Dec 3, 2014

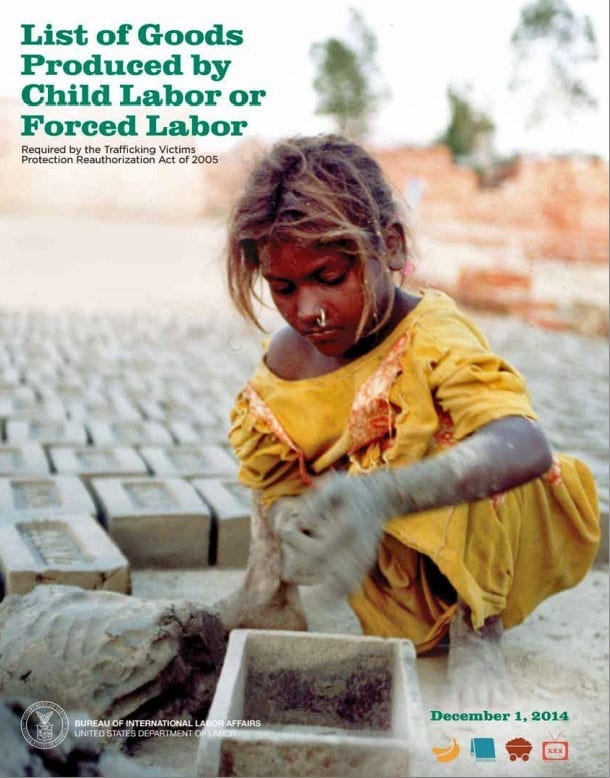

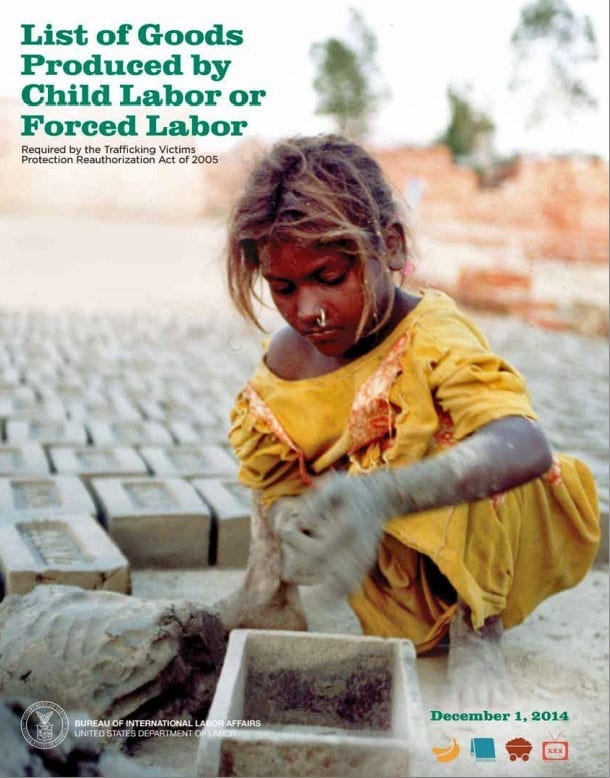

Cotton production involves the most child labor and forced labor in the world, according to the 2014 “List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor” by the U.S. Labor Department’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs.

Overall, 126 goods are produced annually by child labor and 55 goods produced through forced labor. Most of the goods, like cotton, are found in common items like T-shirts or are among popular foods, such as melons and rice.

The sixth annual report, released this week, added 11 goods produced with children’s labor: garments from Bangladesh; cotton and sugarcane from India; vanilla from Madagascar; fish from Kenya and Yemen; alcoholic beverages, meat, textiles and timber from Cambodia; and palm oil from Malaysia. Electronics from Malaysia made the list for being produced with forced labor.

Uzbekistan, listed among countries using forced labor, including children, for cotton production, routinely requires teachers to leave classrooms and work in the country’s annual cotton harvest, according to a report the Uzbek-German Forum issued last month.

