Apr 20, 2017

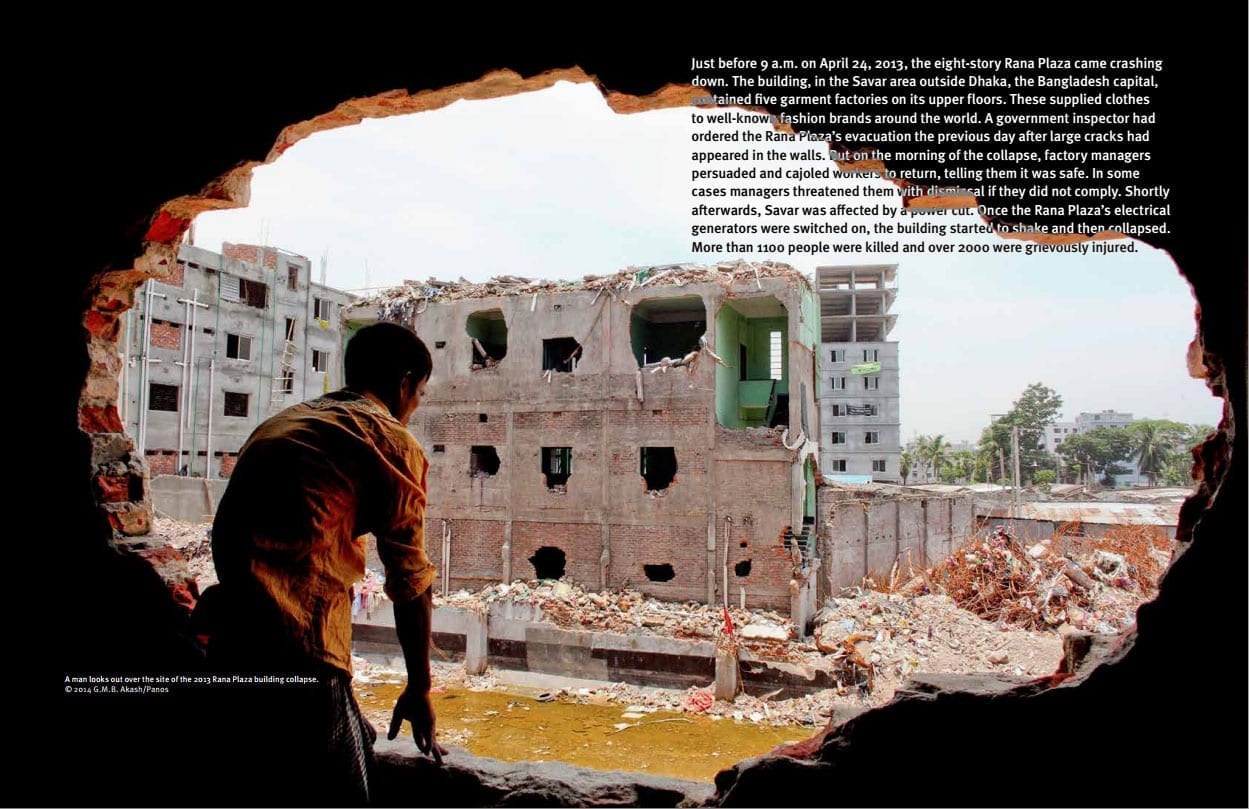

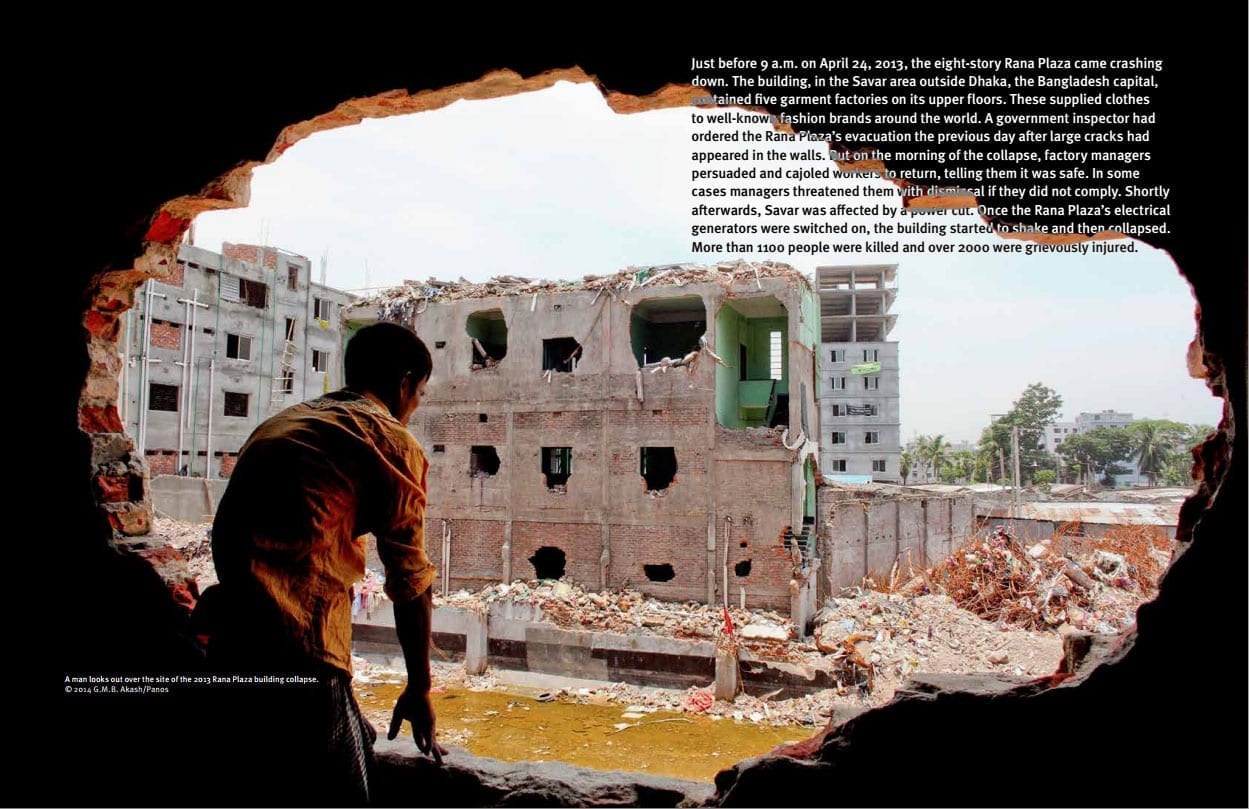

As we approach April 24, the fourth anniversary of the Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh that killed more than 1,130 garment workers and severely injured thousands more, the Solidarity Center is posting first-person stories of three garment worker union organizers who were deeply involved in the aftermath of Rana Plaza and who were arrested in December on baseless and dangerous charges, following wage strikes in the Ashulia garment district in December.

Mohammad Golam Arif, a long-time organizer with the Bangladesh Independent Garment Workers Union Federation (BIGUF) that has helped thousands of workers in 36 factories form unions, was one of the more than 35 people arrested in the December crackdown. Police took him from his home on December 22 and later charged him with involvement in a January 2015 political opposition violence case involving a bus burning in which he had no involvement. The case carries punishment of death or up to life imprisonment.

After being denied bail repeatedly, the high court eventually granted Arif bail. He was released on February 27 after spending 68 days in jail. The case is still pending.

Arif was among more than two dozen garment worker union organizers arrested for his union work.

“I got my first job as a garment worker in Mirpur (an area in Dhaka) in 1993 when I was 12 years old, making 300 taka ($3.60) a month as a thread cutter. My father told me he was going to bring me from the village to Dhaka so I could become a motor mechanic, but I missed the opportunity and started at a factory instead.

