Aug 30, 2019

A devastating fire in Dhaka’s Jhilpar slum earlier this month highlights the deplorable living conditions suffered by low-wage workers producing clothing for the global marketplace in Bangladesh’s highly profitable garment sector. The August 16 fire destroyed thousands of tin shacks and left an estimated 15,000 families homeless. This week, Solidarity Center partners Akota Garments Workers Federation (AGWF), Sommilito Garments Sramik Federation (SGSF) and AWAJ Foundation distributed relief funds to 175 union families impacted by the fire but say that only higher wages can provide a long-term solution to dangerous housing.

“Garment workers, many of whom are young women supporting families, deserve wages that afford them reliably safe living conditions,” says Solidarity Center Asia Regional Director Tim Ryan.

Fire disasters are a regular occurrence in Bangladesh’s major cities, killing hundreds of people in recent years. Dhaka and Chittagong, where many garment workers live and work, are especially prone to fires. At least 100 people have died in Dhaka fires so far this year; more than 70 were killed in February when a fire razed several Dhaka apartment buildings also being used to warehouse chemicals.

While garment workers are safer on the job due to progress made through the Bangladesh Accord—an enforceable international agreement between unions and more than 190 global apparel brands and retailers that covered more than 1,600 factories last year—low wages are forcing garment workers to live in dangerous slums. Dhaka has more than 5,000 slums inhabited by an estimated four million people, including children.

Although Bangladesh’s garment worker minimum wage increased in 2018 to $95 per month—the first increase in more than five years—wages are not keeping pace with the rising cost of living in areas populated by the apparel sector and employers are not paying workers a living wage.

“Poverty wages are forcing garment workers into over-crowded slums, where fire and other health risks are high,” said Ryan.

Through the efforts of AGWF, SGSF and AWAJ Foundation, with Solidarity Center support, 175 union families whose homes were destroyed in the August 16 Jhilpar fire yesterday received relief funds to help them rebuild. Unions will continue to inventory their member’s losses and needs and distribute additional funds as they become available.

Relief recipient Shima, who lost her home in the fire, said that union assistance gives garment workers like her the strength and means to rebuild, but that workers must earn enough to afford safe housing.

“Relief funds after disasters are only temporary,” she said.

Workers attempting to secure their fair share of revenue generated by the apparel sector—$32 billion in 2018—have been met with blatant intimidation by factory owners. 11,000 Bangladesh garment workers were fired in the wake of strikes they waged in December 2018 and January 2019 to protest low wages. Many seeking to form unions or take collective action were physically threatened and attacked, and some were arrested on trumped-up charges.

At least 1,304 garment workers were killed and at least 3,877 injured in factory fires and other workplace incidents in Bangladesh from November 2012 through April 2019, according to data compiled by the Solidarity Center.

Apr 23, 2019

Six years ago, the preventable Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh killed 1,134 garment workers in the world’s worst garment industry disaster. Corporate greed, inadequate labor and building code enforcement, and worker exploitation all contributed to the April 24, 2013, tragedy, which spurred efforts to improve factory safety and support workers seeking a voice on the job.

Nurunnahar mourns the loss of her daughter who died in the Rana Plaza collapse. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Many survivors still face unemployment and poverty because they are too injured to work, according to an Action Aid survey. Months before Rana Plaza collapsed, a fire at Tazreen Fashions factory killed more than 112 workers, part of a pattern of dangerous conditions and deadly risks garments workers face each day in Bangladesh.

Following Rana Plaza, Bangladesh has seen important international and domestic efforts to address fire and building structure risks and improve the labor conditions that hinder workers from reporting dangerous working conditions and violations, and exercising their labor rights. Initiatives like the Bangladesh Accord for Fire and Building Safety, a binding agreement involving fashion brands, unions and the government that helped make many garment factories safer, fueled a rise in union organizing.

And through worker education, like the Solidarity Center’s Fire and Building Safety program, garment workers are boosting their capacity to identify safety and health problems at the workplace and learn about their right to join together to ensure safe workplaces by taking collective action to resolve problems.

6,000 Garment Workers in Solidarity Center Fire Safety Trainings

More than 6,000 Bangladesh garment workers have participated in Solidarity Center safety programs in recent years, including Shilpi Akter, who has worked in the garment industry for more than 10 years.

