Oct 13, 2021

Around the world, young people with few job options are forced to take whatever work they can find, no matter how low the pay or insecure the work. Many sign on with platform-based jobs to get by. Others leave their country with the hope of finding decent, secure work elsewhere, looking for a chance to fairly compete on a level playing field.

The latest Solidarity Center Podcast takes a look at what’s happening in Serbia, where one in four young people are not employed and not in school, and how unions there are meeting the challenges.

“The number one issue for all countries in the region and all young people is decent employment and the potential to find a job for each person in a way that is transparent and efficient and without corruption,” says Bojana Bijelovic Bosanac, a political scientist and expert adviser in the International Department at Confederation of Autonomous Trade Unions of Serbia (CATUS).

Bosanac tells Solidarity Center Executive Director and podcast host Shawna Bader-Blau about a union-lead survey among young workers in the Balkan region during the pandemic in which many reported being unpaid for their platform work as programmers, customer service reps, telecenter workers and delivery drivers, with nowhere to turn for support. Making the union their home is a key goal for CATUS and unions across Serbia.

“When we talk to young people, we want them to know that they are part of the union. They are the future of the union. We are inviting them always to approach, to come, to participate and to be leaders of the union.”

The Solidarity Podcast Available Wherever You Get Podcasts

Listen to this and all Solidarity Center episodes here or at iTunes, Spotify, Amazon, Stitcher, Castbox or wherever you subscribe to your podcasts.

The Solidarity Center Podcast, “Billions of Us, One Just Future,” highlights conversations with workers (and other smart people) worldwide shaping the workplace for the better.

Check out recent episodes of The Solidarity Center Podcast.

This podcast was made possible by the Ford Foundation and the generous support of the American people through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement No.AID-OAA-L-16-00001 and the opinions expressed herein are those of the participant(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID/USG.

Oct 6, 2021

Worldwide, 2 billion workers perform essential work selling goods in street markets, driving taxis or cleaning homes. The vast majority of these jobs are low wage, with no security and no paid sick leave or health care.

In Nigeria, where more than 80 percent of the population works in informal economy jobs, these workers are joining together to fight for their right to decent work through the Federation of Informal Workers’ Organizations of Nigeria (FIWON), a nationwide association with hundreds of branches across the country.

On the first Solidarity Center Podcast this season, Solidarity Center Executive Director and podcast host Shawna Bader-Blau talks with Gbenga, FIWON founder and general secretary. Gbenga describes how informal economy workers are using their collective power, building coalitions with allied organizations and making key gains, like ending evictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, addressing unfair, burdensome taxation on vendors and, importantly, winning recognition by government and society that they must have the same rights and respect as all workers.

“Poor working people must have access to basic social security, but it doesn’t start with that,” says Gbenga, who goes by one name. “It starts with even the right to work without fear. The right to work without harassment and unnecessary molestation. The right to access public spaces as commonwealth, as something that belongs to all of us.”

Tune In to The Solidarity Center Podcast!

Listen to this and all Solidarity Center episodes here or at iTunes, Spotify, Amazon, Stitcher, Castbox or wherever you subscribe to your podcasts.

The Solidarity Center Podcast, “Billions of Us, One Just Future,” highlights conversations with workers (and other smart people) worldwide shaping the workplace for the better.

Check out recent episodes of The Solidarity Center Podcast.

This podcast was made possible by the Ford Foundation and the generous support of the American people through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement No.AID-OAA-L-16-00001 and the opinions expressed herein are those of the participant(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID/USG.

