Apr 28, 2015

Garment workers practice emergency techniques during a Solidarity Center fire safety training. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Safe and healthy jobs are among workers’ most fundamental rights, and each year on April 28, World Day for Safety and Health at Work, the global labor community shines a spotlight on these rights. Workers and their unions commemorate those who lost their lives on the job and hold events and informational activities to raise awareness of the need for workers, employers and governments to actively participate in securing a safe and healthy working environment.

Through unions, workers achieve the strong, collective voice needed to improve safety and health at the workplace. In Bangladesh, where the deadly Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory fire killed 112 garment workers in 2012, and where at least 41 garment workers have perished in fire incidents since then, more and more workers are seeking unions to ensure their factories are safe.

In recent months, dozens of garment workers have taken part in the Solidarity Center’s fire safety training program, a 10-session course that aims to equip union leaders with essential knowledge and skills on workplace safety. The workers then educate their co-workers and strengthen their unions’ ability to raise and rectify unsafe factory working conditions.

“People who worked at Tazreen and Rana Plaza had no training and had no union,” says Saiful, referring to the Rana Plaza building collapse that killed more than 1,130 garment workers in 2013. “This training is about making sure those things never happen again.” Saiful, a union leader from Radisson Apparels, took part in the most recent fire safety training

Participants who successfully completed a fire safety training take part in a closing ceremony. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Urmi, a union organizer, agrees. “Thousands of people died (as a result of Rana Plaza and Tazreen). We need to know what to do and have, and give workers the confidence to be leaders in their factories.”

In the program’s next stage, the Solidarity Center and the union leaders who have participated in the training will begin training workers at their factories.

Morshed Hossain a union leader from Step III Apparels Ltd., says he organized a union at his factory so workers could push for clean toilets, respect from supervisors and their due wages. Morshed said that midway through the fire safety training in March, he went back to “talk to the other workers in my factory about what to do in case there is a fire.”

Abdul Hakim, a union organizer who also took part in a fire safety training, said “before this training, we were not aware about workplace safety. But now we know what to do and how we can talk to workers.”

As Solidarity Center Bangladesh Country Program Director Alonzo Suson said during a ceremony marking the conclusion of the first fire safety training last July:

“Workers around the world have found that, by forming unions and speaking with a collective voice, they are better able to ensure safer working conditions. These new union leaders will be able to take what they’ve learned back to their co-workers to make their factories better, healthier and safer places to work.”

Apr 27, 2015

With thousands of people dead and even more made homeless in Nepal following a devastating magnitude-7.8 earthquake, Solidarity Center union allies in the country are reporting no casualties among their staff and are organizing to support relief efforts in the Nepali capital.

The General Federation of Nepalese Trade Unions (GEFONT), which represents mostly blue-collar workers, the Nepal Trade Union Congress (NTUC), which includes teachers and other white-collar workers and the Joint Trade Union Coordination Center (JTUCC), the umbrella organization of GEFONT and the NTUC, say their employees are safe and now working to provide disaster relief. Both GEFONT and the NTUC represent many workers in the tourist industry.

“Kathmandu valley is unimaginably destroyed,” says Bishnu Rimal, GEFONT president. “It is the most terrible quake we have ever experienced. Chilling cold, plus rain, lack of tents and [continuous] jolts is sufficient to scare people. It has disturbed even rescue work.”

The earthquake hit central Nepal on Saturday, from Mount Everest to Kathmandu and further west, wiping out entire villages. As rescue teams began to arrive from around the world, much of the stricken area remained inaccessible, locked in mountainous terrain with some roads blocked by landslides.

In letters to Rimal and Khila Dahal, NTUC general secretary, AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka expressed heartfelt condolences and solidarity.

“We will … work with the global labor movement to ensure that the working families impacted by this tragedy receive the support needed to rebuild their communities,” Trumka said.

The earthquake and aftershocks were felt as far away as Dhaka, Bangladesh, where one garment worker was killed and more than 200 injured as workers rushed out of factories when the quake hit.