“The next year I changed factories, where there was one worker involved with a trade union and an active leader of BIGUF. He brought me to the inauguration program of BIGU (predecessor to BIGUF) in December of 1994. Management later terminated 22 workers in that factory for union organizing, and I moved on to another factory. But eventually I went back to this factory and helped organize a union there with the help of BIGU.

“In 1997, BIGUF got registered as a federation and my factory was one of the first six BIGUF-affiliated unions. I was general secretary of the union. Twice I was beaten by management (because of union activity).

“I started working in a garment factory again where I tried to organize another union. All workers united with BIGUF but management closed down the factory.

“After that, I started helping out with Solidarity Center’s fire safety program for garment workers at that time. I was a fire safety educator.

‘Instructions from a Higher Authority to Arrest Us’

“A lot has changed since Rana Plaza. And that’s one reason I began working full-time as an organizer for BIGUF. BIGUF is not politically affiliated. We actively work with the workers.

“When we were arrested (in December), we were physically and mentally worried but we knew we didn’t do anything. I am married with a five-and-a-half-year-old son. My wife learned that I was arrested after six days and my parents after one month. My mother was very worried but my father was strong since he knew I didn’t do anything.

“This kind of incident has happened in the past (arrests of activists) but this time it is also different. They are trying to destroy us by linking us to the (political) opposition parties.

“If they thought we had something to do with this, why didn’t they involve us in a garment case? They only told us after they arrested us that they had instructions from a higher authority that they had to arrest us.

“Initially, when we were arrested the workers couldn’t understand what had happened but they came to support us. Union leaders came to visit us in jail. When we are in danger, union leaders extend their support.”

Jan 6, 2017

In mid-December, a strike in Ashulia, an industrial suburb of Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka, and a ready-made garment sector hub, quickly snowballed into widespread unrest. Garment workers abandoned their factories to call for a living wage in response to ever-rising costs. Mass arrests and firings ensued.

The minimum wage for a Bangladeshi garment worker is $68 a month, an amount last fixed in 2013. When they took to the streets in December, workers were demanding the minimum be increased to $191 a month. Dhaka is the 71st costliest city in the world, in line with Montreal, Canada.

The strike started in Windy Apparels and rapidly spread to other units resulting in 60 factories suspending operations. On December 20, the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) ordered owners to reopen factories and resume operations after a five-day break. However, upon their return, more than 1,600 workers were notified that they had been laid off due to their alleged involvement in the unrest. Labor leaders and activists collectively demanded the reinstatement of all workers but received no response.

Windy Apparels is the same factory that denied a worker sick leave in October despite a very serious illness. She collapsed on the factory floor and died upon reaching the hospital. Her body was left at the factory gate for her husband to retrieve.

Since the factories reopened, union leaders and worker rights advocates have been detained or arrested on charges related to their alleged involvement in the strike. Union activists from different federations and from different areas of Dhaka—and unrelated to the Ashulia unrest—also have been swept up by police. Many have been charged under the Special Powers Act, 1974, which provides police with sweeping power to detain individuals. The act has been used to suppress political opposition and peaceful demonstrations, as well as to retaliate against individuals engaged in personal disputes with people in positions of authority.

Journalists and nongovernmental organizations that focus on worker rights are also being targeted and intimidated by security services. Ekushey Television Journalist Nazmul Huda, was arrested on December 23 and held in police custody for two days−during which time he was allegedly tortured−on charges of inaccurate reporting on the strike.

Last week, police arrived at a community center operated by the Bangladesh Center for Workers Solidarity, an ally of the Solidarity Center, and ordered its closure.

As a result of this and the arrests of union leaders who had no role in the unrest, a chilling effect has taken hold with some other union federations closing offices even though they have not been ordered to.

International worker rights organizations, including the Solidarity Center, are monitoring the situation, and the Solidarity Center continues to track the registration of garment-sector unions in the country.

Donate now!

Your tax-deductible contribution to the Bangladesh Worker Rights Defense Fund will support Bangladesh garment organizers and worker-activists as they help workers who toil in unsafe factories for unfair—or unpaid—wages and who, without a union, cannot exercise their rights.

