American and Caribbean domestic workers.

“Through this struggle, we’ve come to realize that we’re wise.”

Domestic workers celebrate with a green glove, the campaign’s symbol of rights and respect on the job. Credit: Adriana Paz

Domestic Workers Raising Awareness among Public, Lawmakers

In addition to organizing domestic workers, CACEH conducts training and education programs, with train-the-trainer workshops expanding CACEH’s network of domestic workers. CACEH has taken part in labor legislation advocacy at multiple levels of government and has spearheaded campaigns to raise public awareness about the value of domestic work and the rights of domestic workers.

“All the positioning work has been very successful, and today the Senate and Congress are aware of the issue,” Bautista says.

Going forward, domestic workers will ramp up efforts to push Mexico to ratify the International Labor Organization Convention (ILO) Convention 189 covering domestic workers.

“We didn’t know how to shout the first time we went on a march,” Bautista says. “Now they listen to us!”

Aug 4, 2015

More than 300,000 domestic workers in Hong Kong, Special Administrative Region of China have migrated from the Philippines, Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries seeking jobs to support their families. Recent high-profile instances of employer abuse against these domestic workers—unpaid wages, 24/7 working hours, and even physical assault—offer a glimpse into the migrant crisis that recently has focused the world’s attention on longstanding issues of debt bondage, human trafficking and mistreatment of workers striving to earn a decent living in the region.

But when they face an abusive work situation in Hong Kong, SAR, migrant domestic workers—nearly all of whom are women—have an opportunity for strong support through the Federation of Asian Domestic Workers Union (FADWU).

“We help them file a case with the Labor Department because, as a union, we can have the right of representation in a tribunal,” says Leo Tang, organizing secretary for the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU), which includes FADWU as an affiliate. “Sometimes we provide shelter to those in need.”

Solidarity Center Labor Migration Conference

Tang is among more than 200 migrant worker rights experts taking part in the Solidarity Center’s Labor Migration conference in Indonesia, August 10–12. Conference participants will strategize within themes that focus on labor recruitment reform; organizing; and migrant worker access to justice.

Assisting workers first requires reaching out to them before they need support. That’s why organizing domestic workers is fundamental for the five unions that comprise FADWU. Based on nationality, the unions provide a cultural meeting ground that extends to education and training about their rights on the job.

Tang now is taking the members to the next step: shaping an inclusive union. “We are trying to unite all nationalities, all the migrants, under the federation structure,” he says.

In Mexico, where 10 percent of domestic workers migrate from countries such as Honduras and Peru, the Center of Support and Training for Domestic Workers (CACEH), reaches out to these workers to educate them about their rights.

“They have no information,” says CACEH leader Marcelina Bautista. “Often what happens is that their employer starts to retain their salaries to pay back the air ticket cost (the employer) spent bringing them to Mexico,” she said, speaking through a translator. Bautista, who also serves as International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) regional coordinator for Latin America, also will share her insights at the Solidarity Center event, “Labor Migration: Who Benefits? A Global Conference on Worker Rights and Shared Prosperity

CACEH, which Bautista founded 15 years ago, now has an extensive word-of-mouth network that enables them to organize domestic workers. CACEH also provides education services and train-the- trainer workshops that further expand the organization’s connection with domestic workers.

Market Vendors Join Forces to Improve Their Lives

In the Dominican Republic, where 60 percent of the workforce labors in the informal economy, Pablo de los Santos, president of National Federation of Sellers and Market Workers, says organizing market sellers involves letting them know about the disadvantages they face as self-employed individuals.

“I tell them about the advantages they could have once they organize themselves: better working conditions, living conditions, better benefits, for themselves and their families,” he said, speaking through a translator. Up to 60 percent of informal workers in the Dominican Republic are migrant workers, primarily from Haiti.

The organization, which started out in 2007 with a pilot program and now has branches in all 32 states, has sufficient bargaining power that it convinced banks to give 1 percent loans to dozens of informal economy workers, an achievement individual sellers often unattainable. The federation also negotiated improved infrastructure in Santo Domingo’s bustling open markets, and is seeking more space for Haitian workers.

Like Santos, Bautista is looking forward to taking part in the Solidarity Center labor migration conference to improve the ability of her organization to help workers. “It is very important to learn from the experience of all the other domestic workers who work in migration, especially colleagues who work in Asia and the United States, because they have a lot of experience working with migrant workers,” she says.

Follow Labor Migration: Who Benefits? at the Solidarity Center website and on Twitter @SolidarityCntr.