Nov 20, 2019

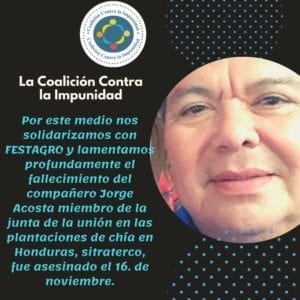

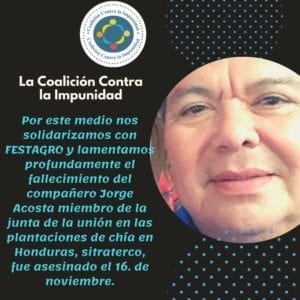

The international human rights community is condemning the murder on Saturday of Jorge Alberto Acosta, executive member of the Workers’ Union of the Tela Railroad Company (SITRATERCO) and president of the union’s Savings and Credit Cooperative section.

Acosta’s murder comes just three weeks after the kidnapping and torture of Jaime Rodríguez, former president of the Union of Middle School Teachers (COPEMH).

The assassination follows more than a year of death threats that Acosta documented with the Anti-Union Violence Network in Honduras. According the Network, Acosta said he was informed by the Honduras’ National Anti-Extortion Force (FNA) on April 14, 2018, that three people had set up an operation near his house to plan his execution. Previously, FNA informed him of the capture of an alleged gang member who confessed there was a plan to kill him.

In May 2018, the Honduran state issued protective measures for Acosta due to the risks he faced for his human rights activity. Physical assaults, death threats, surveillance, attacks and burglaries against other union officers also have been documented and reported.

During 2018, the SITRATERCO Executive Committee sought out the Honduran government’s relevant law enforcement and human rights agencies to denounce a series of systematic acts of anti-union violence directly related to their work.

‘The Government Must Protect Threatened Union Leaders’

Following Acosta’s murder, the Coordinating Body of Latin American Agricultural unions (COLSIBA) echoed calls by Honduran unions that the state provide real, robust protection to Acosta’s family and SITRATERCO leadership and seriously undertake the protection of all threatened unionists currently authorized protective measures.

Following Acosta’s murder, the Coordinating Body of Latin American Agricultural unions (COLSIBA) echoed calls by Honduran unions that the state provide real, robust protection to Acosta’s family and SITRATERCO leadership and seriously undertake the protection of all threatened unionists currently authorized protective measures.

In a statement, four members of the U.S. Congress condemned the murder and said the Honduran government must thoroughly investigate and prosecute the assassination.

“The labor movement of Honduras is in more danger than ever. Yet the Honduran government fails to provide the legally mandated protection systems, does not investigate or prosecute those who threaten or kill union activists, and utterly fails to enforce its own labor laws,” the lawmakers said in the statement. “As the AFL-CIO and Honduran unions have documented, the government of Honduras has failed to comply with its legally mandated obligations under the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) to prevent anti-union violence, among other rampant violations.”

The agricultural worker federation FESTAGRO and its affiliated unions joined the call to demand justice for Acosta, #JusticiaparaJorge. The agricultural unions, whose members have been threatened, attacked and murdered in recent years for their efforts to seek basic rights on the job, urged the government to protect threatened rights activists.

“We demand immediate protection of the leaders from various unions who fight to improve the living conditions of the Honduran population and mainly in the agricultural sector, where violence is more marked and continuous. According to the report of the Network Against Anti-union Violence, more than 70 percent of attacks occur in this sector,” FESTAGRO, a longtime Solidarity Center partner, said in a statement.

In August, 55 members of Congress sent a letter to the U.S. Trade Representative and the Acting Secretary of Labor citing ongoing labor and human rights violations, including anti-union violence and threats at Honduran plantations as repeated violations of the CAFTA labor chapter. For example, workers’ efforts to form unions affiliated to FESTAGRO have been violently repressed. SITRATERCO, the union that founded the Honduran labor movement, is also a founding member of the FESTAGRO federation.

