Apr 20, 2015

Bangladesh garment workers often risk their health and their lives at unsafe factories, and when they seek to form unions to address workplace problems, “factory managers continue to use threats, violent attacks and involuntary dismissals in efforts to stop unions from being registered,” according to a Human Rights Watch report released today.

“I was beaten with metal curtain rods in February when I was pregnant,” one garment worker told HRW. “They wanted to force me to sign on a blank piece of paper, and when I refused, that was when they started beating me. They were threatening me, saying, ‘You need to stop doing the union activities in the factory, why did you try and form the union.’”

Her experience was not unique, according to “Whoever Raises Their Head Suffers the Most: Workers’ Rights in Bangladesh’s Garment Factories.” HRW also has released a video with garment workers describing the attacks they face when they try to form unions.

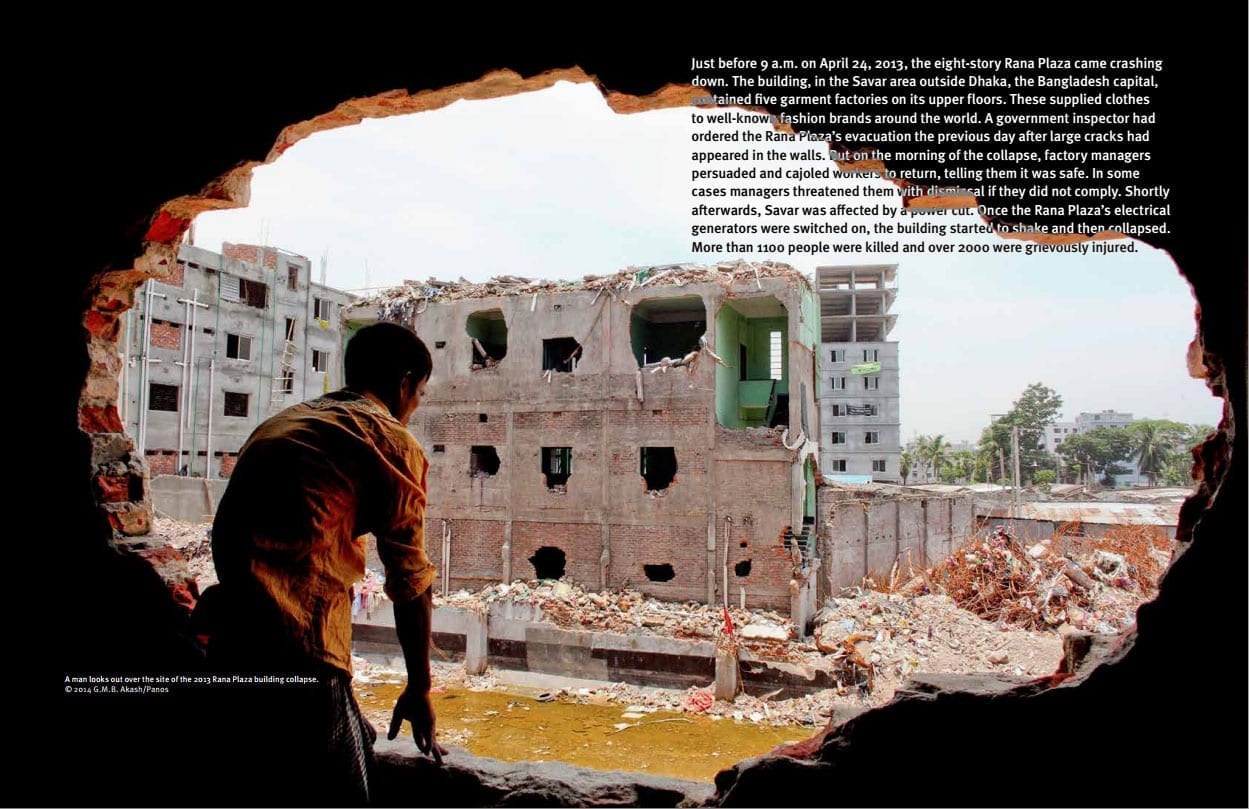

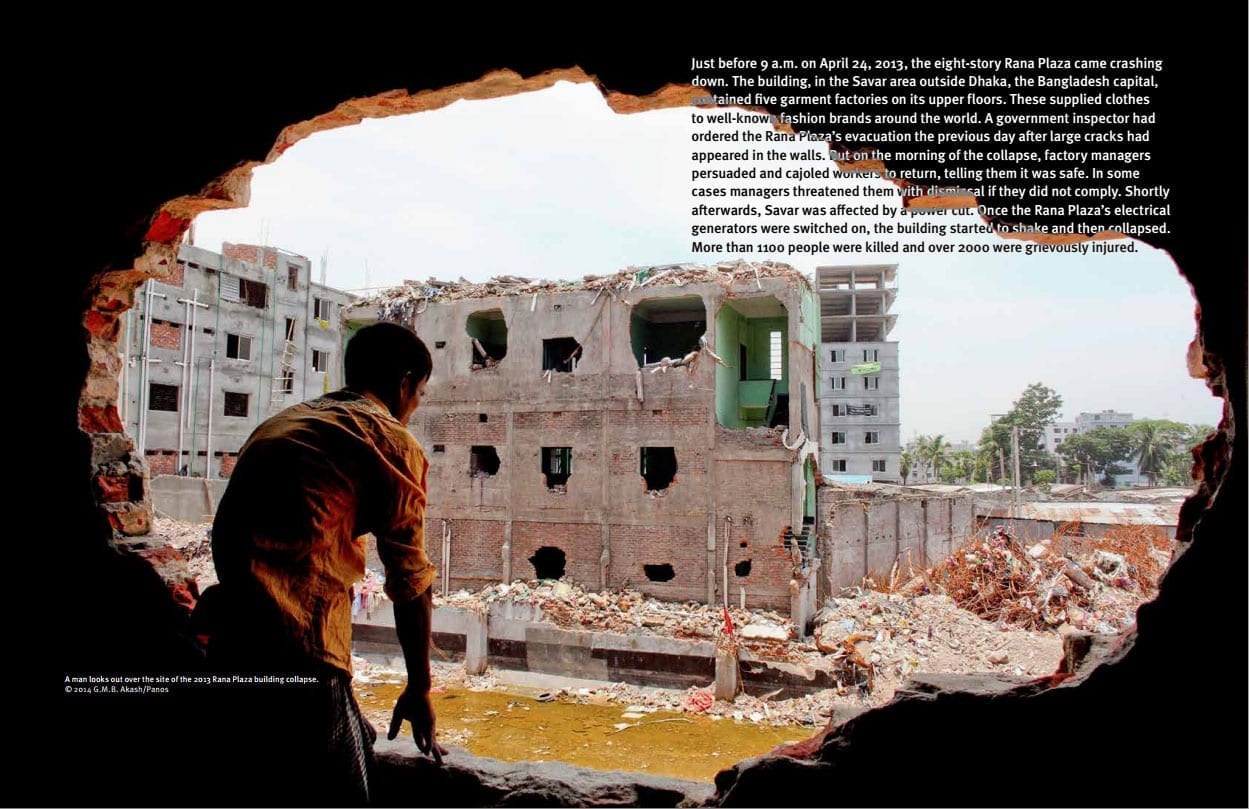

Two years after the deadly Rana Plaza collapse that killed more than 1,130 garment workers, the report finds that despite international outrage over the series of mass fatalities at Bangladesh garment factories in recent years, garment workers take great personal risk when trying to improve workplace conditions.

In providing an in-depth look at the experiences of more than 160 workers from 44 factories, the report concludes that “the primary responsibility for protecting the rights of workers rests with the Bangladesh government.

“The poor and abusive working conditions in Bangladesh’s garment factories are not simply the work of a few rogue factory owners willing to break the law. They are the product of continuing government failures to enforce labor rights, hold violators accountable and ensure that affected workers have access to appropriate remedies.”

Rigorous enforcement of existing law would go a long way toward ending impunity for employers who harass and intimidate both workers and local trade unionists seeking to exercise their right to organize and collectively bargain, according to the report.