Some 6,000 Bangladesh garment workers have taken part in Solidarity Center fire safety trainings. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

“Before the Rana Plaza incident, there were no sprinklers, fire doors or emergency lights in our factory,” she says. “I had no idea what fire or health and safety at work meant, neither did we have any trade unions or safety committees.

“Through Solidarity Center’s fire safety training, I learned how to use a fire extinguisher, how to be safe from the fumes during a fire accident, and that I must not keep the clothes I stitch near the heated motor of the machine. This knowledge was unknown to me even a few years back.”

Bilkis Begum, a garment worker and a union president, says before Rana Plaza, “we handled the toxic chemicals without any precaution and had no idea on what to do in case of a fire accident except to run.”

Mohammed Ronju paints the incident more starkly. “There would be no Rana Plaza if it had a union,”’ says Ronju, who has worked in the garment industry for 15 years. If workers had a union, they “would not go inside the building when they sensed trouble. They would have strongly resisted the pressure from management to go inside a building about to collapse.” The day before the Rana Plaza disaster, building engineers declared the structure unsafe. Yet managers threatened to withhold wages if workers did not show up for work the day Rana Plaza collapsed.

‘No More Rana Plazas’

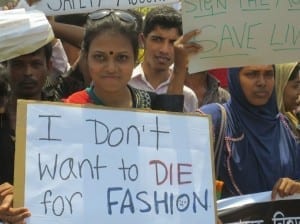

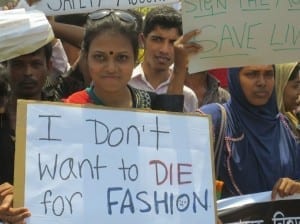

Each year, tens of thousands of Bangladesh workers rally on the anniversary of the Rana Plaza disaster to demand safe working conditions. Photo: Solidarity Center/Sifat Sharmin Amita

The Rana Plaza tragedy prompted international efforts, through the Accord and other mechanisms, to ensure dangerous garment factories were closed or repaired and safety measures instituted. As a result, factory compliance with fire and building safety codes has improved. Yet much more work remains to be done to ensure full compliance with basic fire and building safety and occupational health standards, and to guarantee enforcement of fundamental labor laws, including workers’ right to form unions.

Since November 2012, at least 1,304 Bangladesh garment workers have been killed and at least 3,877 injured in factory fires and other workplace incidents, according to data compiled by the Solidarity Center.

All the more reason, experts say, the Bangladesh government must not roll back international safety inspections.

Says Bilkis Begum: “Surely, we all would agree that it should never be the case that we could sacrifice another Rana Plaza to complete the remaining task of making the workplace safe for the garment workers of Bangladesh.”

Apr 17, 2019

On a recent Friday, the only day off for Bangladesh garment workers—if they get a day off—I went to visit workers at their homes to better understand how the people who stitch our clothes live their lives. Walking through the puzzling narrow alleys, I entered a tin shed-like building. A corridor tore through the center and on each side were rooms for families. It was in one of these dimly lit rooms where I met Konika, who worked as a sewing operator in a nearby garment factory in Gazipur. In the tiny space where she lived with two children and her husband, she revealed the conditions at her workplace.

A garment factory in Gazipur. Credit: Solidarity Center/Istiak Ahmed Inam

“We are under intense pressure to meet the target production,” she says. “I used to produce 70 pieces an hour but now, after our minimum wage has been increased by the government, I must produce 90 pieces. I have to think twice if I want to use the washroom. What if I miss my deadline? What if my production manager sees me? I rest only if there’s a problem with my machine and am lucky if the mechanic is not close by.”

Worker Safety under Threat Again

Six years after the deadly April 24, 2013, Rana Plaza building collapse killed 1,134 garment workers and injured hundreds more, the government is on the verge of rolling back international safety inspections even as employers and the government are blocking workers’ ability to exercise their right to form unions to improve working conditions.

Disasters like Rana Plaza or the 2012 Tazreen Fashions fire, which together killed more than 112 garment workers, prompted global outrage and mobilized workers in protest of unsafe and deadly working conditions, forcing major fashion brands and Bangladesh suppliers to address safety issues. As a result, unions, suppliers and many international brands formed the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, a binding agreement that helped make many garment factories safer. Despite its success, however, the accord may be dismantled, leaving workers at the mercy of a system unprepared to improve factory safety, according to a recent report.