In 2012, the AFL-CIO and 26 Honduran unions and civil society organizations filed a complaint under CAFTA’s labor chapter. The complaint, filed with the Labor Department’s Office of Trade and Labor Affairs, alleges the Honduran government failed to enforce worker rights under its labor laws. In a February 2015 report, and again in October 2018, the U.S. Trade and Labor Affairs office documented that the Honduran government demonstrated no progress on emblematic cases or systematic rights violations.

Nov 4, 2019

Since the start of 2019, more than 2,000 migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan have joined together to protect their rights abroad through the new Migrant Workers’ Union. On October 17, more than 100 union delegates came together in the town of Isfana, Kyrgyzstan, for the union’s founding congress.

Newly elected deputy chairwoman of the Migrant Workers’ Union, Batyrova Kanykey, addresses more than 100 delegates at their founding congress. Credit: Elena Rubtsova

The congress marks a crucial step as the union establishes itself as a leading support system for migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan. Delegates cast their votes to elect union leadership and planned activities and outreach to more workers in the coming year.

Workers from across three regions of western Kyrgyzstan—Batken, Jalal-Abad and Osh—worked together to build this new organization, with support from the Solidarity Center and Insan-Leilek, a local foundation that provided assistance to migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan over the last five years. The union has also garnered support from the Germany-based Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung and Caritas France.

Insan-Leilek celebrated the milestone with a video in Russian.

Protecting Workers Abroad

Migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan, and from around the world, often face discrimination, exploitation and unsafe working conditions when they arrive in their destination countries. In Russia, a common destination for Kyrgyz migrants, workers have reported working without official contracts or having their wages stolen, with few opportunities to stand up for their rights and hold their employers accountable. Kyrgyz workers also travel to Kazakhstan, Germany and elsewhere for work. Many stay year-round, while others travel back and forth each year for seasonal jobs.

“A large number of labor migrants are subjected to exploitation and violation of their rights by employers, employment agencies and other intermediaries,” says Gulnara Derbisheva, a human rights activist in Kyrgyzstan and the leader of Insan-Leilek. “They face abuse of authority by the police and other officials. In some cases, labor migrants are victims of trafficking and forced labor.”

Since 2015, the Solidarity Center and Insan-Leilek have held pre-departure trainings for working women and men who are preparing to migrate abroad, most of them to Russia. Through these trainings, thousands of migrants have learned about their rights and the protections they have under Russian labor law. Armed with this knowledge, many workers have started exercising their rights the moment they arrive at their new jobs.

Many migrants have used their knowledge of Russian labor law to negotiate higher wages and overtime pay. Others have worked with their employers to ensure they have fully signed contracts that specify their working conditions and document their ability to work in the country. Migrant women have also learned how to protect their rights, including avoiding human traffickers and reporting workplace harassment.

The Solidarity Center also provides training participants with contact information for local legal support in their destination countries. Through hotlines and free consultations, workers can seek legal help if or when they encounter issues on the job, such as wage theft and harassment.

The Solidarity Center’s pre-departure trainings have also shown migrants how they can join trade unions to further protect their rights, even when they are working abroad. As a result, workers decided they should create their own union so they could tailor it to support Kyrgyz migrants.

Migrant Workers Organizing for Justice

The creation of the Migrant Workers’ Union, its members say, is not just timely but also necessary to protect their rights at a time when more than one-fifth of Kyrgyz citizens are living and working abroad.

Gulzat, a delegate at the congress from the village of Boz-Adyr in the Batken region, first heard about the union at a training session the Solidarity Center and Insan-Leilek held in her village earlier in 2019. “I learned many important things about my labor rights and how they could be protected,” she says. “It was then that I decided to join the Migrant Workers’ Union because I am going back to work in Russia.”

