Apr 28, 2021

Women working in South African mines “at times confront danger, violence and indignity in their work environments,” where gender-based violence and harassment (GBVH) appears both widespread and normalized, according to a new report from the Solidarity Center and South Africa-based Lawyers for Human Rights (LHR).

The report, “What Happens Underground Stays Underground: A Study of Experiences of Gender-Based Violence and Sexual Harassment of Women Workers in the South African Mining Industry,” found that while verbal harassment is most common, women mineworkers also face requests for sexual favors in exchange for physical labor or for promotions, transfers or changes in work schedules. And sexual assault and harassment can occur both above and below ground at mines.

GBVH in the mining sector can be attributed to a range of complex political, social and economic factors, including:

- The dark and isolated nature of underground mines makes GBVH more likely, and monitoring and supervision of workers and evidence collection more difficult.

- South Africa’s dominant patriarchal social norms are exacerbating reporting barriers by enabling a culture of silence and victimization and the economic dependency of women on men.

- Women working within the numerically and culturally male-dominated sector are outnumbered and often subordinated in their personal security and professional development.

- Some business strategies are undermining the well-being of women workers in the mining industry, such as the outsourcing of female worker recruitment, which can expose recruits to sexual exploitation by gatekeepers of lucrative jobs, and the failure to accommodate women in the design and placement of facilities such as bathrooms, locker rooms, bus stops and elevators, which leaves women vulnerable to violence and harassment.

The report’s findings and recommendations are based on interviews conducted in Cape Town, Johannesburg, KwaZulu-Natal, Mpumalanga, Rustenburg and Wonderkop last year with former and current women mineworkers and representatives of women’s structures within mining unions, including the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), the Center for Applied Legal Studies at Wits (CALS), the South African Gender Equality Commission, the South African Human Rights Commission and the Wits Mining Institute. All women mineworker interviewees chose to remain anonymous, to protect their safety and jobs.

“Women mineworkers, striving to support their families, live a troubling reality—one that comes at great cost to their physical and mental well-being. The stakes are high, and the failure to prevent GBVH amounts to granting tacit permission to perpetrators,” according to the report.

Lead report researcher Sheila B. Keetharuth—who previously served on the United Nations team of international experts on the Kasai, Democratic Republic of Congo—says that the lower proportion of female workers in the mining sector in South Africa is, “a recipe for disaster that necessitates easily accessible and trustworthy reporting mechanisms as provided for in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.”

The International Labor Organization two years ago adopted Convention 190, the first global binding treaty to address GBVH in the world of work. The treaty calls on governments, employers and unions to work together to confront the root causes of GBVH, including the multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination, gender stereotypes and unequal gender-based power relationships. South Africa has yet to ratify Convention 190.

“Safe and healthy jobs are among workers’ most fundamental rights,” says Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau. “As we observe World Day for Safety and Health at Work today, we must continue to reinforce that a safe workplace is one that is free of gender-based violence and harassment. And through unions, workers can achieve the strong, collective voice needed to improve safety and health on the job.”

Report recommendations include that:

- South Africa immediately ratify ILO C190 on Violence and Harassment at Work

- Occupational health and safety laws and policies, as well as sector-specific laws and policies, obligate employers to prevent and eliminate GBVH

- The country’s Mining Charter extend employer obligations with respect to prevention and elimination of GBVH and require that special measures be adopted for women working in mining

- In consultation with workers and unions, compulsory GBVH risk assessments be established for identifying safety risks.

- Acquisition of a mining license be conditioned on right holders’ commitment to the prevention and elimination of GBVH

- Employers adopt confidential and independent reporting system

- Women working underground be provided with a confidential, anonymous, efficient and easily accessible incident reporting system.

- Workers be informed that victims of sexual assault have the right to press separate criminal or civil charges against their perpetrators.

- Mandatory and effective education and training with respect to laws and policies on GBVH be provided to workers and supervisors, and that policies addressing GBVH be printed in all official languages, displayed conspicuously throughout the mining shafts, and widely and regularly promoted through interactive workshops.

- Policies against GBVH be included in employment contracts and clearly state repercussions for GBVH violations.

- The mining industry provide education and counseling to rehabilitate perpetrators in cases not likely to reach the level of criminal prosecution.

“Although the report shows that GBVH is rooted in complex and deeply entrenched patriarchal social norms, it also presents fairly simple, cost-effective changes to the work environment—such as improved lighting, a buddy system and safer toilet and locker room locations—that will make women mine workers less vulnerable to crimes of opportunity,” says Solidarity Center Rule of Law Department Senior Program Officer Ziona Tanzer.