Oct 4, 2021

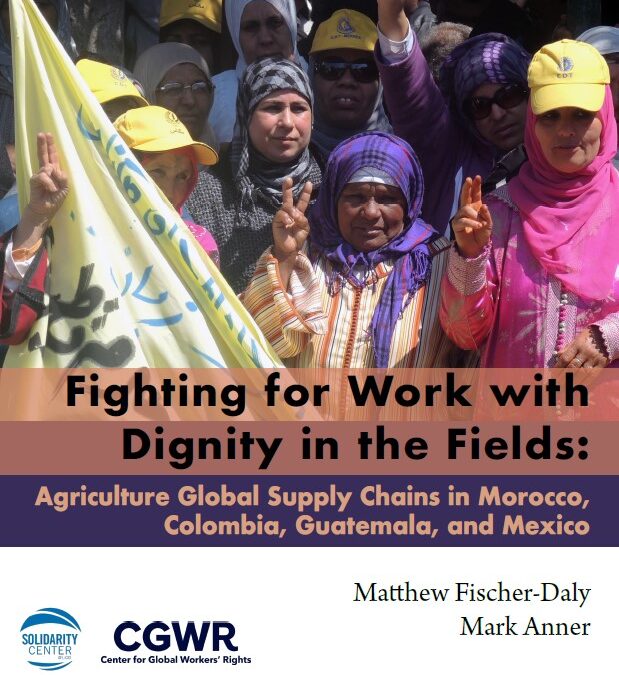

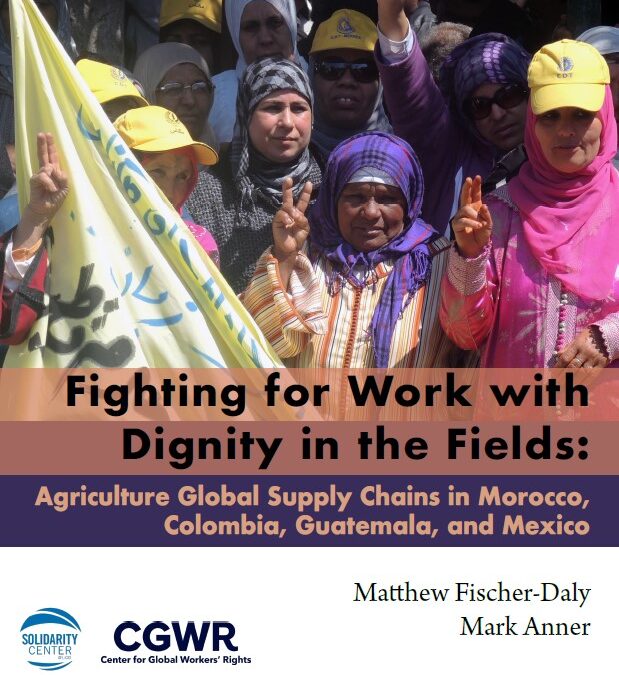

Where unions establish collective bargaining, they initiate the strongest mechanism for protecting agricultural workers’ rights, health and dignity according to a new report prepared for the Solidarity Center by researchers at Penn State’s Center for Global Workers’ Rights (CGWR).

“Fighting for Work with Dignity in the Fields: Agriculture Global Supply Chains in Morocco, Colombia, Guatemala, and Mexico,” seeks to understand employment relations in agricultural global supply chains and the struggle for dignity and empowerment of workers who are providing the world’s food. The report analyzes five agribusiness sectors including palm oil in Colombia, bananas in Guatemala, strawberries in Mexico, and grapes, olives and wine in Morocco.

In all four countries and five sectors, workers’ collective action has been “almost entirely responsible for increasing respect for workers’ rights” in a context where: 1) governments are constraining worker rights in favor of maximum employer flexibility in support of national, export-oriented development policies and, 2) global retailers are putting downward pressure on wages by curtailing the amount of capital that production workers might negotiate over with their employer for wage increases.

Researchers found that—where established—unions are performing the task of government to protect workers’ legal rights, increasing stability in otherwise precarious employment sectors and providing a mechanism for women to advance gender equality in job status and earnings as well as address rampant gender-based violence associated with their jobs—including transportation to and from the workplace. For example:

- In Colombia, unions negotiated agreements that increased direct hiring by three palm oil production companies, pushing back against the sector’s rampant use of labor subcontracting, which denies subcontracted workers union representation and provides them lower pay and more precarious work.

- In Guatemala, union representation in the banana sector means employer compliance with laws on working hours, remuneration, provision of personal protective equipment, voluntary overtime, protection from sexual abuse and freedom of association.

- In Mexico, while not achieving collective bargaining, the 2015 strike during strawberry harvest compelled employers to increase wages and registration workers in the national social security system, e.g., toward compliance with laws requiring living wages and consistent registration.

- In Morocco, the country’s labor law is enforced in grape, wine and olive oil production due to the agreement secured for workers by the Confédération Démocratique du Travail (CDT).

Addressing inequality and gender-based violence and harassment

Women, who comprise between 50 percent and 70 percent of the informal workforce in commercial agriculture, are especially vulnerable to sexual harassment, physical abuse and other forms of gender-based violence at work. Unions are addressing the gender-based violence that is common in all five sectors studied, as well as gendered pay discrimination and division of jobs that reduces women workers’ earnings, as follows:

- In Guatemala’s banana sector, women workers covered by union contracts report 50 percent less incidence of sexual harassment than peers at nonunion plantations because union women “can inform the company,” a female unionist explained.