Gulzat first went to work in Russia in 2010, where she experienced wage theft firsthand. “I became a dishwasher in a Moscow cafe and was a victim of fraud when I was left without a salary,” she explains. “I didn’t know where to turn for help, but now I know.”

The Migrant Workers’ Union currently has 2,150 members. But the union’s protections extend beyond just its members. Migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan rely on decent wages not only for themselves but also to support their families back home. Migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan remitted an estimated $2.48 billion in 2018, about 34 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. Since 2017, Kyrgyzstan has been the most remittance-dependent country in the world, and remittances are particularly important in its western regions like Batken. As migrant workers learn to defend their rights abroad, they also ensure their families in Kyrgyzstan can have more economic security and access more opportunities at home.

“Everybody needs their union,” says Gulzat. “Especially migrants.”

Feb 14, 2019

Tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers waged weeks-long strikes in December and January to protest low wages and unequal pay increases—and now workers say factory employers are using the walkouts to further repress their efforts to form unions and collectively bargain better wages and working conditions.

More than 11,000 garment workers have lost their jobs or faced repression as a result of the wage protests, and employers and the police have filed cases against more than 3,000 workers, according to the global union IndustriALL. Many workers fired say they were not involved in the protests.

During the walkouts, police used tear gas, water cannons, batons and rubber bullets, reportedly injuring dozens of workers and killing 22-year-old Sumon Mia, a worker at Anlima Textile in Savar, who was shot dead on his way back to work from lunch.

Billboards with names and photographs of terminated workers have been posted at some factories as an intimidation tactic, and union leaders say factory management is exploiting the walkouts to target and blacklist them from employment in the sector.

Factory walkouts began the second week of December, when mostly nonunion garment workers from roughly 350 factories in Gazipur, Ashulia and Narayanganj protested the elimination of the 5 percent annual wage increase for 2018 and a basic wage increase applied unequally to workers with various skill levels.

Recent Repression of Worker Rights Part of Longer Trend

Following the deaths of more than 1,200 garment workers in the 2012 fire at the Tazreen Fashions factory and the 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse, workers vigorously organized to form unions and negotiate contracts, as the Bangladesh government and ready-made garment (RMG) employers responded to international pressure to improve safety and wages.

But in recent years, employer harassment—including physical attacks and threatening home visits—and government resistance to workers seeking to register unions have meant even fewer workers can join together to collectively improve their workplaces. As recently as November 2018, two union organizers were brutally attacked by men associated with factory management, according to union leaders.

At the same time, Bangladesh’s highest court threatens the expulsion of the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh established after the Rana Plaza disaster. The legally binding agreement between hundreds of primarily European corporate retail brands and unions conducted safety inspections at more than 1,000 factories and educated workers on safety and other workplace rights.

Bangladesh is the biggest producer of garments in the world after China, with apparel exports totaling more than $30 billion last fiscal year. Although the Bangladesh RMG industry is by far the country’s biggest export earner, wages remain the lowest among major garment-manufacturing nations. Yet the cost of living in Dhaka is equivalent to that of Montreal.

Feb 7, 2019

Although the government of Uzbekistan has made progress on ending child and adult forced labor in the cotton fields after more than a decade of international pressure, a new report finds that forced labor remains rampant in other arenas of Uzbek life, affecting public-sector workers in particular. This practice undermines the quality of public services and depletes workers’ earnings, as they must bear the costs of their own forced labor.

The report, “There Is No Work We Haven’t Done: Forced Labor of Public-Sector Employees in Uzbekistan,” released today by the Solidarity Center and Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights (UGF), outlines the devastating toll forced labor has on workers and essential public services, particularly in health care and education, where trained specialists are taken out of work for hours, days or even weeks to perform manual labor at the whim of officials.

Last March, 23-year-old teacher Diana Enikeeva was struck and killed by a truck while she and other teachers were cleaning the highway in the Samarkand region in preparation for a visit by Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev. According to the report, although Enikeeva’s death raised a public outcry in popular and social media, prompting the president to order officials to stop using public-sector employees and students for “public” work such as street cleaning in May 2018, the work was not out of the ordinary for public-sector employees, including teachers, and did not stop.