Beginning in 2014, the Solidarity Center was a core member of a global coalition of worker rights organizations led by women union activists that successfully advocated for Convention 190. We support our partners as they campaign for their governments to ratify ILO Convention 190 and recognize GBVH as a primary barrier to achieving gender equality and a key step for security of all workers’ rights and seek to enhance the voice of women and other marginalized workers in policy making at the local, national, and international levels to reduce the risk of gender-based violence at work—including through their unions.

Apr 21, 2020

In Tunisia, 150 women garment workers self-quarantined in their factory to manufacture desperately needed protective masks, churning out 50,000 a day as the COVID-19 crisis broke out. The South African Clothing and Textile Workers’ Union (SACTWU) reached an agreement with employers to guarantee six weeks full pay for 80,000 workers, nearly all women, as operations shut down. And, undeterred by the limitations of social isolation policies, Honduran women union activists are using social media to demand their government ratify a global treaty (Convention 190) ending gender-based violence and harassment (GBVH).

Around the world, women and their unions are leading the way, recognizing that gendered economic challenges are worsened by the pandemic, which is hitting women and other marginalized groups especially hard. They are spearheading calls for safety and health protection and raising awareness about C190, which provides remedies and tools for governments and employers to address the increase in GBVH at work and home.

C190, which the International Labor Organization approved last year, requires employers and governments to take steps to address and prevent GBVH at home, both when it is a place of work and when domestic violence impacts workers’ workplace performance.

Challenging the View that Domestic Violence is a ‘Private Matter’

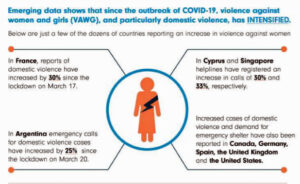

One of the most dramatic examples of how the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated gender inequalities is the significant increase in domestic violence against women.

In El Salvador, domestic violence has increased by 70 percent. Anti-domestic violence service providers from Lesotho to Brazil are reporting increases in calls from women experiencing abuse seeking assistance, according to Solidarity Center staff. Isolated in their homes—or the homes of their employer if they are domestic workers without access to private spaces—many women cannot even reach out for assistance or otherwise seek help to end the abuse.

COVID-19 also has engendered a brutal twist: Exposure to the coronavirus is being used as a threat to further control partners and family members, who in some cases are being forbidden from leaving the house or even are thrown out with nowhere to go. The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) and global unions such as UNI and IndustriAll offer resources and guidance about measures unions can take to address the increase in domestic violence resulting from COVID-19 lockdowns.

In Honduras, union activists are posting photos of themselves on social media with signs urging passage of C190. Credit: Promotoras LegalesUnions have long recognized domestic violence as a critical issue impacting a workers’ ability to obtain and maintain employment. Research shows that when workers are affected by domestic violence, it often affects their participation in work, their productivity and achievement of work tasks and targets. Employers often inadvertently blame and even terminate the target of domestic abuse in response to the disruptions caused by the abuser.

A Canadian Labor Congress (CLC) survey of more than 8,000 union members that found 67 percent had experienced domestic violence. Of those, 47 percent say they were prevented from going to work by their abuser and 8 percent lost their jobs because of ramifications from their abuse. Surveys by the ITUC in four countries found similar results. For instance, 75 percent of respondents in the Philippines reported that domestic violence affected their work performance because they were unwell, distracted or injured as a result. One in three respondents (34 percent) who had experienced domestic violence reported that their abuser was employed in the same workplace.

C190 prohibits violence and harassment, including GBVH in the “world of work,” which includes private and public places where work is performed, specifically recognizing that many workers work in their own homes or provide care or other services in others’ homes. C190 places responsibilities on ratifying governments, and in turn duties on employers, to mitigate the effects of domestic violence on workers’ ability to access and maintain employment.

In France, the General Confederation of Worker (CGT) is pushing the government to take action around the increase in domestic violence during the COVID-19 confinement by prohibiting dismissal of all targets of domestic violence and requiring employers to negotiate measures to prevent and protect targets of violence, including domestic violence.

Unions Address Effects of Domestic Violence on Workers

During the COVID-19 crisis, unions around the world are addressing the effects of domestic violence on workers.

During the COVID-19 crisis, unions around the world are addressing the effects of domestic violence on workers.

