Jan 18, 2019

At Cambodia’s iconic Angkor Archaeological Park in Siem Reap, trash collectors employed by the contractor V-Green are back on the job with a boost in pay this week after 200 workers waged weeks-long lunchtime protests for better wages, safer working conditions and improved social protections like health care.

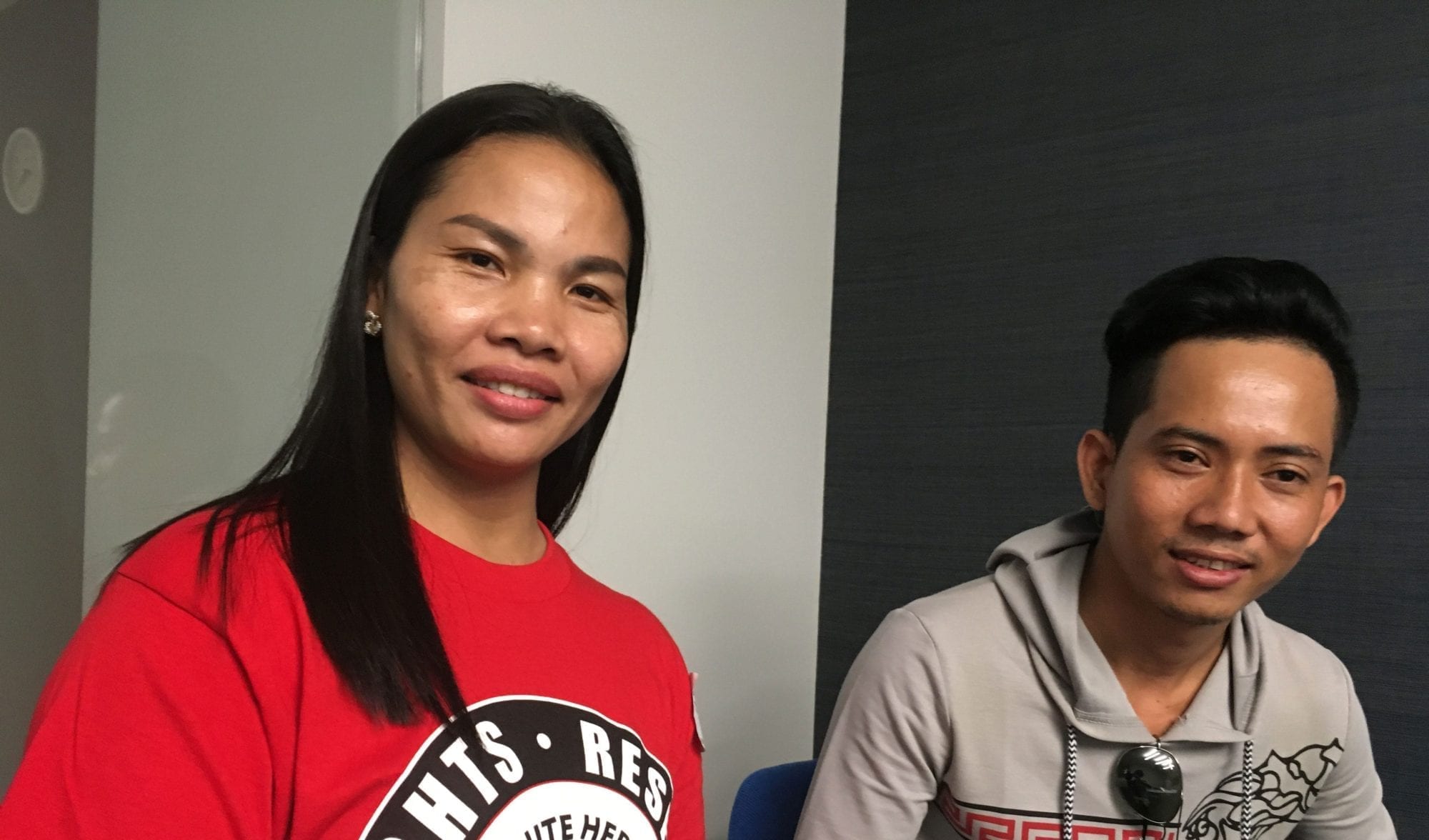

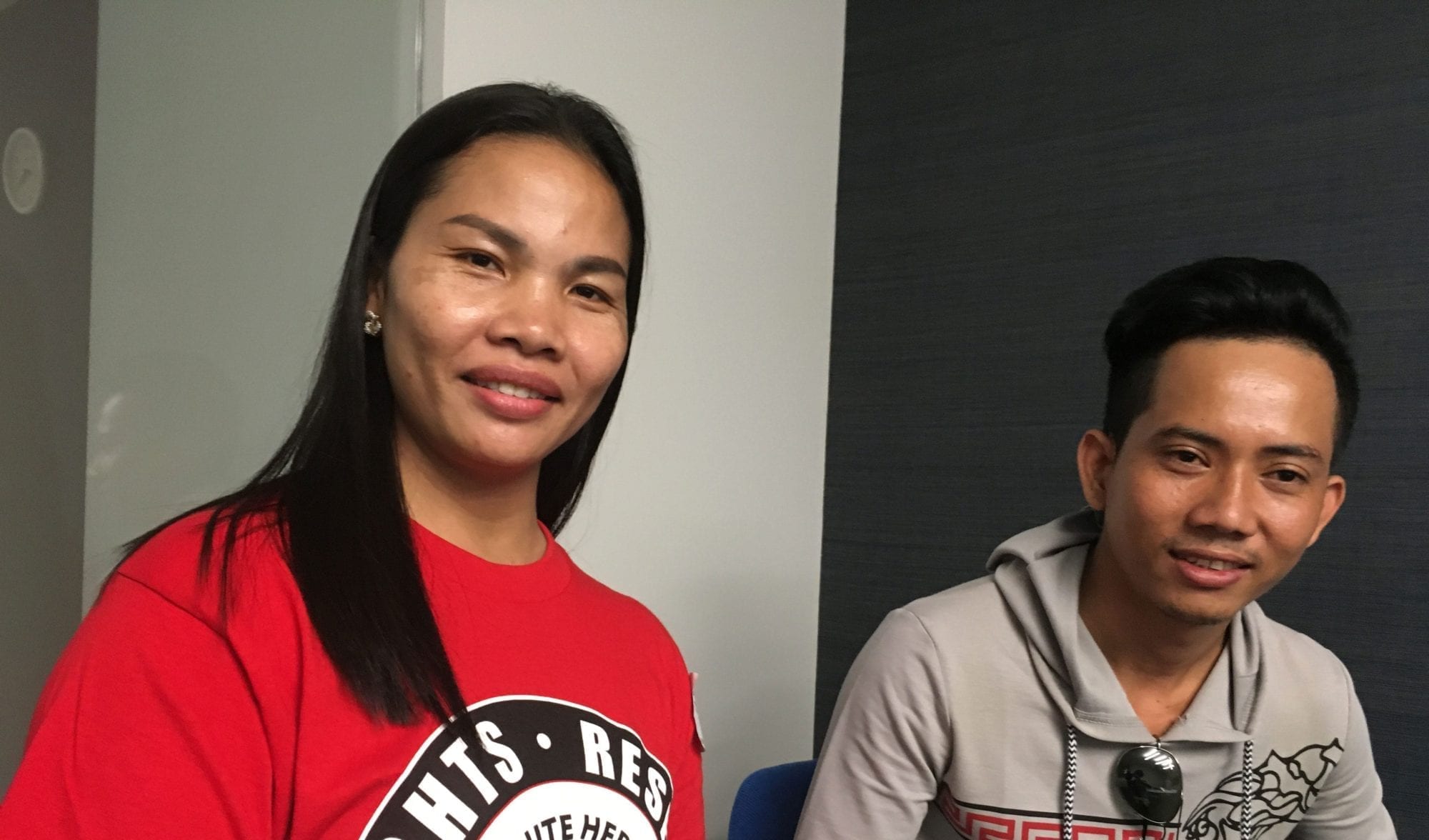

The company agreed to increase monthly wages by $15 in 2019 and $20 in 2020, which means “workers with the lowest wage could earn up to $120 [per month] next year,” local union president Tea Tuot told the Phnom Penh Post. The workers, most of whom are women, also will get a $25 per month pay boost if the agency governing the park renews the company’s contract in 2020, and additional increases in the following two years.