Interviews conducted by a team of UGF monitors in nine regions in Uzbekistan over two months in spring 2018 with public employees and others affected by forced labor revealed that government officials were using public-sector employees under threat of penalty as a constant source of labor and funds to fulfill local needs or centrally imposed mandates. Some workers reported that their unions—which are weak and subordinate to government and/or employers—sometimes assisted in organizing or directing their forced labor.

Public-sector workers, among the lowest-paid professionals in the country, reported that they were forced to provide manual labor for community maintenance and beautification, street cleaning, wheat harvesting and collection of scrap metal and paper. Teachers, health care workers and employees of state agencies said they were routinely sent to clean streets, plant flowers, do construction work, dredge ditches and perform public maintenance for hours or days every week, without extra pay. Under the community maintenance program “Obod Kishlok” [Well-Maintained Village], announced by the president in March 2018, local officials forced public employees to bear full responsibility for repairing, painting and gardening, even at private houses. Workers reported often paying for costs associated with forced labor, including for food and transportation to forced labor assignments as well as for construction supplies, tools and flowers and seedlings for planting. Several children and farmers also reported that children and teachers were taken out of class to harvest silk cocoons under threat of penalty.

“Given that forced labor continues in Uzbekistan, even after the president and some other government officials have publicly condemned it, authorities must urgently and immediately address the systemic root causes of forced labor—the lack of independent and representative labor unions, absence of effective complaint and accountability mechanisms, rampant corruption, lack of accountability of local authorities, centrally imposed mandates and a punitive and exploitative agricultural system,” said Abby McGill, senior program officer for Eastern Europe and Central Asia at the Solidarity Center.

Read the report in Russian and Uzbek.

Dec 13, 2018

Worker rights advocate Apantree Charoensak, vice chair of the Thai Labor Solidarity Committee, Women’s Division, was honored this week for her work protecting and promoting human rights by Thailand’s National Human Rights Commission (NHRC).

Courtesy Apantree Charoensak

Charoensak led the successful 2017 struggle for collective bargaining rights for collective bargaining rights for fast food workers at one of Thailand’s largest KFC franchises, in which 3,100 workers won a contract that includes an early retirement program, 23 meals provided by the company per year and motorcycle maintenance funds for delivery workers. The workers are among 2,400 members represented by the Cuisine and Service Workers’ Union, a Solidarity Center partner and IUF affiliate.

“I am proud to have advocated for human rights for the past seven years,” Charoensak said in a statement on the award, granted to 13 human rights defenders as part of International Human Rights Day December 10.

Charoensak has been leading the struggle for fast food workers across Thailand for nearly a decade. During negotiations at KFC, she was fired from her position at Yum! Thailand, which operates some of the KFC franchises.

As a manager at the corporation where she supervised up to a dozen restaurants, Charoensak says she began union organizing to rectify what she saw as a large pay disparity between front-line workers and managers. Ultimately two unions formed, one covering front-line employees and one for supervisors. Over the years, she says management also tried to end her union activism by offering her large sums of money, which she refused, and isolated her at work, giving her little to do—time she filled by completing a master’s degree in political science and addressing union members’ concerns.

Following Acosta’s murder, the Coordinating Body of Latin American Agricultural unions (COLSIBA) echoed calls by Honduran unions that the state provide real, robust protection to Acosta’s family and SITRATERCO leadership and seriously undertake the protection of all threatened unionists currently authorized protective measures.

Following Acosta’s murder, the Coordinating Body of Latin American Agricultural unions (COLSIBA) echoed calls by Honduran unions that the state provide real, robust protection to Acosta’s family and SITRATERCO leadership and seriously undertake the protection of all threatened unionists currently authorized protective measures.