- Women in Mexico’s strawberry sector reported that the 2015 strike helped reduce sexual abuse at work.

- While Moroccan law does not prescribe comprehensive equitable treatment, women’s participation in CDT negotiations with Zniber-Diana resulted in clauses requiring equity.

Although union density remains extremely low in all sectors studied, the report concludes that, “[w]here workers are able to unionize and collectively bargain, conditions improve, wages increase and gender-based violence is curtailed,” and that increased union density and collective bargaining coverage will expand these improvements.

Oct 4, 2021

Millions of street vendors worldwide lost their livelihoods nearly overnight during the pandemic, unable to sell in open markets during lockdowns or unwilling to risk their health to do so.

Maria do Carmo, founder of United Camelôs Movement street vendor association in Sao Paulo, spoke at the Essential Worker Summit.

But street vendors in Brazil, through the National Union of Street Vendors Workers (UNICAB), achieved basic emergency income to ensure they could survive. UNICAB went on to collect sufficient signatures from members of the Brazil National Congress to create a Parliamentary Front to defend informal traders’ rights, marking the first time they will be represented at the national level.

“We had many successes this year during the pandemic,” says Maria do Carmo, a street vendor and leader of the United Camelôs Movement (MUCA) in Rio de Janeiro. MUCA, organized by do Carmo in 2003, has further built its collective strength by joining UNICAB, a countrywide association formed in 2014.

Do Carmo says she is most proud of MUCA’s victory in convincing city officials to not charge customary fees during the pandemic because vendors sold so little. “We did it with a lot of protest—going to the town hall and participating in public debate.

“A good success is a collective one.”

Building Success Through Collective Action

Marli Almeida is among many street vendors in Brazil seeking basic rights on the job. Credit: UNICAB

In September, informal economy workers joined in a first-of-its-kind worldwide gathering to outline a vision for a just economic recovery that ensures protections for workers and advances worker rights. Over three days, the Essential For Recovery summit brought together well-known actors, global union leaders and policymakers who talked with street vendors, domestic workers, farm workers and others who shared their experiences and demanded a response that urgently and effectively protects the most marginalized.

Many Essential For Recovery participants pointed to workers joining together in unions and associations as one of the most effective means for achieving rights. In Rio, do Carmo and other street vendors further showed the power of collective action during the pandemic when they successfully lobbied the municipal government to stop police from confiscating vendors’ merchandise as means of harassment.

“After MUCA joined UNICAB, we saw we had more presence, we are more respected in the state [of Rio] because of strength of UNICAB,” she says. Through the organization, street vendors connect with each other across the country, learn about available resources and join together to advocate for their rights at the local and national levels. (Check out UNICAB’s podcast with street vendors, in Portuguese).

Street Vendors Part of Growing Informal Economy

Edivaldo, a member of the Sintraci Informal traders trade union of Recife Pernambuco, protests violence against street vendors. Credit: UNICAB

Street vendors are part of the global economy’s vast and growing informal workforce—61 percent of all workers are in the informal economy, where they rarely have paid sick leave, safe jobs or access to affordable health care. Street violence—especially from police and other local officials—is the biggest problem they face in Brazil and worldwide, says Maira Villas-Bôas Vannuchi, organizer of StreetNet International for the Americas. Street vendors, the majority of whom are women in many countries, are especially vulnerable, exposed to extreme heat or cold, often with no access to toilets or clean water.

“Many women, single mothers, had to go work in the streets because that was the option they had,” says do Carmo.

Two weeks after giving birth, Maria do Carmo returned to the streets of downtown Rio, where she sells women’s clothes. The police, who street vendors there say regularly abuse them verbally and physically, assaulted do Carmo.

“They beat me up pretty hard,” she says. “I was injured and had to take leave from work.”

It took do Carmo a month before she was healed sufficiently to return to her job, but when she did, she was determined to fight for the rights of street vendors to make a living. Do Carmo went on to organize street vendors across the city in MUCA.

“Street vendors are workers without rights,” says Vannuchi. “They work every day, they contribute to the economy of the country, but they are not recognized as workers.”