Tea, who says the company reassigned him to a worksite far from the union members, was returned to his previous position as part of the agreement.

After workers formed the Tourism Employees Union V-Green Co. (TEUVGC) in June 2018, they successfully pushed for a monthly wage increase from $71 to $80 and some social protections through the national social security system, including access to the national health care program and worker compensation benefits.

But further talks stalled late last year, and workers say the company began to retaliate against union activists, including Tea. The company has agreed to not impede union activity or retaliate against workers involved in the union.

Throughout the workers’ efforts to achieve justice on the job, the Solidarity Center provided the union, an affiliate of the Cambodian Tourism and Service Worker Federation (CTSWF), with legal and bargaining support.

Workers Don’t Share in Cambodia’s Booming Tourism Industry

Cambodia’s tourism sector earned $3.63 billion in revenue in 2017, an increase of 13.3 percent over the previous year. Yet workers collecting trash throughout the more than 400-acre site are not provided with protective gloves and face masks, exposing them to safety and health hazards like broken glass and hazardous chemicals. They also have little job security and were not paid overtime on Sundays and holidays as required by law.

In recent years, construction and restoration workers at the Siem Reap complexes also have sought to improve their poverty wages and highly dangerous working conditions, but like many workers in Cambodia, they face big hurdles when they seek to form unions and improve their working conditions, including retaliation, violence and even imprisonment, according to the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC).

Cambodian workers have waged few strikes in recent years since passage of a 2016 labor law that significantly limits workers’ freedom to form unions and exercise their rights to collective bargaining and free assembly, and workers celebrating their victory at V-Green hope their victory bolsters’ similar workers’ struggles around the country.

Aug 20, 2018

From the ancient temple complex of Angkor Wat to the palaces and pagodas of Phnom Penh, Cambodia draws vast numbers of tourists from around the world—more than 5.6 million in 2017—who help make the country the sixth fastest-growing economy in the world, with travel and tourism contributing 14 percent of total GDP in 2017.

But even as tourist visits accelerate and the economy booms, the hotel receptionists, room cleaners and maintenance staff essential to this economic growth are struggling to get their fair share of economic prosperity.

At the five-star Sofitel in Phnom Penh, where a room can cost up to $800 a night, base wages are $70 a month plus a percentage of the guest service charge, for a monthly salary of roughly $200 a month. Yet a basic living wage in Cambodia for one person is between $156 a month and $259 a month, and most workers have families to support.

“I want the employer to give a better base wage for employees,” says Phat Saroun, president of a newly formed union at the hotel. “I want to increase the base wage to $85 a month,” he says, speaking through a translator. Phat’s union is part of the Sofitel Phnom Penh Phokeetra Hotel Independent Solidarity Union (SPPHISU).

Phat and five other Cambodian hotel workers traveled to Washington, D.C., in recent days as part of a Solidarity Center delegation to meet and strategize with hotel union activists and other leaders in the U.S. union movement.

A Union Makes a Big Difference

Tourists to Angkor Wat can pay high prices for hotels, even as workers barely earn a living wage. Credit: Wikipedia

With no legal minimum wage in Cambodia’s service sector, the nearly 1.2 million jobs in travel and tourism offer low pay and precarious employment—unless workers succeed in forming a union.

“There are two Sofitels in Cambodia and at the one in Siem Reap, they have a collective bargaining agreement. At my hotel in Phnom Penh, working conditions are very different,” says Phat, who is working to achieve a single contract with both hotels.

In Siem Reap, where nearby Angkor Wat is Cambodia’s biggest tourist draw, Mao Vanda has been part of her 235-member hotel union since its formation 12 years ago. Now a union secretary and shop steward, Mao describes the many improvements workers have negotiated at the luxury Raffles Grand Hotel.

“Working conditions are better than before,” she says, speaking through a translator. “Monthly salaries now average between $160 and $170 in the off-peak season, and around $350 during the five busiest tourist months.

“For instance, before we had a collective bargaining agreement, women were paid only 50 percent of their base salary during the [legally mandated] 90-day maternity leave. After the collective bargaining agreement, women are paid their full salary and full guest service charge for 100 days after giving birth. If they require a surgeon, the employer gives them $500.”

