Dec 8, 2021

A new report by the Nigeria Labor Congress (NLC) and the Solidarity Center, “Breaking the Silence: Gender-Based Violence in Nigeria’s World of Work,” finds that gender-based violence and harassment (GVBH) at work is widespread in Nigeria, but goes largely unreported. The report looks at the pervasiveness of GVBH in Nigeria—which boasts Africa’s largest economy, the continent’s biggest trade union movement, and a growing population of 200 million.

A lack of worker-led research about the scope and incidence of GBVH in Nigeria’s world of work, poor implementation and enforcement of laws and workplace policies, entrenched discriminatory gender norms, and an inadequate legal framework hampered civil society and union efforts to address the problem. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these dynamics, exposing many workers, particularly women and other marginalized workers, to an even higher risk of GBVH.

The NLC and the Solidarity Center partnered to address the lack of data on GBVH in the world of work. The NLC established a women and youth structure known as the National Women Commission in September 2003, which works with NLC affiliates and stakeholders to promote gender equality and empower women and youth to take on leadership positions. It facilitates programs that address GBVH at work.

Through this structure, women workers successfully campaigned for the NLC sexual harassment policy. This victory paved the way for women to play a leading role in the adoption of the International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention 190 (C190)—the first global, binding treaty that recognizes the fundamental right to a workplace free from violence and harassment, including GBVH.

Assault In Lagos Market

A recent incident of alleged GBVH shows the importance of this work. Earlier this month, a magistrate court recommended prosecution for a man accused of sexually assaulting a minor in an open market in Lagos. The International Lawyers Assisting Workers (ILAW) network, a project of the Solidarity Center and now the largest global network of workers’ rights lawyers and advocates, is assisting with the case.

The court’s recommendation is a direct result of awareness training with market vendors about their right to GBVH-free workplaces. Following the ILO’s adoption of C190 in 2019, the NLC and the Solidarity Center began training workers to put into practice provisions preventing GBVH. A newly formed GBVH task force in the market brought attention to the alleged assault, leading to a trial in Nigeria’s high court.

Breaking The Silence

The report results from efforts by women workers to provide concrete evidence regarding the scope and incidence of GBVH at work and break the silence to tell their stories of strength and courage.

Women workers identified two locations for study in Abuja and Lagos. Then, they drafted questions and conducted one-on-one interviews with peers. In the first stage—from September 7, 2020, to October 29, 2020—researchers interviewed 425 women. During the second stage—from December 7, 2020, to February 26, 2021—researchers 494 women. In total, women workers interviewed 919 of their peers and captured data across eight sectors, including the informal economy, manufacturing, healthcare, education, construction, media, hospitality and the public sector.

Behind these numbers are women workers like Amina,* an office cleaner who says she was sexually assaulted by a supervisor and was laid off by her employer. Saraya, a market porter, says she experienced groping and inappropriate touching while commuting to and from work and sexual harassment on the job.

Magdalene, a quality inspector at a bottling company, says she was sexually harassed and sexually assaulted by her supervisors. “I find that the joy that comes with going to work every day is no more there,” she said.

Ada has co-owned a bar with her husband. His domestic violence in their marriage extends to her workplace. “I have never reported to anyone. You are the first person I am sharing this with,” she told an interviewer.

An anonymous male youth trader spoke of the need for more training on GBVH. “We need training on GBVH for men in our market,” he said. “I believe that trainings will go a long way in sensitizing men on the negative impact of GBVH on the lives of women and children.”

Regina Otorkpa, who interviewed women workers, says, “GBVH is a monster silently destroying the confidence and future of survivors still struggling to speak out due to fear of society, fear of self and discrimination.

“Having interacted with survivors of the different forms of GBVH in Nigeria’s world of work, it has become important for the Nigerian government to step up and take a bold step towards C190 ratification. I urge women to be brave and courageous to unmask their fears; it is important that we stop the stigmatization; the struggle against GBVH is a collective one for the good of all.”

Findings and Recommendations

The report unveils high rates of GBVH at work, which goes largely unreported. Findings include:

- More than half (57.5 percent) of women workers interviewed said they experienced GBVH in the world of work.

- Nearly 44 percent said their supervisor or superior had said or done something that made them uneasy due to their gender.

- Only 19.6 percent said they reported incidents of GBVH at work.

- More than one-third (35.9 percent) said they rarely received justice even when they reported violations.

- Some 44 percent said they had suffered gender discrimination that affected their career advancement.

- Nearly one-third (28.8 percent) said they were pressured for sexual favors at work and touched in ways that made them uncomfortable.