“If Bangladesh wants to avoid another Rana Plaza disaster, it needs to effectively enforce its labor law and ensure that garment workers enjoy the right to voice their concerns about safety and working conditions without fear of retaliation or dismissal,” says Phil Robertson, HRW’s Asia deputy director.

The report also notes the lack of full financing for the Rana Plaza compensation fund, stating that it “should not be seen as a success or a model unless and until it is replenished and full compensation is paid to claimants.”

Among the report’s recommendations:

- The Bangladesh government should carry out effective and impartial investigations into all workers’ allegations of mistreatment, including beatings, threats and other abuses, and prosecute those responsible.

- The Bangladesh government should revise its labor law to ensure it is in line with international labor standards.

- Companies sourcing from Bangladesh factories should institute regular factory inspections to ensure that factories comply with companies’ codes of conduct and Bangladesh labor law.

Apr 16, 2015

In the hours and days after the multistory Rana Plaza building collapsed in 2013, killing more than 1,100 garment workers in Bangladesh, Solidarity Center Senior Program Officer Lily Gomes was an ever-present figure in the hospitals, where she went from bed to bed checking on injured workers and offering support. She also visited workers at their homes, to offer assistance and to document details of the world’s deadliest garment factory disaster.

Lily Gomes has conducted hundreds of trainings for Bangladesh garment workers. Credit: Solidarity Center

Providing emergency aid is one of a multitude of duties Gomes has undertaken since joining the Solidarity Center’s Dhaka office in 1996. Trainer, union organizer, curriculum developer, gender specialist and financial program monitor—over the years, Gomes has carried out these roles and many more, earning a doctorate in sociology from Jadavpur University in India along the way. Now, she has a new title: Fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy in Washington, D.C.

“This is the time clearly to focus on women garment workers to have them in leading positions,” Gomes says of her plans while in residence. During her five month-long Reagan-Fascell fellowship, she will develop a gender policy guideline for advancing women’s leadership among trade unions within Bangladesh’s ready-made garment (RMG) industry. “This is the time for women to express their voices.”

She brings to the fellowship a rare range and depth of experience. Gomes was among Solidarity Center staff aiding garment workers forming their first women-led union in 1996. “I was with them day and night,” she says, recounting the long hours involved in creating the Bangladesh Independent Garment Workers Union Federation (BIGUF), a milestone achievement not only for worker rights but one that “initiated the idea that women should be the main leadership to reflect the workers in the RMG industry in Bangladesh.”

Lily Gomes (front, left) and Bangladesh garment workers met with then-U.S. Rep. George Miller in 2013 about factory working conditions. Credit: Solidarity Center

In those years, child labor was rampant, and Gomes describes how factory owners would hide children in boxes or even toilets when inspectors arrived. Passage of the Child Labor Deterrence Act of 1999, long championed by former Sen. Tom Harkin, “was a huge thing for Bangladesh that assisted in complete elimination of child labor from the sector at the time,” Gomes says. The bill bans the importation to the United States of products that are manufactured or mined with child labor.

Following the law’s passage, Gomes helped the Solidarity Center set up and run schools for former child laborers “with a unique curriculum to address their needs,” a project that continued through 2002.

“The children were happy,” Gomes recalls. “They started relaxing. They learned not only academics but social issues,” including health and hygiene.

Gomes was coordinator of Solidarity Center-sponsored health clinics offering primary medical care for garment workers and their families. Over the years, she has provided workers with training sessions on topics as varied as labor law, financial management and collective bargaining negotiations. She also conducts fire safety training, a program the Solidarity Center pioneered for garment factory workers in 2000. In addition to helping garment workers unionize, she has assisted shrimp workers to organize and exercise their rights in seafood processing factories in southwestern Bangladesh.

Now, much of her focus is on empowering women garment workers to take on leadership roles and understand their rights to better advocate for themselves and their families. Although women comprise more than 90 percent of garment factory workers, during negotiations at unionized plants, “Women’s issues are sidelined in negotiations,” Gomes says.

“For instance, like ensuring contract language that includes breaks for breast-feeding and special care for pregnant women.” Women also have less access to better paying jobs and supervisory positions, outcomes generated by “socially built gender discrimination.”