Meanwhile, fashion companies often send their own inspection teams to factories, but the effectiveness of these visits is debatable.

“Our managers make us tell the foreigners [safety inspectors] we don’t work until 10 p.m., that we receive our wages regularly and we even receive our doctor’s fees. None of this is true,” says Konika. On many occasions, the inspection team strolls around the factory, only gathering data from factory management and not from the workers, thus releasing inaccurate reports.

Konika and her co-workers face odds that would dishearten many: factory owners escalating pressure to produce and depriving workers of their basic rights, and corporations wearing a mask of “doing all they can” for workers, while in fact, doing nothing.

Yet Konika, on her day off, enjoys time with her family, despite recognizing the injustices she is likely to face tomorrow.

Feb 14, 2019

Tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers waged weeks-long strikes in December and January to protest low wages and unequal pay increases—and now workers say factory employers are using the walkouts to further repress their efforts to form unions and collectively bargain better wages and working conditions.

More than 11,000 garment workers have lost their jobs or faced repression as a result of the wage protests, and employers and the police have filed cases against more than 3,000 workers, according to the global union IndustriALL. Many workers fired say they were not involved in the protests.

During the walkouts, police used tear gas, water cannons, batons and rubber bullets, reportedly injuring dozens of workers and killing 22-year-old Sumon Mia, a worker at Anlima Textile in Savar, who was shot dead on his way back to work from lunch.

Billboards with names and photographs of terminated workers have been posted at some factories as an intimidation tactic, and union leaders say factory management is exploiting the walkouts to target and blacklist them from employment in the sector.

Factory walkouts began the second week of December, when mostly nonunion garment workers from roughly 350 factories in Gazipur, Ashulia and Narayanganj protested the elimination of the 5 percent annual wage increase for 2018 and a basic wage increase applied unequally to workers with various skill levels.

Recent Repression of Worker Rights Part of Longer Trend

Following the deaths of more than 1,200 garment workers in the 2012 fire at the Tazreen Fashions factory and the 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse, workers vigorously organized to form unions and negotiate contracts, as the Bangladesh government and ready-made garment (RMG) employers responded to international pressure to improve safety and wages.

But in recent years, employer harassment—including physical attacks and threatening home visits—and government resistance to workers seeking to register unions have meant even fewer workers can join together to collectively improve their workplaces. As recently as November 2018, two union organizers were brutally attacked by men associated with factory management, according to union leaders.

At the same time, Bangladesh’s highest court threatens the expulsion of the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh established after the Rana Plaza disaster. The legally binding agreement between hundreds of primarily European corporate retail brands and unions conducted safety inspections at more than 1,000 factories and educated workers on safety and other workplace rights.

Bangladesh is the biggest producer of garments in the world after China, with apparel exports totaling more than $30 billion last fiscal year. Although the Bangladesh RMG industry is by far the country’s biggest export earner, wages remain the lowest among major garment-manufacturing nations. Yet the cost of living in Dhaka is equivalent to that of Montreal.

Dec 13, 2018

More than five years after the Rana Plaza and Tazreen Fashion disasters killed more than a thousand garment workers and injured many more, workers in ready-made garment factories in Bangladesh still struggle to make ends meet. And even now, garment workers often are forced to work in unsafe and unhealthy conditions.

Workers recently interviewed by the Solidarity Center say their employers set harsh production demands with short timelines. In fact, following the government’s recent minimum wage increase from $63 a month to $95, management in some factories pre-emptively set higher production targets. As a result, workers face unbearable pressure to work more quickly and produce more.

Verbal abuse and insults, such as name calling, is routine, workers say.

Many, like Shefali, also suffer from severe health problems after working between 10 and 14 hours per day.

Shefali, who asked that her real name not be used for fear of retaliation, says she is unable to sleep for several hours at a stretch because of pain. Other workers who stand long hours on factory lines say they are unable to sit for extended periods because of joint pain.

Putting Solidarity Center Fire Safety Training into Practice

And for many workers, fire safety is still a danger in many factories. To address the issue, the Solidarity Center’s ongoing fire safety trainings have reached thousands of garment workers, who learn how to extinguish fires, provide first-aid during incidents and safely handle chemicals. They also learn how to identify risks in building safety, abrasions in wiring and machine equipment and how to report those risks to management to help prevent their factories from becoming another Rana Plaza.