Workers Fear Losing Their Jobs if They Form a Union

Yet despite the significant improvements in wages, benefits and working conditions for unionized hotel workers, challenges to forming unions means union only represent between 4,000 hotel workers and 5,000, says Nimol Vorng, Solidarity Center program officer in Cambodia.

Hotels frequently hire workers on five-to-six month contracts and as a result, “Workers are afraid to join a union because after the contract is finished, the employer won’t hire you any more,” he says.

Although workers in the travel and tourism sector account for 13.6 percent of total employment, “unions don’t have strong voice or the power to negotiate with employer,” he says.

Yet Phat, Mao and other workplace-level union leaders who met with U.S. union activists are striving to strengthen their unions at the workplace and throughout the country’s hotel industry, and they plan to take back to their unions the lessons and experiences they gleaned in the United States.

For Mao, that means planning big. “For every hotel, we want to have a standard [national] minimum wage,” she says.

Solidarity Center Exchange Programs are funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs.

Jun 5, 2018

Rural Cambodian villagers who say they were trafficked for forced labor in the shrimp processing industry in Thailand are challenging a ruling by a California federal district court that dismissed their case against the Thai and U.S. companies that benefited from their labor.

A coalition of human rights groups, led by the Solidarity Center, filed an amicus brief on June 1 in support of seven workers as their case goes to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The workers had brought their suit based in part under the U.S. Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA), which in 2008 was amended to extend civil liability to those who “knowingly benefit” from the trafficking of persons in their supply chains.

The December ruling of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California interpreted the TVPRA in a way that essentially ignored the “knowingly benefit” standard and instead required evidence that the U.S.-based companies actually participated in a venture to traffic the Cambodian workers into Thailand, according to Solidarity Center Legal Director Jeff Vogt.

The supporting brief argues, in part, that the companies knew or should have known of the widespread use of trafficked labor in the seafood sector in Thailand. Since 2008, numerous reports have exposed the trafficking of workers into Thailand to work in the shrimp industry. It would have been virtually impossible for enterprises involved in the shrimp industry not to have known of the extremely high risk of trafficking.

In 2016 alone, 16 million people were victims of forced labor by private enterprises, according to International Labor Organization estimates. This illegal activity generates $51 billion in profits.

Following the December court ruling (Keo Ratha, et al. v. Phatthana Seafoods Co. Ltd., et al.), Keo Ratha, one of the seven men filing the suit, told Voice of America Khmer that he deeply regretted the district court’s decision.

“I’m disappointed because we thought that the U.S. court would find justice for us,” he said. “But when the court dismissed our complaint I was speechless. This is their law.”

Joining the Solidarity Center in its brief are the Centro de los Derechos del Migrante, Earthrights International, the International Labor Recruitment Working Group, the International Labor Rights Forum and the Worker Rights Consortium.

Nov 15, 2017

“Informal workers are organizing and they will organize as long as there is injustice and oppression,” says Sue Schurman, distinguished professor of Labor Studies and Employment Relations at Rutgers University.

Sue Schurman, distinguished professor of Labor Studies and Employment Relations at Rutgers University, opened the Solidarity Center book launch. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

Opening a Solidarity Center book launch and panel discussions on Informal Workers and Collective Action: A Global Perspective this morning, Schurman also cautioned that unless unions focus on the issues unique to empowering workers who have no direct employer, workers in the informal economy will organize to improve their rights “with or without the existing trade union movement.”

Hosted by the AFL-CIO, the event launched the Solidarity Center daylong 20th Anniversary Celebration in Washington, D.C., which will culminate tonight with a festive event honoring U.S. Sen. Sherrod Brown and the Colombian and Honduran labor movements. Rep. Karen Bass and AFL-CIO Secretary-Treasurer Liz Shuler will host.

Edited by Schurman, Adrienne E. Eaton and Martha A. Chen, Informal Workers collects case studies from union campaigns in such countries as Brazil, Cambodia and Colombia, bringing together in one volume a compendium of academic field research and concrete grassroots examples. The book was produced by Rutgers and WIEGO with support from the Solidarity Center.

Highlighting the event, U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal, the first Indian-American woman in Congress, energized participants with an impassioned call to action.

