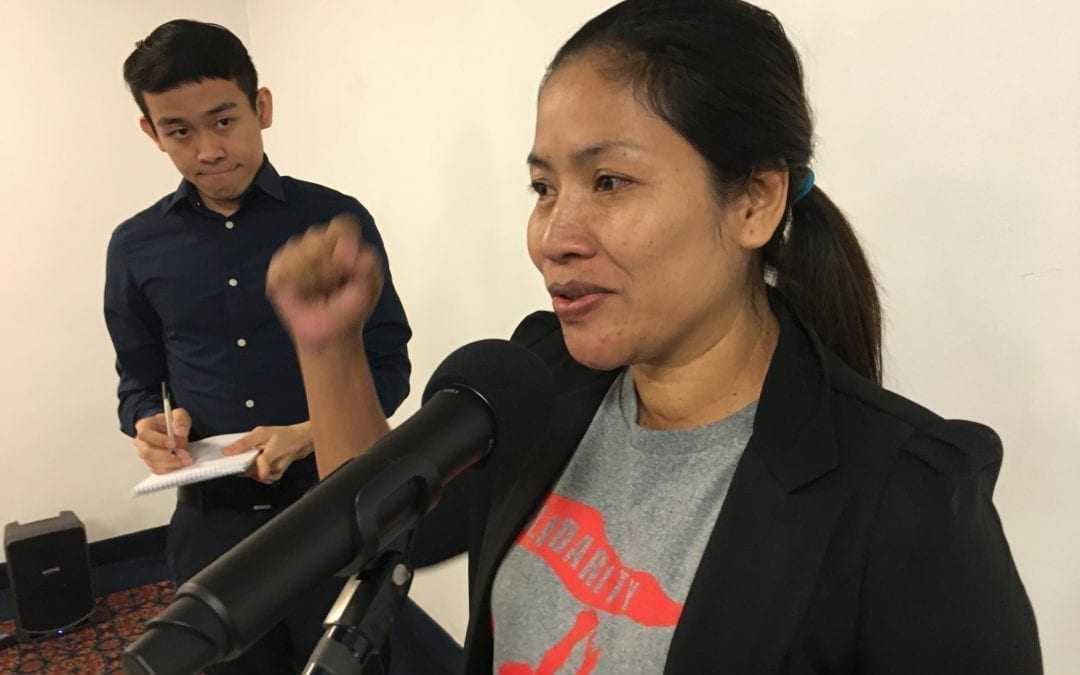

Sophorn Yang Defies Threats to Aid Cambodian Garment Workers

Sophorn Yang, president of the Cambodian Alliance of Trade Unions (CATU), helps lead national campaigns to win a fair wage and to protect workers’ fundamental rights in the face of restrictive Cambodian trade union laws.

Despite receiving threats because of her activism, she remains committed to her mission of bringing more women workers into union leadership, and to the leading the Cambodian worker movement to achieve a nationwide living wage.

“My name is Yang Sophorn, and I am president of Cambodian Alliance of Trade Unions (CATU). I would like to tell people about the living condition of workers in Cambodia. We have seen that their living situation is very difficult. Garment workers work long hours, from Monday to Saturday and Sunday, and they work between 10 and 12 and 14 hours per day.

“Their wage does not correspond to the needs of their living expenses, which means, they only get $150 a month when they work for eight hours per day. So, generally they try to ask for overtime, etc. Therefore (to sum up), these are the difficulties and hardships of garment) workers in Cambodia.”

(Read more about Yang here.)

Gender Equality Goal of South Africa Mine Worker

Ronju: Helping Garment Workers Form Unions despite Danger

Mohammad Ronju, a long-time organizer with the Bangladesh Independent Garment Workers Union Federation (BIGUF) that has helped thousands of workers in 36 factories form unions, was one of the more than 35 people arrested in the December crackdown. On December 27, police entered the BIGUF office in Gazipur, arrested Ronju and later charged him in a January 2015 political opposition explosive substances case, in which he had no involvement. The case carries a sentence of three to twenty years in prison.

After being denied bail repeatedly, Ronju was eventually granted bail and was released on February 16, 2017, after spending over 50 days in jail. The case is still pending.

……………………………………….

I grew up in Dinajpur (northern Bangladesh) and then moved to Dhaka to live with my aunt when I was 8 years old. As I got a little older, I knew I needed to do something to earn money so I got a job in a garment factory.