The lengthy list of goods produced with child labor and forced labor includes garments, fish coffee, shrimp and other shellfish, tea, corn, tobacco and peanuts.

See the full list.

Nov 21, 2014

November 24 marks the two-year anniversary of the deadly fire at Tazreen Fashions Ltd. in Bangladesh that killed 112 garment workers. Since then, at least 30 garment workers have died in factory fires and 844 have been injured in 68 incidents, according to data collected by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the capital. Many of the survivors and their families say they have received little or no compensation, and many survivors are unable to work again.

“Things are getting much, much worse for me,” said Shahanaz, who sustained critical injuries, including loss of vision in her right eye, while fleeing the burning building. “With all of the pain I am in, I can no longer pray while standing.”

Shahanaz is one of nearly a dozen garment workers and family members the Solidarity Center profiled last year. Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka recently visited the workers again, and found that, like Shahanaz, their health and financial situations have deteriorated.

Five months after the Tazreen fire, another 1,100 garment workers in five factories were killed and another 2,500 people were injured when the Rana Plaza building collapsed.

Millions of garment workers, up to 90 percent of whom are women, have made Bangladesh the second largest producer of apparel globally, and 80 percent of the country’s foreign exchange depends upon the industry. Garment workers have toiled for decades in hazardous working conditions with few worker rights. After the Tazreen and Rana Plaza disasters shocked the world, these worker rights violations could no longer be ignored.

Following the Rana Plaza collapse, the United States suspended its Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) agreement with Bangladesh based upon chronic and severe labor rights violations. In the weeks after the suspension, the Bangladeshi government dropped charges against two prominent garment union leaders. It has since registered more than 200 unions representing more than 50,000 workers. By contrast, only two garment unions were registered between 2010 and 2012.

Yet some 25 percent of new unions are in factories that have closed or are inactive due to anti-union activities, according to Solidarity Center data. Further, in at least 46 factories with unions, workers have faced severe anti-union violence, mass terminations and/or threats.

International retailers have joined together in two separate groups to improve safety at factories where they contract work. More than 175 international retailers signed on to the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, a legally binding agreement negotiated with the global unions, IndustriALL and UNI. Another 26 primarily U.S. and Canadian companies signed the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, which is not legally binding. After inspecting some 1,700 of Bangladesh’s 5,000 garment factories, the Accord and the Alliance identified 33 factories in which safety issues are so serious that they recommended production be suspended because of the risk to workers.

However, questions remain about who will pay for the cost of repairs and who inspects the remaining factories that neither the Accord nor Alliance says are their responsibility. The Accord and Alliance claim 1,800 factories are under their purview, but a recent study estimated the total number is between 5,000 and 6,000 factories and facilities.

The Solidarity Center has had an on-the-ground presence in Bangladesh for more than a decade. This year, following Solidarity Center fire safety trainings, garment workers have used their new skills to identify and correct problems at their worksites. Joni and Rabeya, president and general secretary of B. Brothers Garments Co. Ltd. Workers Union, found 15 expired fire extinguishers and located electrical hazards in their factory, such as faulty electrical wiring. They raised these fire safety issues with management, which has since corrected some of the issues.

Recognizing that workers who freely form unions can better advocate for job safety and decent wages, the Solidarity Center believes there is need for:

• A clear and transparent trade union registration process.

• Quick resolution of unfair labor practices by the Bangladesh Labor Department, with penalties for employers who engage in them.

• Development of an independent alternative dispute resolution mechanism in the face of inefficient labor courts

Sep 29, 2014

Mukta, who works in a shrimp factory in Khulna, Bangladesh, makes $50 per month but that wage is not enough to support his family.

“Although employers should raise wages every year according to the law, they don’t follow the rules,” he said. “I have worked in my factory for nine years and my salary has increased only once.”

Mukta joined a meeting on the wages in the shrimp and fish processing industry with representatives from labor, business and civil society last week. Organized by the Solidarity Center and Social Activities for the Environment (SAFE), the event in Dhaka, the capital, featured Md. Mujibul Haque Chunnu, state minister at the Ministry of Labor and Employment.