At least one worker reported to Solidarity Center staff there that he took successful safety measures at his factory when the quake hit because of skills he learned at a recent Solidarity Center’s fire and building safety training. In recent months, the Solidarity Center has held a series of safety trainings for garment workers near Dhaka and Chittagong, where most factories are located. The 10-day trainings provide workers with hands-on fire and building safety experience, which includes steps to take during earthquakes.

Apr 22, 2015

Rabbi, 10, lost his mother in the Rana Plaza collapse. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

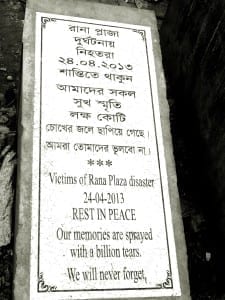

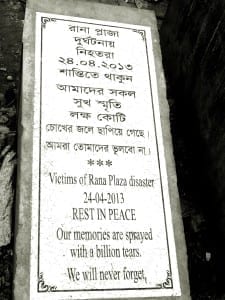

Rabbi Sheikh, 10, began crying when talking about his mother, Shirina Akhter. “I always think about my mother,” he said. Two years ago, Shirina was among more than 1,130 garment workers killed when the multistory Rana Plaza building pancaked. Her husband, Latif Sheikh, heard the building collapse as he sold fruit by the roadside. It took him 17 days to find Shirina’s body.

“My son always cries, remembering his mother,” Latif says. “He is not able to lead a normal life like the others at his age.”

As the global community commemorates the April 24 Rana Plaza tragedy, thousands of garment workers who survived the disaster, mostly young women, remain too injured or ill to work, and the families of those killed struggle emotionally and financially to piece together the lives shattered that day.

Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka recently spoke with survivors and the families of those who lost loved ones in the collapse, and all say they are struggling to make ends meet, unable to pay rent, send their children to school or provide for other basic needs.

International labor organizations and prominent retailers created a $30 million compensation fund in 2013 to aid families of workers killed and injured at Rana Plaza. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), 75 percent of those who sought compensation have received something, but to date, 5,000 people have received only 40 percent of the money due them. Further payments have been delayed because clothing brands have failed to pay the $9 million needed to cover claims. (Download a fact sheet here.)

Bangladesh’s $24 billion garment industry is the world’s second largest, after China, and some 80 percent of Bangladesh’s garment exports are destined for the United States and Europe.

Despite constant pain from her injuries at Rana Plaza, Kohinoor, a single mother, is forced to work to support her children. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Kohinoor is among the luckier Rana Plaza survivors. A single mother, she worked as an assistant at Phantom Apparels, one of five factories in the Rana Plaza building. She received some compensation from several sources, including $625 from the ILO and $562 from Primark, which enabled her to pay her medical bills and support her three children for nine months while she was treated for the injuries she sustained.

Despite constant pain, she works as a cleaner in three homes, but her wages are not sufficient to support school fees, and so her children cannot attend school. Her eldest son helps the family by working in a restaurant.

“Nowadays, I have to be absent regularly from my work, as I don’t find the proper strength to work,” she said. Like all those Solidarity Center staff talked with, Kohinoor would like to be fairly compensated so she can support her family.

Standing in the rubble of Rana Plaza, Mosammat Mukti Khatun describes how her injures at Rana Plaza have made it impossible to adequately support her family. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Mosammat Mukti Khatun, 27, was rescued after spending nine hours in the darkness, pinned in the debris of collapsed cement. She also used all of the compensation she received for medical bills and to support her family while she was recovering. Mosammat still suffers from acute pain, and recently suffered additional injuries at a garment factory where she began working in January. Her husband, a day laborer, makes little money, and with five children, the family is in debt.

“I have no money left to secure my days,” Mosammat says. “I do not know how we will get by without additional support.”

On April 24, garment workers and their families plan to form a human chain at the national press club in Dhaka, before placing flowers at the Rana Plaza site.

