Sep 2, 2022

A new Labor Center in Mexico will advise workers about their rights and how to mobilize and organize unions and collectively bargain. The Labor Center, at the Autonomous University of Querétaro in central Mexico, is supported by the Solidarity Center and the UCLA Labor Center.

“The aim is to strengthen and promote the full recognition of labor rights, freedom of association and organization, and the democratic participation of workers through research, linkage and accompaniment,” said Labor Center Director Dr. Javier Salinas García. Salinas spoke at a recent Solidarity Center event in Mexico to announce the opening.

The Labor Center comes three years after Mexico’s government announced a series of comprehensive labor reforms to establish a democratic unionization process, address corruption in the labor adjudication system and eradicate employer protection (“charro”) unions prevalent in the country.

The Labor Center is “a way to respond to the needs of the situation,” said Beatriz García, Solidarity Center Mexico deputy program director.

“I think we all agree that Mexico is going through a historic moment. The labor reform responds to the demands that have been the objectives of the struggle of many workers for years, for decades, and reflects some positive practices of the independent unions,” she said.

The event featured a panel of independent union members and leaders who discussed the future of the labor movement in Mexico in the wake of historic labor law reforms.

Panelists explored the role that democratic and independent trade unions in promoting labor reform implementation in Mexico three years after the 2019 Labor Reform and negotiations of the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (UMSCA/T-MEC).

Speakers shared how they are using the tools of labor reform to organize on their worksites.

“We are the delegates, and we call our colleagues to share information about the Union League,” said Sonia Cristina García Bernal. “We have helped colleagues who were told they were going to be fired without severance pay. We have been able to get them severance pay. We have been able to get them rehired.”

“After these three years, the tool that we use the most is fast response mechanisms,” said Imelda Guadalupe Jiménez Méndez. “This has been a very important tool.”

In addition to Beatriz García, speakers included: Imelda Guadalupe Jiménez Méndez, Secretary for Political Affairs, the Miners Union (Los Mineros); Julieta Mónica Morales, General Secretary, Mexican Workers’ Union League (Liga Obrera Mexicana); Rita Guadalupe Lozano Tristán, Mexican Workers’ Union League (Liga Obrera Mexicana); Alejandra Morales, General Secretary, Independent Union of National Workers in the Automotive Industry; and Sonia Cristina García Bernal, Special Delegate, Mexican Workers’ Union League (Liga Obrera Mexicana).

Aug 23, 2022

Workers demanding relief from inflationary pressure on wages will launch a general strike on Thursday unless the Kosovo government grants public sector workers an emergency wage increase of almost $100 per month. This proposed amount will provide most public sector workers—including doctors and nurses—with an immediate 20 percent increase in lieu of a long-delayed wage law, says the Union of Independent Trade Unions of Kosovo (BSPK).

“It is the [failure of] the wage law that obliges us to go on strike,” says BSPK Chairperson Atdhe Hykolli, who announced that the work stoppage will last until the workers’ plea for relief is met.

According to BSPK, Kosovo’s workers and their families can no longer meet their basic needs due to historic inflation. The country’s inflation rate is inching higher each month, reaching a 14-year high of more than 14 percent in June and it increased again in July.

Escalating costs for food and non-alcoholic beverages, housing and utilities, and transportation are the main driver of inflationary pressure on wages in Kosovo. For the 12 months ending in June this year, the cost of transportation increased more than 30 percent while the cost of food and non-alcoholic beverages increased by more than 17 percent. From 2003 through 2021, the country’s inflation rate was less than two percent per year. The average public sector worker’s take-home pay of $542 has not increased since 2021.

“The situation for workers in Kosovo is like those in many countries around the world: Rising costs coupled with stagnant wages is simply not sustainable,” says Solidarity Center Southeastern Europe Country Program Director Steven McCloud.

Aug 23, 2022

In a significant assault on worker rights in Ukraine, President Volodymyr Zelensky last week signed into law legislation that deprives around 73 percent of workers of their right to union protection and collective bargaining.

“For more than 15 months, the Federation of Trade Unions of Ukraine, in solidarity with other trade unions, with support of the international community, actively opposed promotion of the anti-labor draft law,” the Federation (FPU) said in a statement.

