Oct 7, 2022

Databases of legislation, compilations of laws and successful practices that advance worker rights, trainings, and coordination with allied organizations are some of the suggestions members of the International Lawyers Assisting Workers Network (ILAW) recommended the organization pursue.

Madhulika Tatigotia. Credit: Solidarity Center

Meeting in breakout groups on the first day of the ILAW Network Global Conference, worker rights lawyers shared their work on, and requested support in, areas involving the global supply chain, informal economy work, employment discrimination, migrant worker rights, workplace safety and health and violence and harassment in the world of work.

“There is a need for more cooperation and sharing of litigation strategies and legal expert opinions across countries,” said Madhulika Tatigotla, a worker rights lawyer from India, who reported back to the afternoon plenary session on recommendations for improving worker rights in global supply chains.

She said ILAW members noted the need for a database of supply chain cases and a map of supply chains to better understand the networks. The group also proposed ILAW Network hold webinars on European Union due diligence laws and create a report on business and human rights litigation around supply chains modeled after ILAW’s 2021 report, “Taken for a Ride: Litigating the Digital Platform Model.”

More than 130 labor lawyers from 42 countries are meeting in Brussels October 7–9 for the second global conference of the International Lawyers Assisting Workers (ILAW) Network, where members set an ambitious agenda for advocacy, litigation and education.

The Solidarity Center launched the ILAW Network in December 2018 as a global hub for worker rights lawyers to facilitate innovative litigation, help spread the adoption of pro-worker legislation and defeat anti-worker laws.

Addressing Violence at Work

Furaha Joy Sekai Saungweme. Credit: Solidarity Center

“There are many grounds for discrimination and this provoked a very rich debate,” said Viviana Osoro Prez, Solidarity Center Equality and Inclusion Department director, who shared participants’ input from the employment discrimination breakout. “We looked into how important it is to create wider alliances between different movements, and for all legal assistance to be more connected with unions and society.” The group suggested ILAW Network create a repository of clauses from collective bargaining agreements on violence and harassment at work and trainings on discrimination in the workplace.

Violence and harassment (GBVH) in the world of work also is being addressed through the International Labor Organization Convention 190, and ILAW members in the GBVH breakout discussed how they are working to incorporate its provisions in collective bargaining agreements and pushing for leave from work for those who have experienced domestic violence. Reporting back from the GBVH group, Furaha Joy Sekai Saungweme, a worker rights lawyer in Tanzania, noted a need for information sharing by countries that have ratified C190 and also on collective bargaining clauses and legal reform efforts addressing GBVH.

Coordination of Best Practices

Teresa Marchiori who, with J.J. Rosenbaum at GLJ-ILRF, led the breakout on the informal economy, reported the need for coordination of best practices in winning rights for informal economy workers, nearly none of whom are covered by labor laws in most countries. She noted an invitation from StreetNet International, a global network of workers in the informal economy, to join them in sharing legislative initiatives.

Michael Felsen. Credit: Solidarity Center

Migrant workers are 5 percent of the workforce but comprise 15 percent of workers in forced labor,” said Neha Misra, Solidarity Center Global Lead for Migration and Human Trafficking. Misra and Sarah Mehta from the Migrant Justice Institute reported back from the migrant worker breakout meeting where members suggested ILAW spearhead draft laws on labor migration and look at issues such as how best to ensure migrant workers have the same legal rights as all workers. Fundamentally, “they must have legal rights to form unions and collectively bargain to improve their working conditions,” Misra said.

Worker rights lawyers reported a wide range of health and safety issues, many occurring in new forms of work such as digital employment and telework, said worker rights attorney Michael Felsen. “One of the key takeaways is that we all want ILAW to assist in getting governments to do better law enforcement around safety and health, push goverments to protect workers through new and current legislation, research successful clauses in collective bargaining agreements on safety and health and push governments to enact and enforce safety and health legislation.

Oct 7, 2022

Opening the ILAW Network Global Conference 2022, Solidarity Center Rule of Law Director and International Lawyers Assisting Workers Network (ILAW) Chair Jeffrey Vogt cited the many challenges facing workers—and reviewed the significant achievements ILAW Network members have accomplished to ensure workers achieve their basic rights on the job.