In 2000, Gomes administered four Solidarity Center-sponsored Working Women Education Centers, where lawyers trained female factory workers on their rights regarding sexual harassment at the workplace, family leave and other issues important to women. Since then, she has reached hundreds of women workers through trainings on women’s labor rights and gender equality.

“Now, many of these Solidarity Center-trained women are leaders of other union federations,” Gomes says. “It’s a great feeling to know I trained them.”

In the late 2000s, she commuted for several years to India’s West Bengal state, to work on her Ph.D., which focused on the impact of employment and earning opportunities on female workers in Bangladesh’s RMG sector.

Beyond her organizational skills, educational background and talent for expertly taking on a broad range of tasks, Gomes brings to her work a compassion and deep understanding of humanity that sets her apart.

Recalling the hours after the Rana Plaza disaster, she describes visiting a school where bodies, nearly all young women, were laid out in row after row.

“I touched their hands and feet,” she said, “and felt like they were my sisters.”

Apr 6, 2015

Three years after the torture and murder of garment worker union leader Aminul Islam, his killers have not been brought to justice.

No one has been prosecuted for the torture and murder of garment worker union leader Aminul Islam.

The AFL-CIO and eight other global global labor rights organizations have written to Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina on the anniversary of his murder to demand his killers be located and prosecuted.

Aminul, 39, disappeared on April 4, 2012, and his body was found a few days later with signs of torture. He was a plant-level union leader at an export processing zone in Bangladesh, an organizer for the Bangladesh Center for Workers’ Solidarity (BCWS), and president of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation’s (BGIWF) local committee in the Savar and Ashulia areas of Dhaka.

Despite international outcry, including a U.S. congressional hearing and then U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s call for justice in the case, Aminul’s murder has gone unsolved. He had sought to improve the working conditions of some 8,000 garment workers employed by Shanta Group, a garment manufacturer based in Dhaka.

After the United States revoked preferential trade benefits for Bangladesh in 2013, citing human and labor rights abuses, the Bangladesh government dropped criminal charges against two garment worker leaders who worked with him, and announced it would step up the search for the people responsible for his torture and murder. Instead, the government dropped an investigation against a suspect and has taken no further steps to resolve the case.

“A sewing machine and a dozen colorful threads still give hope and strength to labor leader Aminul Islam’s family” but his widowed wife, Husne Ara, works around the clock to pay for food and school tuition for her children, writes the Bangladesh Daily Star.

Husne Ara said that Aminul could not speak over the phone because “he feared it was tapped.

“Even in the middle of the night, he received arbitrary phone calls from the intelligence,” she says.

Since Aminul’s murder, more than 1,200 garment workers were killed in the 2012 Tazreen factory fire and the 2013 collapse of Rana Plaza. After Rana Plaza, at least 44 workers have died in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh, and more than 900 people have been injured.