The Confederation of Free Trade Unions of Ukraine (KVPU) stated, “KVPU will not tolerate a blatant violation of the rights of workers, their constitutional guarantees and international norms and standards. We will continue the fight for workers’ rights.”

The law references “freedom of contract,” which the non-governmental organization Labor Initiatives says “provides ample room for employers to prescribe literally any provisions in a contract, while workers, desperate for jobs during a pandemic, will likely accept such provisions.” Labor Initiatives is a Solidarity Center partner that works closely with unions and other NGOs, analyzes labor laws and advocates for worker rights at the individual and national levels.

The law applies to Ukrainian companies with fewer than 250 workers, and is valid during martial law in Ukraine, but labor experts express concern that it may be extended.

The law, which amended the Labor Code of Ukraine, is the latest in a string of legislation targeting worker rights and the ability of unions to function freely. For the past two years, lobbyists have pushed laws in Parliament that reduce wages, limit the use of formal contracts that ensure workers have job stability and weaken their collective voice by targeting unions. Under the restrictions of martial law and the chaos of war, members of Parliament have passed many of these measures.

“Instead of having some greater protection of labor rights, greater protection of the people who are baking bread, washing dishes or cleaning the streets, since March we faced very regressive labor reform in Ukraine,” George Sandul, a Kyiv-based labor lawyer, said on the latest episode of The Solidarity Center Podcast, where he detailed the laws.

Global Opposition to Attacks on Worker Rights

The global labor and human rights communities have widely rallied in support of workers and their unions in Ukraine, many taking part in an online campaign to oppose the legislation.

The FPU points out that in 2021, the European Parliament indicated as part of the European Union–Ukraine Association Agreement that Ukraine’s “measures to improve the business climate, attract direct investment and promote economic development cannot be implemented at the expense of limiting workers’ rights and worsening working conditions.”

With martial law prohibiting workers from public protest and strikes, the FPU, KVPU and other Ukrainian trade unions say they will challenge the law in Ukraine’s Constitutional Court, the International Labor Organization and other international and European bodies.

“We will also vigorously oppose dozens of other anti-labor and anti-union pieces of legislation that government lobbyists are trying to push through the Parliament,” the FPU says.