Based on this research, the NLC’s recommendations for unions, employers and the Nigerian government include:

- Increased education and awareness of GBVH among workers, managers and supervisors, the general public and policymakers, including its root causes and impacts and the responsibility of all workers to end it.

- Ratification and implementation of ILO Convention 190 concerning the elimination of violence and harassment in the world of work, including GBVH.

- Development of workplace policies to address GBVH and gender discrimination, including safe, confidential processes for reporting incidents; transparent processes for investigation of allegations; remedies for workers who experience GBVH; penalties for perpetrators; and changes to how work is organized to address power imbalances and other risk factors for GBVH in the world of work.

- Adoption of national legislation incorporating the definition of GBVH from ILO C190, protecting the entire world of work and covering all workers regardless of contractual status, including workers in the informal economy.

*All names are pseudonyms to protect the identities of women workers.

Aug 14, 2018

Gertrude Mtsweni and Rose Omamo, trade union leaders from Africa, recently joined hundreds of workers who participated with government and employer representatives in high-level deliberations on a draft global standard addressing gender-based violence at work.

Energized after long days of intense discussions during the International Labor Organization (ILO) conference in Geneva, the women are now working nonstop at the local and regional levels to educate union members about the draft convention and campaign to push their governments to ratify it after passage.

“All sectors—including clothing and textiles, food and service, transport—are involved in the campaign to end gender-based violence at work,” says Mtsweni, gender coordinator for the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU). Mtsweni is spearheading 16 days of action beginning November 25 in which workers from 16 sectors represented by the federation develop messages highlighting aspects of gender-based violence at work. November 25 is International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women.

COSATU was among unions joining the thousands of women and their allies who marched across South Africa August 1 to protest gender-based violence as part of the #TotalShutdown campaign. As a result, South Africa President Cyril Ramaphosa acknowledged that “South Africa has failed its women and their constitutional rights” and announced a national summit to address violence against children and women.

Moving Governments to Ratify the Convention

“Government should stand firm to say “No” to violence and harassment in the world of work”—Rose Omamo Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

In Kenya, Omamo is traveling around the country to educate engineers and workers in glass, metal and petroleum about the draft convention. Omamo is general secretary of the 11,000-member Amalgamated Union of Kenya Metal Workers, national chair of the Congress of Trade Unions–Kenya (COTU-K) Women’s Committee, and COTU-K executive board member.

She says workers are especially pleased that the draft convention, “Ending Violence and Harassment in the World of Work,” covers many groups, including women, men and young workers.

“Because violence in the workplace is rampant, they are saying this will help us have a firm stand to push government against violence at workplace, at home and in society.”

Omamo and Mtsweni also are working with the gender commission of the Organization of African Trade Union Unity (OATUU) to develop an effective message to urge their governments to ratify the convention after it is passed by the United Nations. Countries are not covered by a UN convention unless their governments ratify it and indicate they are committed to applying its provisions in national law and practice, and reporting on its application at regular intervals.

“One strong message we are putting across is that the government should stand firm to say “No” to violence and harassment in the world of work, and workers must be protected wherever they are,” says Omamo. The dozens of OATUU union affiliates are based in countries such as Angola, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea, Rwanda, Tanzania and Togo, in addition to Kenya and South Africa.

Unions’ Campaign for Convention on Gender-Based Violence at Work

The Solidarity Center produced a video as part of its campaign for passage of a gender-based violence at work convention.

Momentum for an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work follows years of advocacy by the global union movement, an effort led by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC).

Leading up to the most recent negotiations, Solidarity Center partners urged their unions, governments and employers to publicly support a binding ILO convention on violence and harassment at work that includes gender-based violence.

With Solidarity Center support, more than a dozen workers—from Brazil, Cambodia, Gambia, Guatemala, Honduras, Indonesia, Kenya, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, Palestine, South Africa, Swaziland, Tunisia and Zimbabwe—participated in the ILO conference. Several took lead roles in the negotiations as part of the workers’ group, including Omamo, who ensured gender-based violence remained the focus of discussions.

“The workers were very strong in negotiations, very specific on what they want,” says Omamo. “They took a very firm stand on the areas they felt that were good for workers.”

Elsewhere, union members from Ghana, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Turkey joined their sisters from across Nigeria in a weeklong training on the ILO draft convention, sponsored by the National Women Commission’s of the Nigerian Labor Congress (NLC).

And in Honduras, Solidarity Center staff organized a meeting of representatives from unions, government and business to garner support for a global standard inclusive of gender-based violence and to advocate for a law on sexual harassment at work.

