May 21, 2014

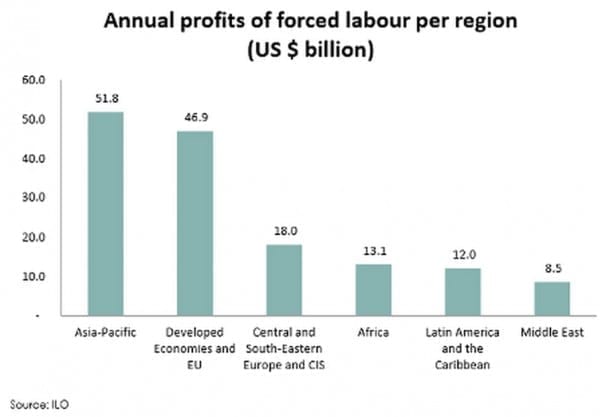

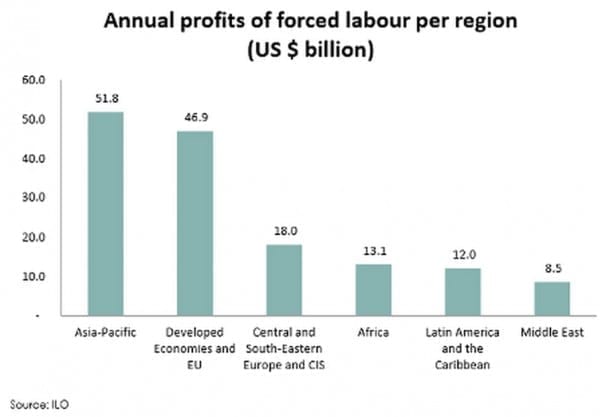

Some 21 million women, men and children are in forced labor, trafficked, held in debt bondage or work in slave-like conditions worldwide, and their toil generates an estimated $150 billion in illegal profits in the private global economy, according to a new report by the International Labor Organization (ILO). The $150 billion in illegal profits is three times more than the previous ILO estimate.

he majority of those in forced labor are women and girls, who make up 55 percent of the total, compared with 9.5 million (45 percent) men and boys. Many of these women are domestic workers. Of the 52.6 million domestic workers worldwide, the report estimates 3.4 million—6.5 percent—are in forced labor. Further, many domestic workers are migrants, often exploited by labor brokers and employers. The report notes that an estimated $8 billion is literally stolen annually from domestic workers in forced labor who, on average, are effectively deprived of 60 percent of their wages.

Overall, $51 billion of the estimated $150 billion in illegal profits results from forced economic exploitation, including domestic work and agriculture, areas where women make up much or most of the workforce. Commercial sexual exploitation accounts for $99 billion.

“Profits and Poverty: The Economics of Forced Labor” finds solid evidence for a correlation between forced labor and poverty. In countries where the ILO measured “income shocks” and food insecurity, such as Niger and Bolivia, a larger percentage of forced laborers than people who worked freely came from households where income had declined. In Nepal, only 9 percent of workers in forced labor had lived in food-secure households, compared with 56 percent of freely employed individuals.

The report finds the profit from forced labor is generated from three broad areas:

• $34 billion in construction, manufacturing, mining and utilities.

• $9 billion in agriculture, including forestry and fishing.

• $8 billion saved by private households by not paying or underpaying domestic workers held in forced labor.

An individual is considered to be working in forced labor, according to the ILO’s survey guidelines, if his or her recruitment was not free and involved some form of penalty at the time of recruitment, and if that individual works and lives under duress, and faces any penalty or cannot leave the employer because of the menace of a penalty.

• Read a summary of the report.

• Read the full report.

• In this video, ILO Director General Guy Ryder urges immediate action to end forced labor.

May 21, 2014

Uruguay, South Africa and Germany are some of the countries with the best worker rights records in 2013, while Cambodia, Guatemala and Nigeria are among the worst, according the 2014 Global Rights Indexreleased this week by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC).

Uruguay, South Africa and Germany are some of the countries with the best worker rights records in 2013, while Cambodia, Guatemala and Nigeria are among the worst, according the 2014 Global Rights Indexreleased this week by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC).

The annual index, which documents violations in 139 countries recorded between April 2013 and March 2014, found that in the past 12 months:

- Murder and disappearance of workers were commonly used practices to intimidate workers in at least nine countries.

- Governments of at least 35 countries have arrested or imprisoned workers as a tactic to resist demands for democratic rights, decent wages, safer working conditions and secure jobs.

- Workers in at least 53 countries have either been dismissed or suspended from their jobs for attempting to negotiate better working conditions. “In the vast majority of these cases,” the report notes, “national legislation offered either no protection or did not provide dissuasive sanctions” to hold abusive employers accountable. Rather, “employers and governments are complicit in silencing workers’ voices against exploitation.”

- Laws and practices in at least 87 countries exclude certain categories of workers from the right to strike. At least 35 countries impose fines or even imprisonment for legitimate and peaceful strikes.

The most frequent violation of worker rights occurred when workers went on strike, followed by violations of the rights of workers who sought to join unions.

The survey notes that because countries such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia exclude migrant workers from labor rights, more than 90 percent of the workforce effectively has no recourse for addressing forced labor practices which exist under archaic sponsorship laws.

“The World Bank’s recent ‘Doing Business’ report naively subscribed to the view that reducing labor standards is something governments should aspire to,” said Sharan Burrow, ITUC general secretary. “This new Rights Index puts governments and employers on notice that unions around the world will stand together in solidarity to ensure basic rights at work.”