Respect, Recognition

Connecting with and organizing street vendors who work on different days and at varied hours spread across cities and along roads was challenging—and involved many arrests as local officials sought to disrupt their efforts to gain political and social rights, with police targeting leaders like do Carmo. MUCA and UNICAB are now part of StreetNet International, a global alliance of street vendors launched in South Africa in 2002.

Do Carmo ran for office in Rio and although she did not win the election, she says the visibility of her campaign and the efforts of other vendors to win office brings their issues to the attention of the public and lawmakers. “Today we have respect from City Hall,” she says.

A single mother, do Carmo has supported four children with her work and plans to remain a street vendor, despite her organizational involvement and efforts to seek elective office. She emphasizes that street vending is a job many want and need to do—but in decent conditions and with respect.

“A good future will be a future when street vendors—all of them—have confidence in the value of their work, when society considers what we do is work and when our work is appreciated by society, and we are not marginalized as we are now.”

Sep 15, 2021

When hundreds of thousands of Colombians took to the streets for weeks last spring to protest the government’s move to give wealthy corporations and rich individuals huge tax breaks while raising taxes on working people, workers and their unions were at the forefront.

Despite the state’s brutal response, in which violence—including illegal detention, torture and the use of lethal weapons—was directed against workers, women and Black and Indigenous communities, the National Strike Committee, a broad coalition of rural workers, the LGBTQ community, environmentalists, women’s organizations and young people, won big victories, says Francisco Maltés.

Maltés, president of the Unitary Workers Center (CUT), the largest union confederation in Colombia, speaks with Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau in a special episode of The Solidarity Center Podcast.

“We were able to do away with the worst tax reform proposal that had ever been seen in Colombia,” says Maltés, describing one of the movement’s gains. Just as important, he says, is that for “the first time in the history of social struggles in Colombia,” unions and their allies can define an agenda and help shape public conversation.

“We are now able to talk about basic income, free tuition, wage subsidies for small and medium businesses. Issues that matter to workers and the average people in Colombia.”

Listen to this and all Solidarity Center episodes here or at iTunes, Spotify, Amazon, Stitcher, Castbox or wherever you subscribe to your podcasts.

Stay Tuned for Season Two!

The Solidarity Center Podcast, “Billions of Us, One Just Future,” highlights conversations with workers (and other smart people) worldwide shaping the workplace for the better.

We will back in a few weeks with Season Two, so be sure to join us for a new episode each Wednesday!

Meantime, listen to our special summer episode with union leader Phyo Sandar Soe who speaks from a safe house in military-controlled Myanmar to share how workers have risked their lives on the frontlines for democracy since the February 1 coup.

Also: Check out the full first season of The Solidarity Center Podcast.

This podcast was made possible by the Ford Foundation and the generous support of the American people through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement No.AID-OAA-L-16-00001 and the opinions expressed herein are those of the participant(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID/USG.

Sep 14, 2021

Workers who risked their health to provide essential services during the pandemic joined with actors, global union leaders and policymakers in a first-of-its-kind worldwide gathering to share their experiences and demand a response that urgently and effectively protects all people, and especially the most marginalized.

Yalitza Aparicio spoke in support of government action to ensure essential workers have decent wages and safe work.

“COVID-19 has taught us about the importance of workers in all sectors and recognize that they deserve dignified work and they are important in the world economy,” said actor Yalitza Aparicio. “Governments know about this. But, what are they doing about it?” Aparicio was among dozens of speakers during the September 8–10 Essential For Recovery virtual summit who pointed to the need for action to ensure decent wages, rights and social protections like paid sick leave so workers deemed “essential” during the pandemic will not be left behind after the crisis passes.

As the Summit made clear, essential workers often work in the informal economy. “They have no rights, no minimum wages, no rule of law, no social protection,” said Sharan Burrow, general secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC). “We have to get a minimum living wage to all essential workers. We have to afford them collective bargaining rights. And we have to put in place universal social protection in safe workplaces.”

Organized by the Open Society Foundations and hosted by actor Sophia Bush, Essential For Recovery focused on four themes: increased income and improved working conditions; healthy and safe workplaces and access to health care; social protection benefits and support for vulnerable workers; and ending gender-based violence and harassment at work.

The Solidarity Center co-sponsored the event, along with HomeNet International, ITUC, StreetNet International Alliance of Street Vendors, UNI Global union and WIEGO.