The ILO in recent days released an updated version of the draft convention that reflects the discussions this spring, and will hold follow-up meetings throughout the fall. The organization will issue a second questionnaire for unions, governments and business to solicit further input on the convention (the results of the first questionnaire were incorporated in a draft last spring), and final discussion will take place at the next full ILO conference next May.

Sep 26, 2017

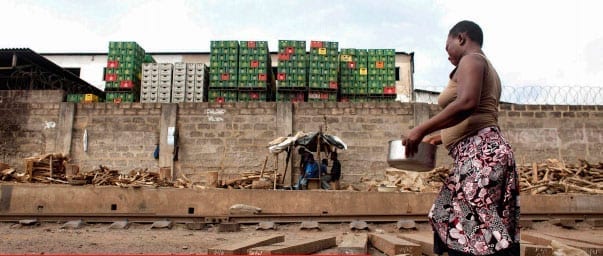

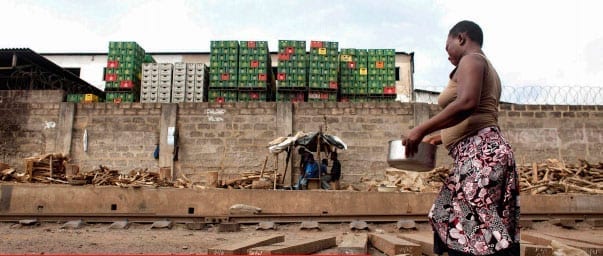

In the photo, a Ghanaian street vendor sells her wares in front of a massive multinational brewing company.

Guess who pays more in taxes?

The image, an ActionAid photo, shows the inequity of an impoverished vendor paying more in taxes than a major multinational, and makes concrete the reality of illicit financial flows for millions of Africans.

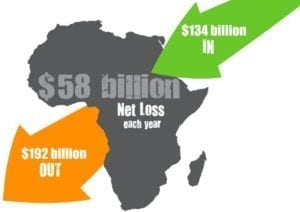

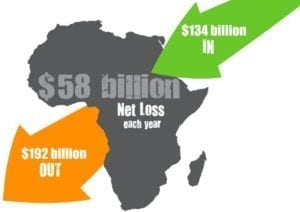

Africa loses at least $50 billion annually, likely much more, through illicit financial outflows, an amount equal to the development assistance it receives each year. Meanwhile, the number of people living on less than $1.25 a day is estimated to have increased from 290 million in 1990 to 414 million in 2010, according to a report commissioned by former South African President Thabo Mbeki. The report defines illicit financial flows as “money illegally earned, transferred or used.” The definition also encompasses the socially undesirable, such as the multinational corporate tax avoidance.

“The problem with IFFs in Africa is that money flows out of Africa and it never flows back,” says Luckystar Miyandazi, policy officer in the African Institutions Program at the European Center for Development Policy Management (ECDPM).

“When illicit financial flows happen, especially in Africa, there is a deficit of taxes,” she says. “Governments find ways of raising this money because they still need money to run, so that means increases in basic goods and services. [Higher] taxes on food, milk and so on affects workers, the community.”

Such regressive tax policies disproportionately harm informal workers and people living in poverty—the majority of whom are women.

Africa Delegation Travels US to Discuss Illegal Financial Flows

“The nature of investment we see that comes to Africa drives the race to the bottom”—Joel Odigie

Miyandazi is part of a four-person Solidarity Center delegation to the United States this month seeking to shine a light on the massive, yet little recognized crisis of illegal financial flows. The group spoke Monday at a panel on the University of California, Berkeley campus, and at a session sponsored by the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s Africa Braintrust in Washington, D.C., on Friday.

“The nature of investment we see that comes to Africa drives the race to the bottom,” says Joel Odigie, a member of the delegation and coordinator of Human and Trade Union Rights at the International Trade Union Confederation-Africa (ITUC-Africa). “There’s an attraction for financial direct investment, and business asks for benefits and concessions,” including lower labor standards, which drives down opportunities for good jobs. The result, says Odigie, is increasing numbers of working poor. (Odigie also spoke on the ITUC’s Radio Labor.)

“Work is on behalf of dignity—if you work, you get out of poverty,” he says. Yet “so many persons are working, breaking their backs, but they’re still in poverty.”

African trade unions and civil society organizations are leading this discussion and have responded with initiatives such as the launch of a transnational movement, Stop the Bleeding Africa, to educate around IFFs and mobilize citizens to advocate for corporate and government accountability.