Apr 21, 2015

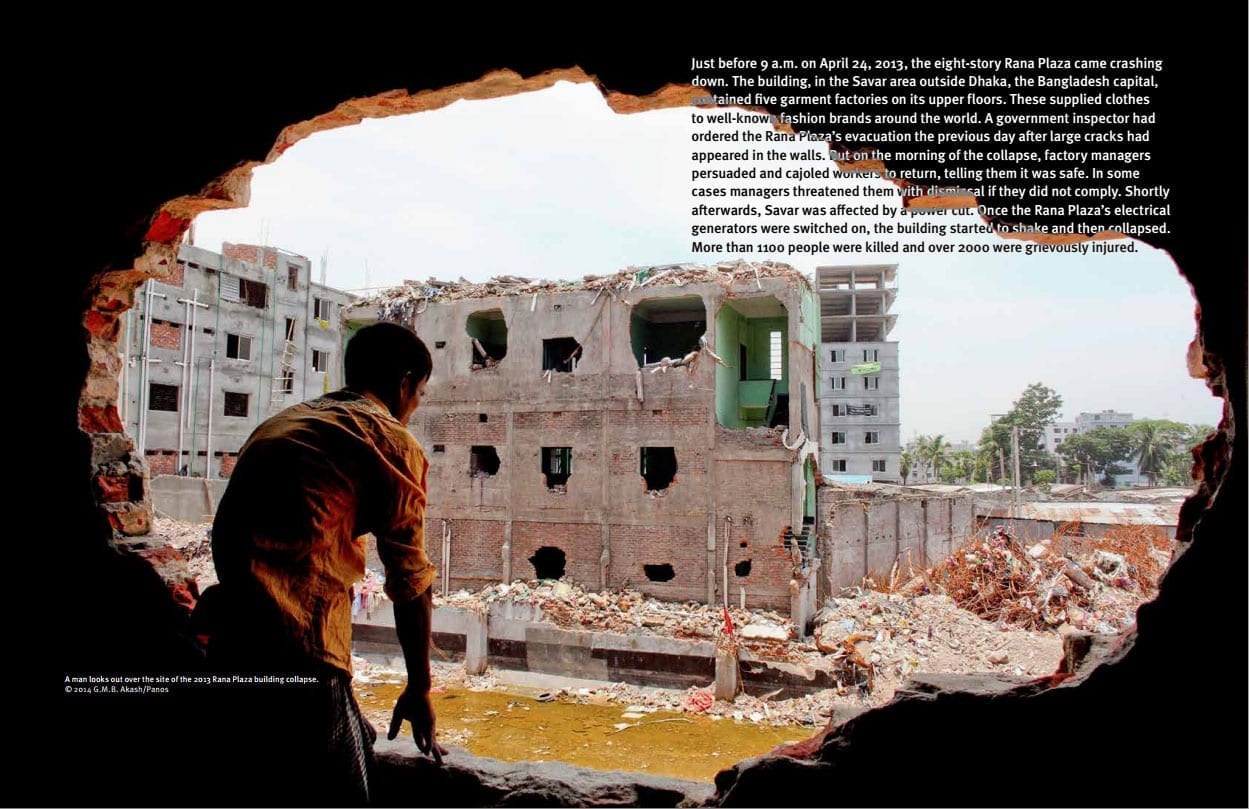

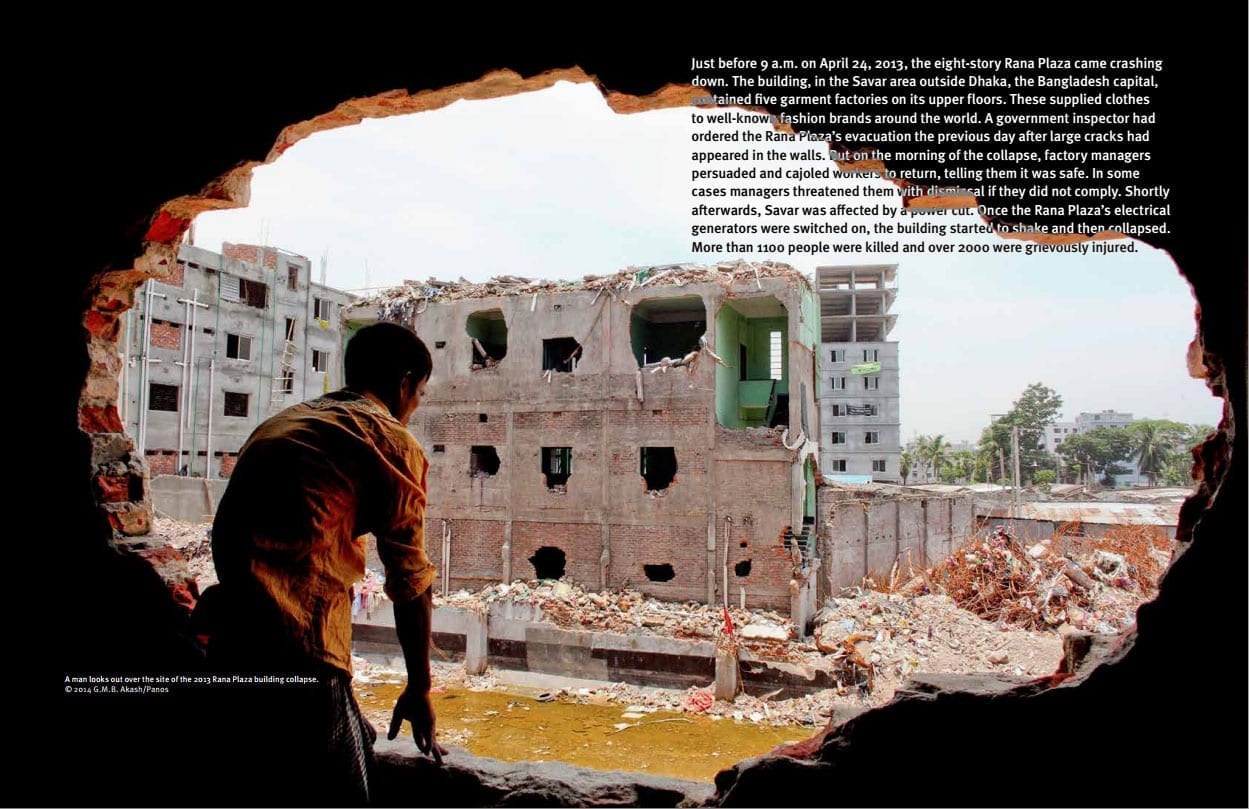

In the initial months after the Rana Plaza collapse on April 24, 2013, a preventable catastrophe that killed more than 1,130 Bangladesh garment workers and injured thousands more, global outrage spurred much-needed changes.

The site of the Rana Plaza building two years after it collapsed. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Dozens of garment factories were closed for safety violations through the Bangladesh Fire and Building Safety Accord process, a legally binding agreement in which nearly 200 corporate clothing brands pay for garment factory inspections. Other inspected factories where problems were identified have addressed pressing safety issues. Workers organized and formed unions to address safety problems and low wages—and the government accepted union registrations with increasing frequency—after the United States suspended its Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) agreement with Bangladesh based upon chronic and severe labor rights violations.

But in recent months, those freedoms are increasingly rare, say garment workers and union leaders.

“After the Rana Plaza and Tazreen disasters, it had become easier to form unions,” says Aleya Akter, president of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF). But since November 2014, the government is more frequently rejecting registrations, she said, speaking through a translator while at the Solidarity Center in Washington, D.C., this week. The Tazreen Fashions factory fire five months before the Rana Plaza collapse killed 112 garment workers. (Download a fact sheet here.)

Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Overall government rejections of unions that applied for registration increased from 19 percent in 2013 to 56 percent so far in 2015, according to data compiled by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the Bangladesh capital. Despite garment workers’ desire to join a union, they increasingly face barriers to do so, including employer intimidation, threatened or actual physical violence, loss of jobs and government-imposed barriers to registration. Regulators also seem unwilling to penalize employers for unfair labor practices.