“At the age of 12 or 13 years old, I started working in a factory in Dhaka as a helper in the finishing section making 600 taka a month ($7.40).

“In 2006, I began working in a different factory in Gazipur where some of my co-workers first introduced me to BIGUF when there was a problem with unpaid wages. About 25 of us went to the federation office, and they worked with us to resolve the problem.

“Sometime later in 2011, when I worked in another factory, I tried to organize a union but I was fired. Another worker and I led the effort to sign up workers for the union and submitted an application for registration to the government. I was terminated for union activity but BIGUF fought to get me reinstated in the factory. However, management later brought armed men into the factory to force me to leave my job and move from the area for good. They also went to my home and threatened my family.

“I left that factory and became a union organizer with BIGUF. I’m doing this because I was an abused worker and I want to do something for other workers. A union is the road to worker rights.”

With Union, Rana Plaza Disaster Would Not Have Happened

“Since Rana Plaza, workers are now able to formally have their unions registered (by the government; a legal requirement) where they were not able to before. Workers are now more familiar about what trade unions are and what they do. Workers are also more aware of their safety. If there was a union at Rana Plaza, (the collapse) may not have happened. Union leaders could have talked with the owners about the problems there, and maybe so many workers would not have lost their lives. Maybe the leaders would have been harassed by the management, but so many workers would not have died.”

No Food, No Bed in Prison

“On December 27, I was at our BIGUF office in Gazipur when several police entered. They began reading a list of names of people that they were looking for and read my name. They arrested me and took me away in their car. I asked them what was my (reason for being arrested). They told me that there was no case against me but that they had received instructions to arrest me, so that is what they did.

“They brought me to a police station. I didn’t want to get in touch with my family because I didn’t want to worry them. Two days passed and I didn’t know what was going on. In lock-up we weren’t allowed anything—no shoes, no bed. I slept on the floor. The police didn’t feed me but some of the other prisoners shared their food. Eventually, they transferred me to the main jail where one of the officers at the gate used bad language with me.

“I was in jail for one month and 19 days. The first week in jail was really tense. I knew BIGUF would help me but I have a family and wasn’t sure how they would handle the situation. I also had communication with lots of factory workers and wasn’t sure what would happen to them. But after I was able to establish communication with everyone outside, I felt lighter.”

‘Police Instructed by Higher Authorities to Arrest Us’

“Asad and Arif (two other BIGUF organizers arrested in Gazipur several days before Ronju) were also with me in jail. Asad and I slept in the same place, and Arif slept in a different place. Every morning we had to wake up at 5 a.m. and kneel on the ground so that the guards could count the prisoners. This would happen several times a day. The authorities would provide little and very low-quality food. No one could eat the vegetables and the small amount of rice provided was full of insects. But BIGUF arranged other, better quality food and items like blankets and plates to help us inside the jail.

“The false charges against me are about a political opposition case [and explosives?]. They put me in this case just to harass us (BIGUF). There is nothing there. The police were instructed by higher authorities to arrest us. BIGUF really works for the workers and that is why we were targeted.

“I have a wife and an 11-year-old son. I have received some pressure from my family, but I cannot leave my organization. This work is in my blood. We have not made any mistakes but we are harassed. We hope for the case to be withdrawn so we can again work more openly with the workers again.

“Although I’m on bail, because I have a case pending against me I still have to appear in court one day a month. The case is such that I cannot miss a hearing or I will be arrested and put in jail again.”

Rosalie, Domestic Worker from DRC, Champions Migrant Worker Rights in Morocco

Hi, I am Rosalie Ewengue, I am Congolese. I have worked as a domestic worker in Morocco for eight years, and have been an undocumented migrant worker for six years. I participated in an awareness-raising campaign with the Afrique Culture Maroc and Solidarity Center that focused on the issues facing undocumented migrant workers, and I tried to encourage undocumented women migrant workers to approach the regularization office and register themselves. That’s how I became an activist and a member of Collectif des Travailleurs Migrants au Maroc (Morocco Migrant Workers Organization).

In 2015, and always with Solidarity Center’s partnership, we launched an awareness-raising campaign focused on domestic workers. The goal was to identify the domestic workers and to learn more about their status and working conditions.