The government recently directed the Minimum Wage Board to reassess the minimum wage for workers in the shrimp and fish processing sector. The board, established in 2009, has not revisited the wage level since then.

“It has been five years since the minimum wage was reviewed in the sector,” said Solidarity Center Bangladesh Country Program Director Alonzo Suson. “Now is the time to move toward a new consensus for a living wage for workers in the shrimp industry. A new minimum wage level will not only benefit the workers but the entire community and can make good business sense for a more productive sector.”

Representatives from SAFE, the Bangladesh Frozen Foods Exporters Association (BFFEA) and an academic from Rajshahi University presented their analyses and recommendations based on current conditions and wage levels in the sector. Participant, including union leaders, members of parliament, employers and nongovernmental organizations, then engaged in a vigorous discussion.

Shaheen Anam, executive director of the Manusher Jonno Foundation, a human rights foundation that helped support the event along with U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), noted the improved working conditions in the shrimp and fish processing sector which resulted from the work of “labor activists over the last several years.” But Anam pointed out that “these activists have faced a lot of threats … especially in the Khulna region.”

In 2013, the BFFEA, the Bangladesh Shrimp and Fish Foundation (BSFF) and the Solidarity Center signed a memorandum of agreement to implement worker rights according to Bangladesh labor law and International Labor Organization (ILO) core labor standards and to give workers the right to form trade unions.

Sep 19, 2014

Three times each month, dozens of women gather in dusty courtyards in rural towns in Manikganj, Dinazpur or other districts across Bangladesh to learn all they can about the only means by which they can support their families: migrating to another country for work.

In leading these information sessions, the Bangladesh Migrant Women’s Organization (BOMSA) seeks to assist women in understanding their rights—from what they should demand of those who facilitate their migration, to the wage and working conditions at the homes in Gulf and Asian countries where they will be employed as domestic workers.

“What I want for these women is that they are safe, they get their wages,” said Sheikh Rumana, BOMSA general secretary. Rumana founded the organization in 1998 with other women who worked with her for years in Malaysian garment factories. Before she migrated for work in Malaysia, Rumana was promised a good salary at an electronics plant. But when she arrived, she was put to work at a plant making jackets and paid pennies for each piece she sewed.

The gap between the promise and reality of migrating for work overseas is the focus of migrant worker activists across Asia. This month, Rumana and seven other migrant worker activists from Bangladesh, India and the Maldives are traveling across the United States as part of a Solidarity Center exchange program supported by the U.S. State Department. The group is meeting with U.S. activists working on labor rights, migrant rights and anti-human trafficking issues in Washington, D.C., New York and Los Angeles to discuss best practices to promote safe migration and share ideas for raising awareness about the risks of migrating for work.

Like BOMSA, the Welfare Association for the Rights of Bangladeshi Emigrants Development Foundation (WARBE-DF) assists those seeking to migrate, provides support for workers overseas and assists them upon their return. The organization also has successfully pushed the Bangladeshi government to ratify the United Nations (UN) convention on the protection of migrant workers, and is campaigning for passage of the International Labor Organization (ILO) convention covering decent work for domestic workers, said Jasiya Khatoon, WARBE-DF program coordinator and Solidarity Center exchange participant.

“Lack of job opportunities” is what drives millions of Bangladeshis out of their country in search of work, Khatoon said. Some 8.5 million Bangladeshis are working in more than 150 countries, according to 2013 government statistics.

Many workers migrating from Bangladesh and elsewhere are first trafficked through another country—where a lack of proper documentation may result in their arrest. In Mumbai, India, a transit point for many migrants, human rights lawyer Gayatri Jitendra Singh works both to assist imprisoned migrant workers and to change the country’s laws so that, rather than penalizing migrant workers, the laws recognize the culpability of traffickers and corrupt labor brokers.