“In our view, a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry,” according to a March International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) report. “The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.”

Meanwhile, thousands of workers still toil in unsafe factories. In the two years since the Tazreen fire, at least 31 workers have died in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh, and more than 900 people have been injured (excluding Rana Plaza), according to Solidarity Center data. The Accord and the non-legally binding Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety have nearly completed their inspections, which will total fewer than half of the country’s 5,000 garment factories, including 600 factories that have refused entry to inspectors, according to the International Labor Organization.

In recent months, the Solidarity Center has conducted a series of fire safety trainings for garment workers near Dhaka and Chittagong, where most garment factories are located. The 10-day trainings provide workers with hands-on fire and building safety experience.

Following one recent training, Lima, a factory-level union leader, says she “learned a lot.

“We organized our union in mid–2014. The staircase that workers use in my factory used to be blocked and was a fire hazard. But through our union we took the initiative to talk to management about the problem and now the staircase is clear.”

When garment workers like Lima are allowed to form unions, they have the opportunity to create positive changes at their workplaces, making unions fundamental to substantive improvements in Bangladesh garment factories—an opportunity fewer and fewer garment workers can grasp in the current environment.

Apr 20, 2015

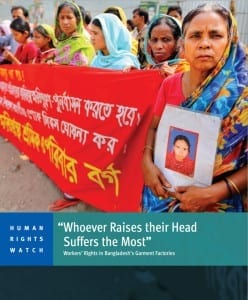

Bangladesh garment workers often risk their health and their lives at unsafe factories, and when they seek to form unions to address workplace problems, “factory managers continue to use threats, violent attacks and involuntary dismissals in efforts to stop unions from being registered,” according to a Human Rights Watch report released today.

“I was beaten with metal curtain rods in February when I was pregnant,” one garment worker told HRW. “They wanted to force me to sign on a blank piece of paper, and when I refused, that was when they started beating me. They were threatening me, saying, ‘You need to stop doing the union activities in the factory, why did you try and form the union.’”

Her experience was not unique, according to “Whoever Raises Their Head Suffers the Most: Workers’ Rights in Bangladesh’s Garment Factories.” HRW also has released a video with garment workers describing the attacks they face when they try to form unions.

Two years after the deadly Rana Plaza collapse that killed more than 1,130 garment workers, the report finds that despite international outrage over the series of mass fatalities at Bangladesh garment factories in recent years, garment workers take great personal risk when trying to improve workplace conditions.

In providing an in-depth look at the experiences of more than 160 workers from 44 factories, the report concludes that “the primary responsibility for protecting the rights of workers rests with the Bangladesh government.

“The poor and abusive working conditions in Bangladesh’s garment factories are not simply the work of a few rogue factory owners willing to break the law. They are the product of continuing government failures to enforce labor rights, hold violators accountable and ensure that affected workers have access to appropriate remedies.”

Rigorous enforcement of existing law would go a long way toward ending impunity for employers who harass and intimidate both workers and local trade unionists seeking to exercise their right to organize and collectively bargain, according to the report.

“If Bangladesh wants to avoid another Rana Plaza disaster, it needs to effectively enforce its labor law and ensure that garment workers enjoy the right to voice their concerns about safety and working conditions without fear of retaliation or dismissal,” says Phil Robertson, HRW’s Asia deputy director.

The report also notes the lack of full financing for the Rana Plaza compensation fund, stating that it “should not be seen as a success or a model unless and until it is replenished and full compensation is paid to claimants.”

Among the report’s recommendations:

- The Bangladesh government should carry out effective and impartial investigations into all workers’ allegations of mistreatment, including beatings, threats and other abuses, and prosecute those responsible.

- The Bangladesh government should revise its labor law to ensure it is in line with international labor standards.

- Companies sourcing from Bangladesh factories should institute regular factory inspections to ensure that factories comply with companies’ codes of conduct and Bangladesh labor law.