Activities your donation may support include:

• Medical care following an attack

• Safe spaces for organizers and their families who must go into hiding

• Legal assistance

• Transportation

• Awareness-raising activities regarding attacks on worker rights

• Replacement of belongings stolen during assaults

Your receipt for supporting Bangladesh organizers and activists will indicate The Solidarity Center Education Fund. The Fund is a tax-exempt charitable organization under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Your contribution is tax deductible to the extent allowed by governing laws. In addition, pursuant to the Internal Revenue Code requirement stated in Internal Revenue Service publication 1771, no goods or services were provided in return for this contribution.

Nov 23, 2016

On the eve of the tragic Tazreen Factory Ltd. fire that in 2012 killed 112 garment workers in Bangladesh, Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau discussed on the Working Life podcast published today how global inequities led to Tazreen and to the 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh—and how unions can enable workers to help prevent such disasters.

Describing her visit to the burned-out Tazreen factory, Bader-Blau says workers who survived the collapse met with her.

“They told me that they had tried to form unions in that building … and their union organizing efforts were busted by the supervisors and the employers,” she says. “They told me that had they had trade unions, they really believe they would have had more power vis à vis the supervisors and the company to negotiate things like safety improvements for themselves and adequate wages for themselves and their families.

“When workers do have the ability to form and join trade unions, they can bargain to improve their wages, they can bargain with their employers to make their conditions better. Work should be about dignity.”

Listen to the full podcast here.

Nov 22, 2016

On November 24, 2012, a massive fire tore through the Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killing more than 110 garment workers and gravely injuring thousands more.

To mark the fourth anniversary of Tazreen, a new Solidarity Center photo essay depicts the system of exploitation in the global garment industry that made the fire at Tazreen so devastating, and showcases how workers have been standing together since the disaster to fight for safer working conditions and greater respect for their rights at work.

Dying for a Job: Commemorating the Anniversary of the 2012 Tazreen Factory Fire, illustrates how with the Solidarity Center, which partners with unions and other organizations to educate workers about their rights on the job, garment workers are empowered with the tools they need to improve their workplaces together.

Sep 19, 2016

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry met with leaders of Bangladesh garment unions recently in Dhaka, where he emphasized workers’ ability to freely form unions as key to workplace safety.

“Enhancing worker safety has to be paired with strengthening workers’ rights,” he told a group of 60 garment workers and allies.

“The fact is garment factories across Bangladesh actually could benefit enormously from empowering laborers, allowing them to form labor unions, affording them full collective bargaining rights, because no one should ever be compelled to work in hazardous or exploitative conditions. It’s really that simple.”

Worker Prosperity Possible with Worker Rights

At the event, which took place at the Edward M. Kennedy center in Dhaka, the capital, Kerry drew parallels between the efforts of Bangladesh garment union leaders to empower workers and Sen. Edward Kennedy’s strong support for working men and women.

“Bangladesh cannot truly meet the aspirations of its people and share prosperity if its workers are not safe and their rights are not ensured.

Kerry noted how “the $28 billion garment industry has played a uniquely important role” in the rise of Bangladesh’s economy. But he cautioned, “Growth on its own—growth just for its own sake—is not our only goal. You can grow and grow and grow and grow, but you can be growing with the wrong values, you can be growing with the wrong outcomes, you can be growing with people not gaining in their rights or in their income or in their ability to get an education.”

Kerry met with six garment worker union federation leaders: Babul Akter from the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF); Amirul Amin from the National Garment Workers Federation (NGWF); Nazma Akter, Sommilito Garments Sramik Federation (SGSF); Sritee Akter, Garment Workers Solidarity Federation (GWSF); Roy Ramesh, United Federation of Garment Workers (UFGW); and Raju from the Bangladesh Independent Garment Union Federation (BIGUF). Two factory union leaders affiliated with BGIWF, Munna and Rina, also attended.