AFL-CIO Executive Vice President Tefere Gebre opened the Solidarity Center book launch on informal workers. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

“This is about people standing up around the world and making it clear we have a very different vision,” she says. “It is about more jobs and better jobs for workers all over the world and that is the work of the Solidarity Center that we are grateful for.

“You are the ones who give me hope, working in countries around the globe in countries where organizing unions is sometimes life and death.”

“The work of the Solidarity Center around the world is very personal,” says AFL-CIO Executive Vice President Tefere Gebre, who addressed the opening session. “I was a refugee and dedicated my life to workers all across this country and world in support of their fights.”

A Broader, More Inclusive Labor Movement

Building a broader and inclusive labor movement by recognizing workers’ intersectionality is essential for unions to organize going forward, according to panelists.

“We can’t organize on the basis of class, or ethnicity, or gender—we must think about multiple identities,” says Janice Fine, associate professor of Labor Studies and Employment Relations, at Rutgers University.

Fine spoke on “Perspectives on Fighting for Social and Economic Justice for All,” the first of three panels.

Mary Evans from Rutgers discussed how female Cambodia beer sellers improved their status as women in their communities by joining together to better their workplaces. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

In Cambodia, where women beer sellers launched a grassroots social justice movement to improve their working conditions, and ultimately joined with unions, women have made tremendous progress in improving their status at work and in their communities, says Mary Evans, Labor Studies professor at Rutgers University.

“Beer worker women wanted dignity at work. There have been huge strides for women in Cambodia” where women have little status, she says.

Speaking about the need for unions to engage in “intersectional” organizing—inclusive, cross identity movement building, AFL-CIO International Director Cathy Feingold says, “ We need to build a campaign from the roots up, not at the place where we get stuck.

“Solidarity is multi-dimensional and horizontal,” she says. “We have to be saying, ‘I look you in the eye,’ not ‘I look down on you.’ ”

Speaking on the second panel, “The Impacts of Successful Organizing on Communities, Societies and Countries,” Evangelina Argüeta Chinchilla, National Coordinator at the General Workers Central (CGT) union confederation, described some of the challenges in organizing garment workers and negotiating bargaining agreements.

“Trade unions have been critical to the fight we are in”—Evangelina Argüeta Chinchilla, national coordinator at the General Workers Central (CGT) union confederation Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

“Trade unions have been critical to this fight we are in,” she says. “We have really been intentional about the unions being on the sideline in this struggle … and stand up to government and corporations and be the voice for the workers in this industry.” But the unions have not worked alone, she says. By partnering with women’s advocacy groups and anti-violence networks, unions have broadened their knowledge and expanded their allies in Honduras and around the world.

Argüeta and several Honduran garment workers will accept the honor award on behalf of the Honduran union movement at tonight’s 20th Anniversary Celebration.

Social Movement Unionism

Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau described how Tunisian unions joined a countrywide movement for social justice. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connel

Highlighting the Tunisian labor movement’s role in the 2011 Arab spring, Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau said unions initially played a supporting role to the grassroots opposition to dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.

Later, the labor movement made a choice to shift its political support to the people, and by calling a national strike in which 100,000 union members took to the streets, the union movement facilitated the election of a democratic government.

“What the labor movement did was recognize itself in this movement. Bread, freedom and liberty—that’s what the labor movement is about.”

In Buenaventura, Colombia, where port workers were paid low wages with no social protections after their jobs were subcontracted, workers went on strike despite a law prohibiting them from doing so because they were not formally employed, says Dan Hawkins, research director at the Escuela Nacional Sindical in Colombia.

The strike, says Hawkins, empowered the Afro-Colombian community because “it symbolized to people in a racially discriminated city where all people in power are white or mestizo, the importance of port workers standing up for their rights.”

In the Dominican Republic, where informal economy workers have no legal right to form unions, domestic workers joined together in an association to work for their rights, says Fine, who shared the results of her case study from Informal Workers. The efforts of the primarily Haitian women workers were key to moving 2011 passage of International Labor Organization Convention 189 on domestic worker rights, expanding the possibility of decent work to domestic workers around the world.

Summing up the conference discussion, Jayapal says, “Ultimately we need to recognize we need to help workers around the world. We need to take on racism and sexism and xenophobia because that’s what will make the union movement strong.”