Jan 27, 2015

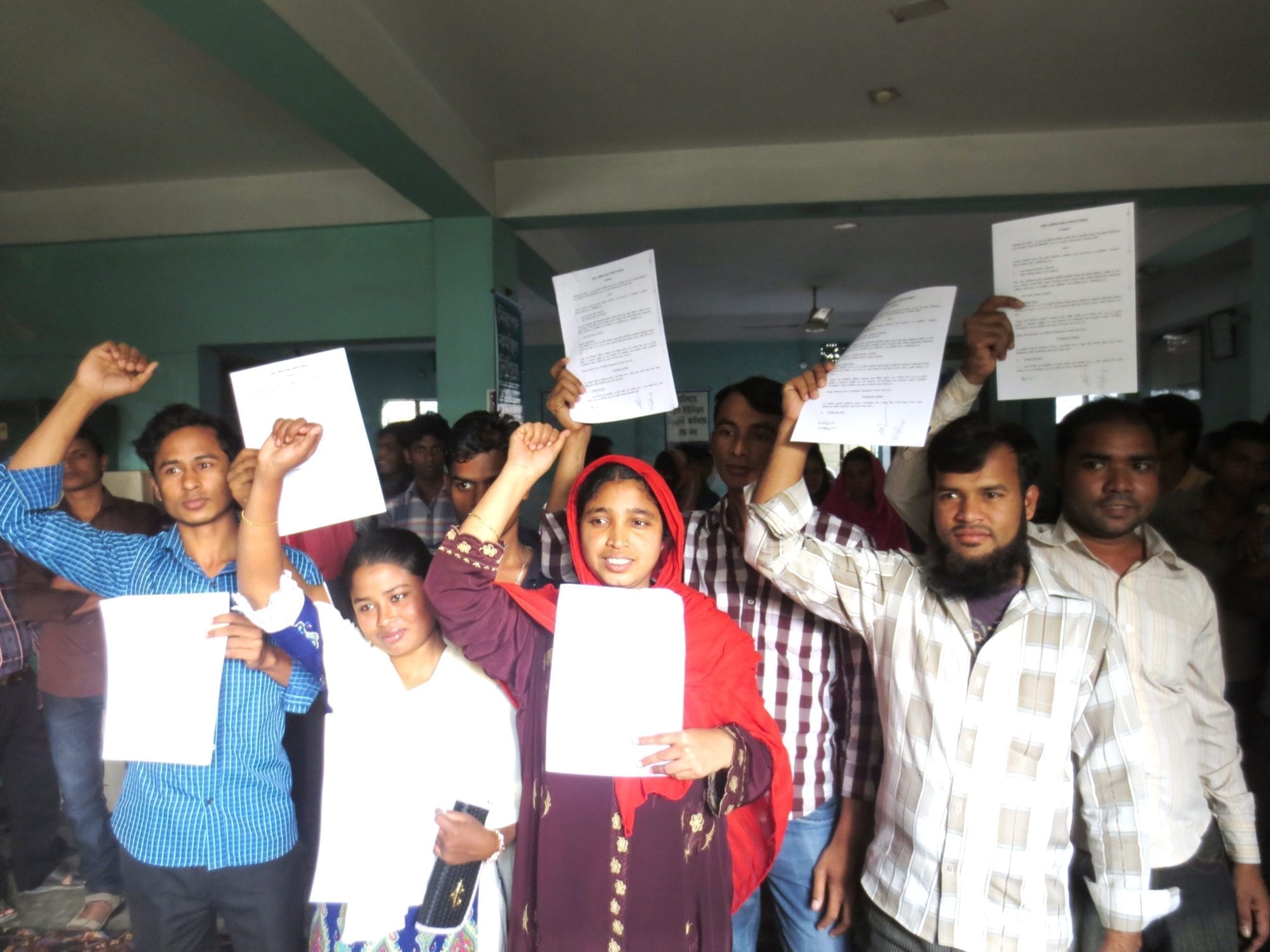

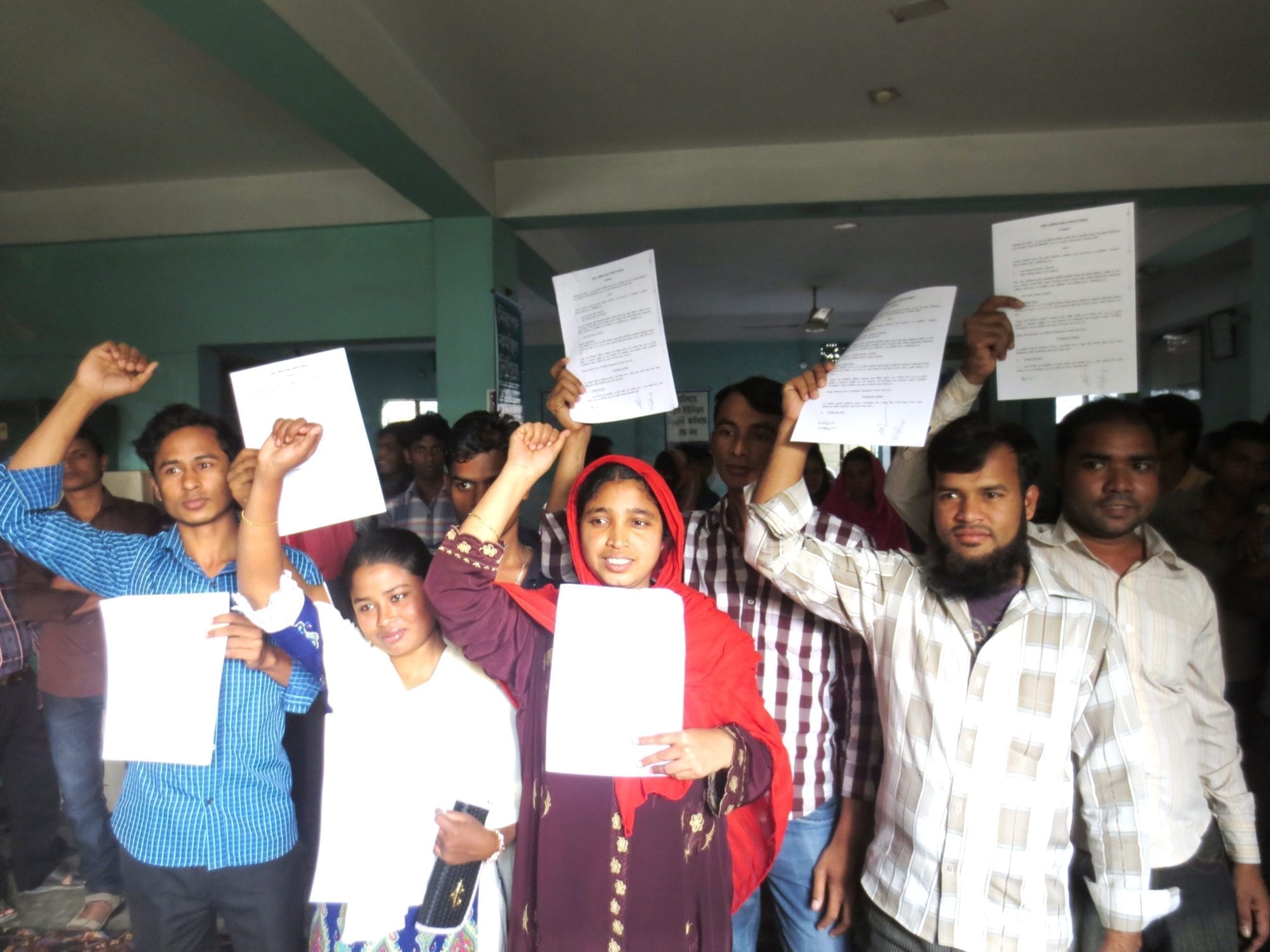

Standing strong in the face of a long and difficult struggle for their rights, Bangladesh garment union leaders at five factories in the East-West Industrial Park Ltd. group negotiated collective bargaining agreements in recent days that include increases in the food allowance, improvements in canteen facilities and provisions for union leaders to assist members.

The five union factories are affiliated with the Bangladesh Independent Garment Workers Union Federation (BIGUF), which helped negotiate an earlier agreement in May 2014 to resolve hostilities and lay the groundwork for good-faith bargaining. The Solidarity Center provided legal and other technical assistance to workers throughout the process.

Hamidul Islam, general secretary of the Rumana Fashion Ltd. Workers Union, which represents workers at one of factories in the group, said that despite the challenges leading up to the victory, “This is really just a starting point (for our union). We will be able to help workers the most if we can continue to discuss with the management about how to create a better working environment.”

Further, he said, “the days would have been harder and longer had it not been for the help of BIGUF and the Solidarity Center. It is still hard to believe that we are one of the few factories that have a signed collective bargaining agreement in the country’s entire garment industry. But we know it’s because we are strong and stuck together.”

Shahera, general secretary of Fashion Suit & Trousers Ltd. who was also involved in negotiations, said, “A union is about workers claiming their rights by being together, and I want to encourage other unions not to give up.”

However, workers who formed unions at five other factories in the group are still working to gain legal recognition by authorities.

“We are very encouraged by the progress that’s been made at the East-West group and will help the union leaders now work to implement the collective bargaining agreements in the factories,” said Raju, BIGUF acting general secretary.

“However, we continue to be concerned about the trade union registration process and that workers who have worked hard to organize their factories are having their unions unfairly rejected by the government.”