African trade unions and civil society organizations are leading this discussion and have responded with initiatives such as the launch of a transnational movement, Stop the Bleeding Africa, to educate around IFFs and mobilize citizens to advocate for corporate and government accountability.

“For us the campaign around illicit financial flows is basically trying to make our members understand what the IFF is all about and bringing the message home—how this directly affects workers,” says Caroline Mugalla, executive secretary of the East Africa Trade Union Confederation (EATUC) and a delegation member. (Mugalla also spoke on the ITUC’s Radio Labor.)

Using Tanzania as an example, Mugalla says she points to the $4.8 billion Tanzania loses each year in illegal financial flows, and describes for people how that money could be used to improve the health delivery system and ensure children have access to education.

“Then people get it,” she says.

Going Forward

Mugalla says unions also are connecting with local government leaders to make the connection between the financial outflows and their struggle to provide basic services.

“A community has no water, no paved roads, no electricity—but the nearby mining company has it all,” she says.

When making tax policy, governments “need to take into account the people at the lowest level,” says Miyandazi. “For example, when a government gives a mining contract to a company and it’s going to displace people, governments should put people first and not multinationals.

The bottom line, says Miyandazi: “When making policy on Africa, Africa should be sitting at the table, part of the people who inform this policy and not be done by other people who think things should be done for Africa,” she says.

Gyekye Tanoh, team leader of the Policy Economy Unit at Third World Network Africa, also is taking part in the delegation.

Aug 24, 2017

As a young woman working in her company’s IT department, Jayne Muthoni Njoki was frustrated by what she says were employer attempts to push her around because of her youth and sex. But rather than quit her job, which she contemplated, she ran for a leadership position in her union, determined to work with others to make change on the job—and in society.

“I needed to fight for people whose voice can’t be heard,” she says.

Now 31, Njoki is the only young person in elected leadership in the Central Organization of Trade Unions–Kenya (COTU-Kenya), a Solidarity Center partner, and also president of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC)-Africa Young Workers Committee.

Njoki discussed how she is working through unions in Kenya and around Africa to educate and train young workers, especially young women, this week on the Working Life podcast, hosted by Jonathan Tasini (Njoki’s interview starts at 30:02).

Many Young Workers Work in Jobs that Don’t Pay Enough to Get by

With 71 million young people around the world unable to secure employment and 156 million more working poor because they have unstable income in the informal economy, the lack of jobs that pay living wages “is a global issue,” she says.

“We need to now think of the informal sector. When I talk of informal economy, that’s where you see the majority of young people are based.

“But unfortunately, we don’t think the informal sector is part of the economy.” Enabling informal-economy workers to have a voice through unions and associations is key to advancing their rights as workers—and once the informal economy is organized, “then everything will fall into place,” she says.

Through COTU-Kenya, which she says has encouraged young workers and women to become union leaders, Njoki also is working to create awareness among domestic workers about their rights and advance their efforts to become union leaders. Many are sexually harassed and assaulted, and fearful of speaking out about their treatment, she says.

Women workers and even women leaders “can’t come out because they are afraid, they are threatened. It’s not easy to come out and say ‘this is my right [to not experience gender-based violence on the job]’ as a young person, as a young lady.”

As she takes on the challenges facing young workers, Njoki is optimistic about the future. “So many ladies, even young people and young men, they are ready to listen and they are ready to work together so we can drive the agenda together.”