Singh, a former union organizer, and other migrant advocates, point to the actions of labor brokers as the biggest underlying problem in the migration process. Many labor brokers charge such exorbitant fees for securing work that migrant workers cannot repay them even after years on the job, essentially rendering them indentured workers. They remain trapped, often forced to remain in dangerous working conditions because their debt is too great. Unscrupulous brokers also lie about the wages and working conditions workers should expect in a destination country, the migrant advocates say.

Singh and the other migrant advocates came to the United States filled with fresh stories about the suffering of migrant workers and their families: a Bangladeshi domestic worker in Jordan and another in Lebanon who had just returned to Bangladesh, still suffering the effects of nightly sexual abuse by their employers; the family of an Indian construction worker who died in Qatar and is unable to pay for the return of his body; the 12-year-old Bangladeshi girl whose passport cites her age as 25 so she can migrate overseas to support her family because her father is ill.

Bangladeshis “wouldn’t go if there were jobs in their country,” said Rumana. But faced with grinding poverty and no chance for decent work in Bangladesh, they uproot their lives to make a living. But as long as they do, Rumana said, they “shouldn’t have to be tortured to have work.

Sep 16, 2014

Some 600 factory-level garment union leaders and workers from 35 factories met during the recent Bangladesh Garments and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF) Convention in Dhaka, the Bangladesh capital.

Joining together under the convention theme, “Together we can bring change,” participants described the workplace improvements that followed after workers formed unions.

“Before forming the union, the workers were abused in different ways. For instance, if the production target was not fulfilled, management terminated them,” said Md. Khokhon Skikdar, general secretary of Lufa Garments Ltd. “But now, they (the managers) value us and hold mutual discussions.”

Tania Akhter, general secretary, Luman Fashion Workers Union, said before workers formed a union at Luman, “if any worker could not fulfill the production target, management forced them to work without any payment.” Now with union representation, “they receive earned leave pay, maternity leave and overtime wages due them as guaranteed by the labor law of Bangladesh. They are ensured of their rights after getting involved with union activities in the factory.”

Through their union, workers have achieved concrete workplace improvements “which were quite impossible earlier,” said Salma Akhter, joint general secretary of Winy Apparels Workers Union. “After forming a union, we increased our evening shift bill and got maternity leave.”

Participants also said the sixth annual BIGUF convention enabled them to expand their knowledge and skills and network with their peers.

“This type of convention gives us an opportunity to meet other union leaders and to get closer to each other,” said Skikdar. “Not only the leaders joined the program but also the members of the union were here.”

Mim Akhter, general secretary of the Dress and Domestic Workers Union, said she learned a lot speaking with other union leaders and now plans to “spread that knowledge among the general workers of the factory.”

Mim took part in training programs where she said she gained helpful knowledge, especially “how to deal with management” and “what is good and bad for the workers.”

Tania Akhter said the convention allowed factory leaders the meet and discuss mutual issues. “I feel very happy after seeing lots of workers together under one roof. As a leader, I am always trying to play a significant role in establishing worker rights,” she said.

Alonzo Suson, Solidarity Center Bangladesh country program director, IndustriALL’s Roy Ramesh and Rob Wayss, from the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, attended the convention as guests.

Unions participating included: Rokhsana Knit and Composite Workers Union; Miti Apparels Ltd. Workers Union; Fashion Island; Lucid Apparels Ltd. Workers Union; Lyric Industrial Workers Union; M F Apparels Workers Union; B Brothers Workers Union; Natural Apparels Ltd. Workers Union; Style Fashion Workers Union; BP Garments Workers Union; Essex Ltd. Workers Union; Four S Apparels Workers Union; Jisas Fashion Workers Union, Solar Garments; Super Shine Apparels Ltd. Workers Union; Workers Union; GNG Fashion and Fabrics Ltd. Workers Union; Overseas; Mega Star Apparels Ltd. Workers Union; Green Granite; Apollo Swing and Garments Ltd. Workers Union; New Morning Apparels Ltd. Workers Union; Global Knitwear Workers Union; Isabpur Workers Union; Aramic (Cement) Workers Union; Lokhipur Chingripona (Shrimp) Workers Union; Grameenphone union; and the Dockyard Union.