The index assigns each country a score ranging from one to 5+, with 5+ indicating no guarantee of worker rights due to a complete breakdown in a country’s rule of law (for example, the Central African Republic and Ukraine), five indicating no guarantee of worker rights (for example, Bangladesh, Colombia, Malaysia) and “one” signaling that collective labor rights are generally guaranteed.

The report also offers a detailed look at six countries, one from each of the rankings: the Central African Republic, Cambodia, Kuwait, Ghana, Switzerland and Uruguay.

The ITUC Global Rights Index ranks the 139 countries against 97 internationally recognized indicators to assess where workers’ rights are best protected in law and practice.

Feb 28, 2014

Government restrictions and repression of citizens’ universal right to freedoms of assembly and association topped the list of violations in the State Department’s 2014 annual “Country Reports on Human Rights Practices.”

The report, released yesterday, also singled out the April collapse of the multistory Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh, which killed more than 1,100 garment workers, as among the worst incidences of human rights violations in 2013.

The congressionally mandated report is not an intellectual exercise, said Secretary of State John Kerry in discussing the findings.

It is “about accountability. It’s about ending impunity. The struggle for rights and dignity couldn’t be more relevant to what we are seeing transpire across the globe.”

Get the overview and the full report.

Read Kerry’s statement.

Sep 10, 2013

Trade unionists from dozens of countries are taking part in the quadrennial AFL-CIO Convention in Los Angeles this week—and the Los Angeles Times has video highlights of two international union leaders.

Zahoor Awan, general secretary of the Pakistan Workers Federation, said he is representing the Pakistani union movement in solidarity with the U.S. labor movement. “We share the same … defense of workers and trade union rights.”

Also in the clip is Myrtle Witbooi, general secretary of the South African domestic workers union SADSAWU. Witbooi is chairwoman of the International Domestic Workers NetWork (IDWN), which received the George Meany-Lane Kirkland Human Rights Award Sunday during the covention’s opening session.

“We want to say that domestic workers want respect, they want to be valued for what they are doing,” Witbooi told the Times. “Domestic workers want the same rights as other workers. We are workers like all other workers, so we demand the same respect as all other workers in the world.”

Check out the video.

Jun 22, 2013

Some 197 million people were jobless worldwide in 2012, and an additional 39 million workers have dropped out of the labor market, unable to find employment, according to a new report by the International Labor Organization (ILO).

The ILO predicts the situation will only get bleaker this year, with 5.1 million more workers likely to be unemployed. Young people are the hardest hit: 74 million young workers worldwide are unemployed, a staggering 40 percentof those unemployed globally.

“Global Employment Trends 2013” notes that although the global economy is expected to recover, growth will not be strong enough to bring down unemployment quickly, and predicts that unemployment worldwide will remain at 6 percent up to 2017, not far from its worst level in 2009. The number of unemployed workers is expected to rise further to some 210.6 million over the next five years.

Read the full report.

Jun 3, 2013

Emerging nations—where, on average, employment is rising, income inequality decreasing and the middle class rapidly expanding—are recovering from the global recession faster than developed countries, according to an International Labor Organization (ILO) report released today.

Based on current trends, the “World of Work Report: 2013” forecasts that employment rates across emerging and developing economies will return to pre-recession levels in 2015, while employment rates in advanced economies will only return to pre-crisis status after 2017.

Yet the report also finds that more than 30 million jobs are needed to return employment to the pre-recession level and predicts that nearly 208 million women and men will be unemployed in 2015, rising to 214 million people by 2018. Today, slightly more than the 200 million people are jobless. “Almost everywhere, young people and women find it difficult to obtain jobs that match their skills and aspirations,” according to the report, which is subtitled, “Repairing the Economic and Social Fabric.”

“We need a global recovery focused on jobs and productive investment, combined with better social protection for the poorest and most vulnerable groups. And we need to pay serious attention to closing the inequality gap that is widening in so many parts of the world,” said ILO Director-General Guy Ryder.

Behind the overall national averages, the report paints a less optimistic picture for millions of workers in emerging and developing nations.

• Employment rates in 2012 surpassed pre-crisis rates in 13 of 28 countries with available information. Of the 28, only four developing economies (Jamaica, Jordan, Morocco and Sri Lanka) showed a continuous decline in employment rates at the start of the crisis. In the 11 remaining countries, the employment rates have showed some recovery, but the increase was not sufficient to surpass pre-crisis levels.

• Although the size of the middle-income group has increased, there are three times as many workers on the brink of poverty, whose numbers rose from 1.1 million in 1999 to 1.9 million in 2010, mostly in low- and low middle-income economies.

• Even though global investment by emerging economies increased, accounting for nearly 47 percent of global investment in 2012 compared with only 27 percent in 2000, investment in this group has been stagnant when India and Indonesia are excluded.

Global investment is essential to improving employment, according to the report. Further, it finds that higher minimum wage levels and/or improved compliance in following minimum-wage laws have tended to boost the relative position of low-paid workers. Minimum wages have been accompanied by reductions in inequality at the bottom end of economic distribution, especially in India, Mali, the Philippines, South Africa, Turkey and Vietnam, the report finds. In Brazil and Peru, improved minimum wages appear to have resulted in an expansion of the middle part of the wage distribution.

The report highlights case studies of successful economic initiatives, including those launched by the Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), a Solidarity Center partner. The group has addressed the welfare of women working in India’s informal sector by establishing programs to foster health care, income security and empowerment. The organization provides members with health education and preventative health care, such child immunization.