Aug 9, 2022

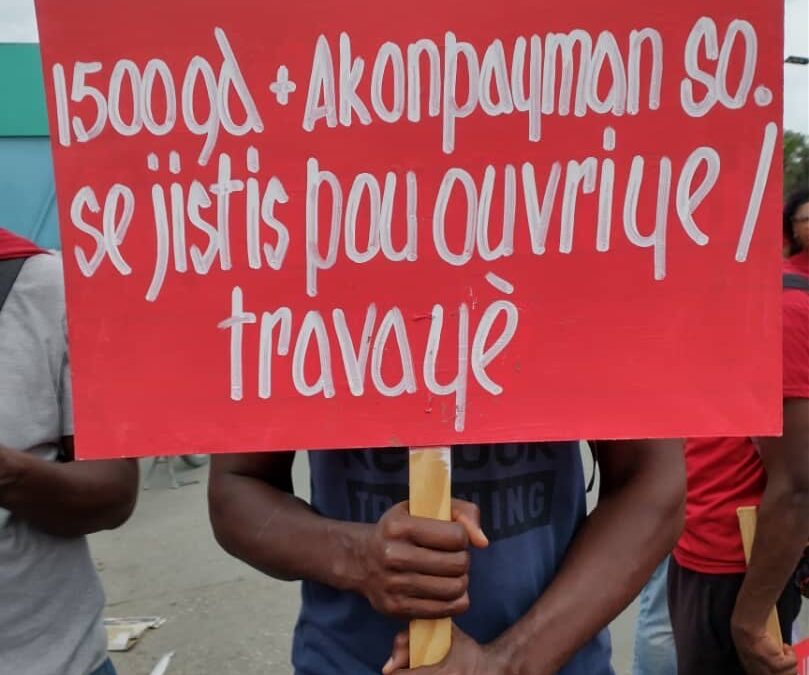

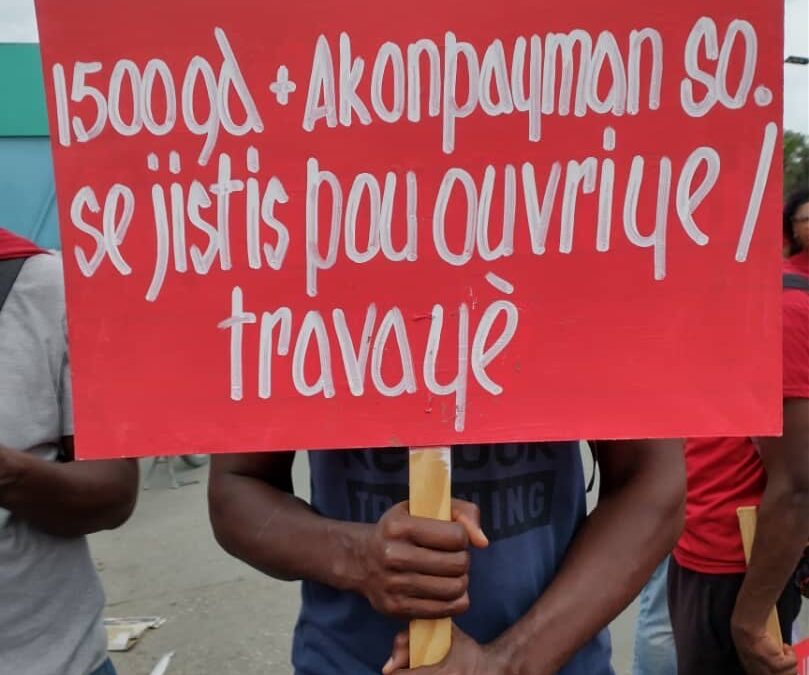

Haitian garment workers scored a huge victory as a coalition of unions negotiated an agreement with the government to provide garment workers in Port-Au-Prince with transportation and food stipends.

“In our struggle for a better working environment and fair wages we have always emphasized that the government should provide social support to workers, especially those in the textile sector. And here it is for the first time that our demands have been heard, even if it is not yet in effect, but the government has planned to accompany the workers by offering them transportation and food costs for an amount of 135,000,000 gourdes ($1,116,595),” said Telemarque Pierre, coordinator of SOTA- Batay Ouvriye.

“From now on, we would like the government to take care to include these accompaniments in the annual budgets so that the workers can always benefit from these advantages.”

The government will distribute the funds via a mobile app. The stipend will cover the cost of travel to and from the factory, and include a lunch stipend. Inflation and gang violence have led to skyrocketing prices for food and fuel such that workers cannot afford travel to and from work or food at lunchtime.

The agreement underscores the importance and effectiveness of unions in improving the lives of workers.

“We can say now that every time there is a problem, the workers come to the union because they always find that the unions are a real help,” said Eliacin Wilner, GOSTTRA organizer.

Unions are working to ensure that workers are aware of the program and able to access their benefits.

The agreement is the result of minimum wage protests by garment workers in January 2022. Fueled by frustration over three years without a minimum wage increase and the rising cost of basic necessities and services, workers at the SONAPI industrial park in Port-Au-Prince held a spontaneous protest to call for a wage increase.

The peaceful demonstrations extended into February and were met with police violence.

The protests led to negotiations between the government and a coalition of nine textile unions. The coalition’s advocacy resulted in an increase of the minimum wage from 500 gourdes ($4.82) per day to 685 gourdes ($5.85) per day.

Solidarity Center studies repeatedly have demonstrated the daily minimum wage is far less than the estimated cost of living in Haiti. Significant job losses due to supply chain disruptions have left most garment workers facing diminished working hours or layoffs, threatening their ability to provide for their families. These periods of income precarity are especially dire given that most low-wage garment workers lack savings.

Aug 8, 2022

Even as war rages in Ukraine, with daily bombings, food and medicine shortages and tens of thousands of displaced people crowded in cramped public spaces, the Ukrainian Parliament recently passed a series of laws that attack workers’ basic rights on the job and undermine the ability of unions to freely function.

“Instead of having some greater protection of labor rights, greater protection of the people who are baking bread, washing dishes or cleaning the streets, since March we faced very regressive labor reform in Ukraine,” says George Sandul, a Kyiv-based labor lawyer, on the latest episode of The Solidarity Center Podcast.