Aug 15, 2017

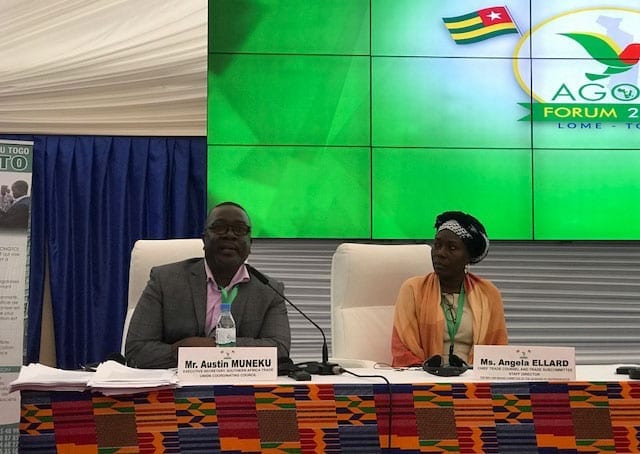

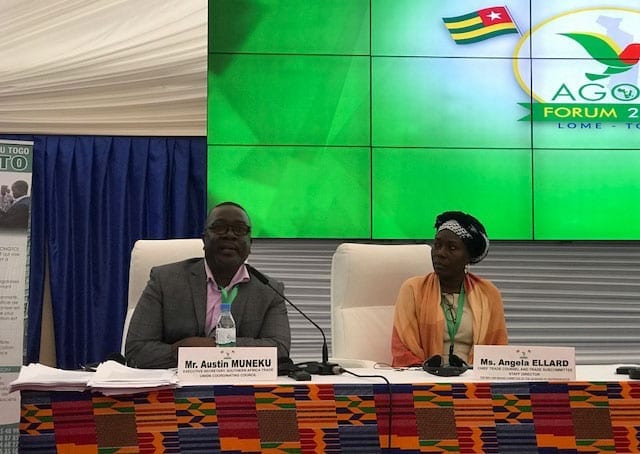

Meeting in Togo for the annual African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) forum this month, nearly 20 leaders from key African trade unions joined forces to advance the creation of good jobs and safe workplaces through fair trade.

The forum “is a venue for workers to have their voices heard by officials and politicians all over the world,” says Eliamane Diouf, secretary-general of the Confederation of Free Trade Unions of Senegal (CSA), who attended the conference.

It offers unions the opportunity to “make sure companies comply with international standards of labor by complying with the rights of workers,” he says.

“Fair trade is where everybody wins” —Georges Koanda, USTB general secretary Credit: Solidarity Center Emily Williams

Also at the August 7–10 conference, Georges Koanda, general secretary of the Workers Trade Union of Burkina Faso (USTB), says unions seek to “make sure that all the businesses and small- and medium-sized enterprises that work with AGOA create decent work.

“To me, fair trade is where everybody wins—the worker wins, the employer wins, the government wins and the public around the world wins,” Koanda says. “But to achieve this, the government has to put up a lot of measures and procedures so as to comply with the norms in their trade with the United States.”

The CSA and USTB were among nine Solidarity Center partners at the event, where union leaders released a statement outlining how AGOA should best achieve fair trade for workers and their communities. The first goal is “strict adherence to international labor standards, respect for human rights, democracy and the rule of law,” as “integral performance benchmarks without exception to all AGOA investments and business practice.”

Signed into law in 2000, AGOA was originally an eight-year trade preferences pact providing sub-Saharan African countries that met certain criteria with access to the U.S. market for goods such as clothing, agricultural products and auto components. It has since been extended to 2025. AGOA’s goals involve encouraging economic growth and development as well as regional and global integration of sub-Saharan Africa.

AGOA Provisions for Worker Rights Hold Countries Accountable

Crucially, the pact includes key worker and human rights protections that countries must meet to enjoy AGOA benefits. In 2014, the United States suspended Swaziland from AGOA for failing to allow worker and civil society groups to freely associate and assemble. The Swazi government’s attacks against workers and their unions have since decreased, says Muzikayise Mhlanga, Deputy Secretary General of the Trade Union Congress of Swaziland (TUCOSWA).

“Even though we are not where we want to be in terms of rights, human rights, political rights … I think in terms of the labor component, we are improving. Through the suspension of AGOA, our labor laws have been amended, the suppression of terrorism act also has been amended, the public order act … also has been amended,” all for the better.

The action shows governments “if you don’t adhere to the benchmarks you’re going to lose AGOA,” says Mhlanga.

Nearly 20 leaders from key Africa trade unions, all Solidarity Center partners, took part in AGOA 2017 in Togo.

In fact, everyone along the supply chain benefits when workers have decent wages and working conditions and the freedom to form unions and associations, says Koanda.

“When we look at the number of Africans in the supply chain, we realize that these workers and their rights are not respected because they can’t make a living in this value chain. In this case, AGOA is very, very important because AGOA has requirements that our countries have to comply with.”

The unions roundly support AGOA, saying in their statement that it “offers an opportunity for African countries to address the decent work deficit, especially for women, youth and migrant workers as well as reduce poverty and inequalities.”

But the key, says Mhlanga, is decent work—employment that provides living wages in workplaces that are safe and healthy, with fairness on the job and social protections for workers when they are sick, injured or retire.

“We should not compromise the conditions of service just for the sake of getting jobs,” he says. “They should be decent jobs.”

Emily Williams, Solidarity Center senior program officer for Africa, conducted interviews for this report.

African trade unions and civil society organizations are leading this discussion and have responded with initiatives such as the launch of a transnational movement,

African trade unions and civil society organizations are leading this discussion and have responded with initiatives such as the launch of a transnational movement,