Catch the full three one-hour sessions:

Unions, Collective Action Key to Building Back Better

Mithqal Zinati (right), a coordinator for Jordan’s agricultural sector, says workers need the right to form unions to ensure safe workplaces.

In Jordan, where workers have limited rights to form unions, Mithqal Zinati, a coordinator for the country’s agricultural sector, says the government’s action “keeps thousands and tens of thousands of workers from being part of providing solutions to the problems facing the agriculture sector. This eliminates the role of workers to defend their rights and protect their interests and to see beneficial gains.

“For everyone, having a union is very beneficial. For farmers and for workers at the same time.”

As the pandemic highlighted, workers with unions often more readily had access to personal protective equipment (PPE) and decent wages. Summit participants discussed the power of grassroots organizing to improve workers’ lives, and described how, over the last year, essential workers in the formal and informal economies went on strike to win access to PPE and vaccines. They took to the streets and to social media to demand more democratic societies and governments.

Maria do Carmo, a Brazilian street vendor, organized street vendors into a nationwide organization, the National Union of Hawkers, Street and Market Vendor Workers of Brazil (UNICAB), and through their collective power, raised awareness of their issues with politicians. “Today we have respect from City Hall,” she said.

“Over the past two days, we’ve seen proof of the effectiveness of collective action, and of the importance of eliminating gender inequities. But at the heart of it all is power,” said Bush, at the start of the third and final session.

Women Targets of Gender-Based Violence, Burdened with Carework

The pandemic also forced many to work from home where women disproportionately engaged in care work. Globally, women lost $800 billion in income due to COVID-19.

Mercedes D’Alessandro, the first national director of Economy, Equality and Gender in Argentina, described a study in which she found that during the pandemic, three-quarters of women did unpaid care work, amounting to 22 percent of GDP—up from 16 percent of GDP before COVID-19.

“The truth is that the increase in time that women dedicate to care activities means also a smaller opportunity to go out and look for a job, continue with their jobs, develop their careers or study, graduate from university,” she said.

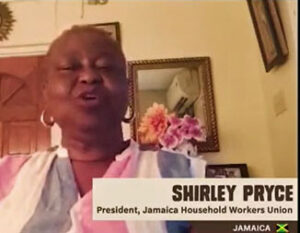

Shirley Pryce, president of the Jamaica Household Workers Union, urges governments to ratify a treaty ending gender-based violence at work.

Women also experienced high levels of violence during lockdowns, further highlighting the need for governments to ratify an International Labor Organization (ILO) treaty (Convention 190) to end gender-based violence at work.

“Violence and harassment can happen anywhere, and it can happen to anyone,” said Shirley Pryce, president of the Jamaica Household Workers Union. “But this must not be tolerated. It must stop. Let us push together for governments to ratify this very important convention.”

C190 covers wherever work is performed, such as where workers take a rest break or meal or use sanitary, washing or changing facilities, and includes commuting to and from work.

“We are seeing a new normal. Home has become a workplace,” said Rose Omamo, general secretary of the Amalgamated Union of Kenya Metal Workers, a Solidarity Center partner. Employers must ensure workers have what they need to work from home, including safe workplaces, she said.

Building to a Better, More Equitable Tomorrow

Artists like Sinkane performed during the Essential Worker Summit.

Omamo was in conversation with Rosa Pavanelli, general secretary of Public Services International. The summit provided opportunities for shared discussion, “lightening rounds” featuring workers telling their stories and urging action, and videos showcasing worker issues such as the Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT)’s documentary on women agricultural workers seeking safer transportation.

Essential for Recovery also featured multimedia presentations by performance artists such as Khansa, a singer, songwriter and dancer from Lebanon; U.S. actor Martin Sheen; Sonam Kalra of the Sufi Gospel Project; and Ahmed Abdullahi Gallab Sinkane, a Sudanese-American musician.

“I stand with all essential workers around the globe. The domestic and agricultural workers, waste pickers, street vendors, caregivers and home-based workers who make our world run,” said Sinkane, before performing U’Huh.

“During the pandemic, we saw how essential they really are. They deserve a living wage, proper employment conditions and a safe and healthy workplace,” he said. “Let’s build forward to a better, more equitable tomorrow.”

Key participants in Essential For Recovery also included Christy Hoffman, UNI Global Union general secretary; Maina Kiai, former United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; Guy Ryder, ILO director general and Ai-jen Poo, National Domestic Workers Alliance executive director.