The trainings also provide workers with a platform to come together and share their workplace hardships and strategies for improving their work environment.

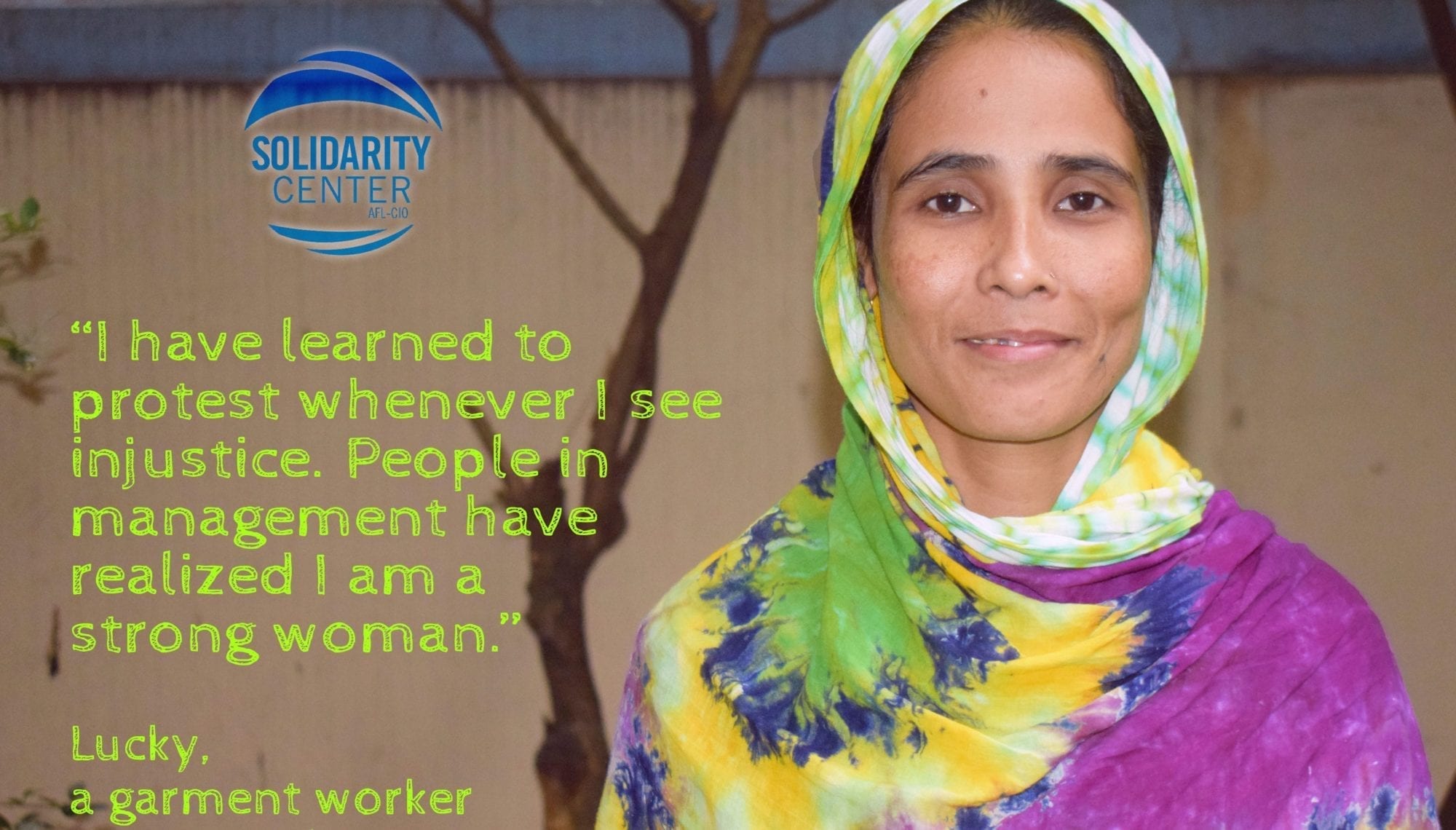

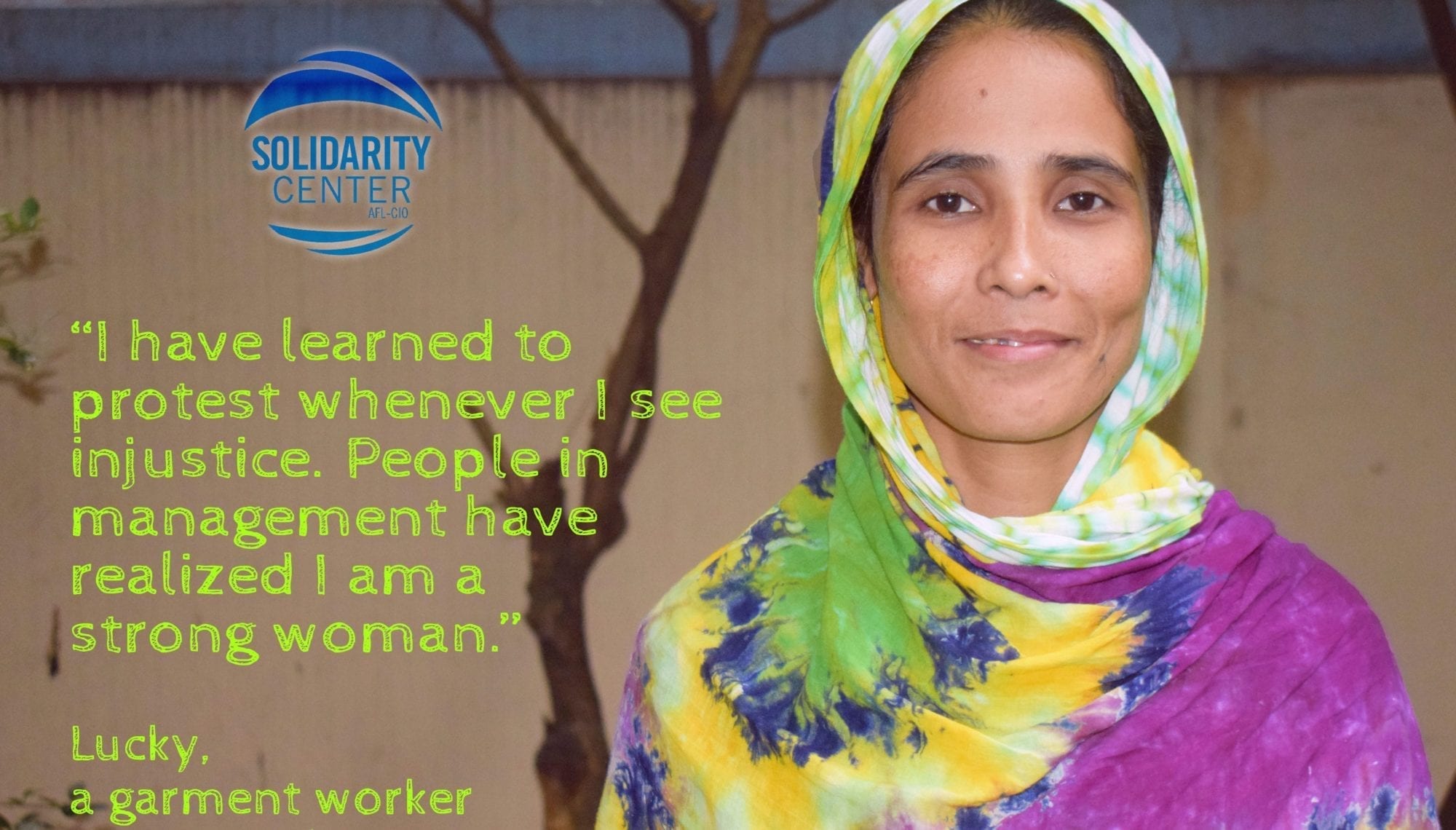

Lucky, who participated in one of the safety trainings, has put the lessons into practice.

“Once, there was fire in our factory and everyone rushed at the gates to escape. I saw a pregnant woman who was injured, and I could not leave her there alone. It is not by fire that people die but from the struggle during escape that causes death. So, I grabbed another colleague of mine and went to her to help. I wrapped my scarf around her as quickly as possible and pulled her out to safety,” she said.

Lucky added: “In another instance, I helped put out a fire at my neighbor’s home when no one could do it. I dipped a sack in the nearby river and threw it over the gas burner. People were amazed and said, ‘How can a woman do this?’ I learned this from all the training sessions I participated in over the years. It was really fruitful as I implemented what I learned a number of times inside and outside of my workplace.”