Sandul outlined a series of laws parliament recently pushed through as martial law limited the ability of union members to strike or protest the changes, and as many unions and their members are focused on providing humanitarian assistance.

‘Unions in Ukraine have literally invested everything to support their country—union offices and labor halls have become shelters and refugee support centers. In some cases, unions have even donated all their money,” says Solidarity Center Executive Director and Podcast Host Shawna Bader-Blau.

“And in return for their heroism, sacrifice and commitment to country, big business and their allies in parliament want to slash workers’ collective rights to bargain for better wages.”

Listen to the full episode here.

More Solidarity Center Podcasts!

Listen to this episode and all Solidarity Center episodes here or at Spotify, Amazon, Stitcher, or wherever you subscribe to your favorite podcasts.

Download recent episodes:

Jul 18, 2022

Despite often heroic efforts to deliver food under war conditions, Bolt delivery drivers in Kyiv, Ukraine, have seen a 60 percent cut in wages—and they are demanding the company take immediate action to boost wages and provide vehicle maintenance support.

Prohibited from striking while Ukraine is under martial law, the delivery drivers gathered recently at Bolt’s office in Kyiv to present the company with their demands, which include an increase in minimum payments from 84 cents per order to $1.36 per order, and a boost in per-kilometer pay from 24 cents to 41 cents to compensate for the rise in inflation.

“Our wages have been cut to the minimum,” a driver stated at the gathering. “Now they are trying to force us to work for pennies. It is almost impossible to feed one person on such a wage.”

Another driver said he must “work 14 hours a day, 27 days a month” to survive.

The app-based workers also are urging the company to provide free or low-cost repair and maintenance for their vehicles, most of which are bicycles and motorbikes.

The app-based workers also are urging the company to provide free or low-cost repair and maintenance for their vehicles, most of which are bicycles and motorbikes.

“Bolt Food does not compensate our work expenses in any way,” a driver said. “We bear the risks ourselves. We have to maintain transport at our own expense, we have to pay for fuel, spare parts—and all prices just skyrocketed but our wages were further reduced. These costs reach 70 to 75 percent of income at current prices.”

In addition, workers want Bolt to re-open several app features, such as one that enables drivers to see the client’s address before they accept the job. If the restaurant where they pick up the food is only a few blocks from the client, they only are paid for the short distance from the restaurant to the client’s location, even if they drive miles to get to the restaurant.

Earlier this year, Bolt Food riders in Lviv raised similar demands with the company after Bolt cut wages so drastically workers could not afford gas for their vehicles. Many Ukrainians relocated during the war to Lviv, a relatively safe haven near Poland’s border, and delivery drivers say Bolt took advantage of their plight as they desperately sought jobs to support their families. The delivery drivers won a wage increase July 5 that includes a boost in the amount drivers receive when delivering food during peak times, weekends, late hours and in bad weather, a feature Kyiv delivery drivers also are seeking.

Massive Job Loss and Attacks on Worker Rights

The company’s cutback in wages comes as more than one-third of jobs in Ukraine have been lost since the beginning of the war in February, according to an International Labor Organization report in May. The ILO projected job losses to reach 7 million, or 43.5 percent of the workforce, if the war continues.

Even as the war has decimated jobs and the economy, Ukraine’s parliament passed a law that would significantly erode employees’ rights in areas covering working hours, working conditions, dismissal and compensation after dismissal. The law makes it legal to fire employees who are on sick leave or vacation and allows employers to increase the work week from 40 hours to 60 hours, shorten holidays and cancel additional vacation days. A union’s rights also would be severely curtailed and employers would have the right to unilaterally cancel collective bargaining agreements.

Lawmakers say the legislation would apply only during war. But George Sandul, a lawyer with the Ukrainian worker rights organization Labor Initiatives, says unions and legal experts fear the law will not be revoked.

The legislation did not stem from the war. Similar proposals were pushed months before Russia invaded Ukraine, with the parliamentary committee for social policies and the Ministry of Economy pressing to radically change labor law to favor employers and restrict union rights.

The app-based workers also are urging the company to provide free or low-cost repair and maintenance for their vehicles, most of which are bicycles and motorbikes.

The app-based workers also are urging the company to provide free or low-cost repair and maintenance for their vehicles, most of which are bicycles and motorbikes.