Dec 10, 2014

Each year on December 10, the global community marks International Human Rights Day, anchored in the founding document of the United Nations which asserts that each one of us, everywhere, at all times is entitled to the full range of human rights.

That founding document, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, also lists “the right to form and to join trade unions” as a basic tenet of human freedom. For many workers around the world, the right to form unions is essential for ensuring the safe working conditions and living wages that are fundamental to human rights.

Two years ago, on November 24, the devastating fire at the Tazreen Fashion Ltd. garment factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killed 118 workers, the majority of them young women. Commentators at the time compared the disaster to the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in New York, noting that moment in American labor history when young women garment workers began organizing their first unions.

The same phenomenon is taking root in Bangladesh, and for the same reasons. The momentum for union formation was accelerated by the April 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh, which killed more than 1,100 workers. Following these twin tragedies, workers, primarily women, formed more than 200 new garment unions. Their rapid formation has been driven by the determination of women workers who have experienced how the past 30 years of job creation has not led to their economic or social advancement. They seized the moment to collectively join together to demand that jobs offer more than a meager paycheck.

It has been a nostrum of development economics for the past 20-plus years that merely creating garment-sector jobs was the key to women’s liberation and empowerment. True, approximately 80 percent of workers employed in the Bangladesh’s garment sector are women. True, millions of women now have an independent means of earning an income, which is important to raising women’s status within their family and community.

However, few adherents to this economic analysis have examined whether creating low-wage jobs has truly led to women’s empowerment in a way that is personal, cultural, sustaining or lasting. Rather, many economists and political scientists view Bangladesh and the global garment supply chain through a purely free-market perspective. Through this lens, any wages at all enable women to improve their status. Yet it is much more difficult to acknowledge that the real issue is the global supply chain within which women need to exert their power and genuinely take control of their own destinies inside and outside the home.

Statistical evidence suggests that women toiling at the bottom of the global garment supply chain in Bangladesh do, in fact, experience some social changes in contrast to women working in a subsistence agrarian economy. Research shows that a 10-hour-a-day, six-days-a-week job in the Bangladesh garment industry may improve women workers’ chances to send their children to school and keep them in there longer. However, these arguments are oversold. Women garment workers may or may not control their wages, depending upon gender-based power relations inside their homes. Often, they do not favor women.

Over the past 17 years that I have been involved with the Bangladesh labor movement, I have repeatedly seen how an income does not guarantee independence for a woman garment worker. This anecdotal evidence is backed up by fact. Research suggests that girls age 17 and 18 years old who live near garment factories actually drop out of school at a higher rate than their rural counterparts who go to work in the industry. Further, a 2009 study by the Bangladesh government’s National Bureau of Economic Research documents that non-garment workers’ mothers had a higher level of education than those of garment workers. And farm labor actually pays more than a job at a garment factory in the high-cost, high-inflation environments of Dhaka or Chittagong, according to a recent article in Dhaka’s Financial Express.

So if the one-dimensional argument that earning a wage results in women’s empowerment is fiction, what is the manifestation of real progress for women?

For the answer, I would point to prominent labor activists who have risen from the factory floors and now are organizing among their peers.

Kalpona Akter, Nazma Akter (no relation) and Nomita Nath, for example, all worked as child laborers in garment factories. They have emerged as real leaders, not because they made poverty wages as teens but because they dedicated their lives to uplifting the status of women workers in their society. They have found their power in fighting for jobs that do not starve, maim or kill women. And they know that vulnerable workers find empowerment when they have a union to represent them.

Workers struggle every day on Bangladesh’s factory floors. Women report that physical and verbal abuse are a matter of course. They are threatened when they do not make a quota or when they get pregnant. Or worse. Mira Boashak, president of a local union in Dhaka, was severely beaten in August by several men who had staked out her garment factory.

Despite these challenges, a young organizer told me earlier this year in Dhaka that prior to recent tragedies, her efforts to organize women into unions made her community think she was a troublemaker. Now, she said, she is seen as a champion of women’s rights and looked up to as a leader.

Real women’s empowerment—realized through asserting fundamental human rights.