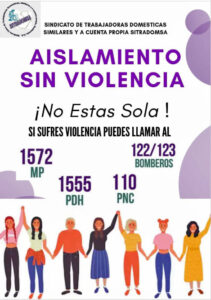

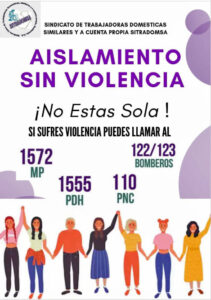

“Isolation without violence!” reads a graphic (at left) that the Guatemala domestic workers union, Sitradomsa, posted on its Facebook page, with contact information for those experiencing abuse.

In South Africa, where police have received more than 87,000 reports of domestic violence in the first week of mandated social isolation, the Federation of Unions of South Africa (FEDUSA) is appealing to the government to increase the number of mobile clinics, both for COVID-19 testing and for treating targets of gender-based violence with a special focus on vulnerable areas, such as densely populated townships and informal settlements. “The mobile clinics should include staff or other health workers specially trained in handling and managing gender-based violence, including providing psychological support for the victims,” the federation says in a statement.

In Georgia, after an employer forced workers to sleep at a grocery store overnight because of the country’s 9 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew, the Georgia Trade Union Confederation (GTUC) took action to ensure the workers, mostly women, could safely return home. The union successfully urged the government to require employers to provide workers free transport from work, an element taken from C190, which encompasses a broad definition of violence at work that includes the time workers spending getting to and from work.

Women’s groups in Lesotho and unions representing garment workers, nearly all of them women, are working with employers and the government to address the effects of domestic violence on workers during the lockdown as they continue to fight for wage replacements.

The global campaign for C190 ratification also continues, as the crisis brings in stark relief the connection between violence at home and work. “From home, we are still campaigning for the ratification of C190,” read signs dozens of union members and their families in Honduras are posting on Facebook from their homes.

In Nigeria, women leaders in the Nigerian Labor Congress are highlighting how C190 addresses the increased violence and harassment experienced by nurses, the majority of whom are women, and workers who are now forced to stay home in abusive homes. In South Africa, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and SACTUW are championing government ratification of C190 through Facebook and other online platforms.

“Protecting workers from domestic violence is a core part of an employers’ safety and health responsibilities and the ‘duty of care’ for their employees,” according to the Domestic Violence@Work Network. “It is also an opportunity to think beyond the immediate crisis so that social partners, including governments, employers, unions and service providers, are part of transformative change.”

‘We Can Emerge from this Crisis Stronger’

In the long run, the impact of COVID-19 will disproportionately affect women’s economic and productive lives differently than men, according to a new United Nations report. “Across the globe, women earn less, save less, hold less secure jobs, are more likely to be employed in the informal sector,” according to the report. “They have less access to social protections and are the majority of single-parent households. Their capacity to absorb economic shocks is therefore less than that of men.”

Women make up the majority of those on the frontlines of the pandemic—working as retail clerks, street vendors, domestic workers and health care workers, especially nurses, midwives and community health workers. Nearly 60 percent of women around the world work in the informal economy, where they are paid less with few or no social benefits and no reserves to fall back on in times of crisis. They often depend on public space and social interactions to make a living, and now are restricted to contain the spread of the pandemic. Globally, women make up 70 percent of the health workforce where they are literally face to face with the virus.

Women also are bearing the brunt of unpaid care work and housework at home, both of which have increased exponentially as families are isolated together, with children out of school and housebound elderly and ill relatives. Before COVID-19, women were doing three times as much unpaid care and domestic work as men. In Latin America, for instance, the value of unpaid work is estimated as between 15.2 percent (Ecuador) and 25.3 percent (Costa Rica) of GDP.

“The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted the need for women workers to be a part of negotiations with employers and governments and the need for continued leadership by women to bring an inclusive approach specifically with a focus on unpaid care work, domestic violence and equal pay,” says Solidarity Center Equality and Inclusion Co-Director Robin Runge.

The UN estimated earlier this year that based on current trends, it would take 257 years to close the gender gap in economic opportunity. Left unaddressed, the impact of the coronavirus will “compound global injustices and inequalities, further marginalizing women, people of color, migrants, informal economy workers, and other exploited groups,” according to the Women in Migration Network (WIMN), which includes the Solidarity Center. The alternative, WIMN says in a statement, is for the world to “emerge from this crisis stronger, more just and more equal.”

“To steer toward that brighter future, world leaders need to think big—and they need to listen to women. Given their many roles as providers, care givers, home keepers, and essential workers in both the formal and informal economy, women, including LGBTQI women, have a multilayered understanding of the impact of the crisis on family, community and work realities that clarifies the breadth and scale of response that is needed.”

During the COVID-19 crisis, unions around the world are addressing the effects of domestic violence on workers.

During the COVID-19 crisis, unions around the world are addressing the effects of domestic violence on workers.