Jeff Vogt, Solidarity Center Rule of Law director and ILAW Network chair, opens ILAW Network Global Conference. Credit: Solidarity Center

“We’re seeing that every effort is being made to try to find ways to undermine the rights of workers—there are so many new ways that workers are confronting, extreme obstacles to basic dignity and rights on the job,” he said. Vogt detailed the concrete ILAW Network’s concrete achievements since the organization’s first conference in 2019, which included the January 2022 decision by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights that affirmed workers’ right to strike in Guatemala.

More than 130 labor lawyers from 42 countries are meeting in Brussels October 7–9 for the second global conference of the International Lawyers Assisting Workers (ILAW) Network, where members set an ambitious agenda for advocacy, litigation and education.

The Solidarity Center launched the ILAW Network in December 2018 as a global hub for worker rights lawyers to facilitate innovative litigation, help spread the adoption of pro-worker legislation and defeat anti-worker laws.

Workers and Their Unions Key to Winning

In the first plenary session, “The Future of Workers—Labor and Technology,” panelists discussed how workers are standing up to the challenges of workplace surveillance, telework and app-based work—new versions of employment exploitation that employers have practiced for decades.

Martha Dark, Foxglove. Credit: Solidarity Center

“Big tech companies have spent decades perfecting the art of creating cultures of secrecy that fail to provide proper jobs, but these issues are not specific to the tech space,” said Martha Dark, co-director of Foxglove, a United Kingdom-based nongovernmental organization seeking to make tech fair.

Dark was joined by Daniel Motaung, a former Facebook moderator who was fired for forming a union in Kenya and is now challenging the move in court along with a case arguing Facebook must provide decent working conditions

“I moderated content that was very difficult to speak of, including the live beheading of a woman,” he said. The horror he witnessed gave him post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a mental heath condition common among the 15,000 social media monitors around the world who suffer such health issues without adequate protection from tech companies, Dark said.

Yet Facebook moderators in Kenya are paid as little as $1.50 an hour, according to a TIME magazine investigation.

“Worker rights are essential to empower tech workers to fight back against the dominance of tech attacks,” Dark said. “Unionizing across the world is a meaningful strategic check on corporate power.”

App-Based Workers Do Not Need to Trade Flexibility for Rights

Ruwan Subasinghe, ILAW Network Board member. Credit: Solidarity Center

Job misclassification is one of the fundamental issues delivery drivers and other app-based workers face, said Ruwan Subasinghe, an ILAW Network Board member. When workers are classified as independent contractors, they have no guaranteed wage, paid compensation for workplace injury or illness, or other fundamental labor rights.

“Misclassification isn’t new, but with platform workers it uniquely affects workers of color and migrants and has a major impact on income and safety and health,” he said.

Worker rights lawyers are pushing for legislation to re-classify platform workers, arguing that they are not independent contractors because their employment relationship creates a form of dependency, Subasinghe said.

While tech companies argue that workers would lose flexibility in work schedules if they are classified as employees, worker rights on the job and flexibility are not mutually exclusive, he said, citing the Danish union 3F’s collective bargaining agreement with Just Eat. The contract includes rest breaks between shifts, pay for workers when they are logged off and the option of asking for two-hour wage slots.

ILAW Network Board Member Monica Tepfer reviewed an International Labor Organization study that indicated how existing laws, such as equal protection, can be used to address issues arising in new models of work, such as telework and digital work,

ILAW Network Board Member Monica Tepfer reviewed an International Labor Organization study that indicated how existing laws, such as equal protection, can be used to address issues arising in new models of work, such as telework and digital work,

“Work is not a commodity but collecting data can become a commodity,” and it is essential to work through laws and collective bargaining to ensure worker data is protected as well, she said.

Barbara Cernusakova from UNI Global Union, shared legislative examples of how workers in Europe are bargaining and litigating for their rights to privacy, health and safety and decent workplaces.

Improving Worker Rights in Honduras, Nepal and Uganda

In a second morning panel, ILAW Network lawyers from Honduras, Nepal and Uganda described how they are implementing strategic litigation to improve worker rights.

In Nepal, Shom Luitel is pushing for legislation that would expand the definition of forced labor and would include compensation for targets of forced labor and uniform punishment for offenders, and ensure education and rehabilitation for children in forced labor.

Luitel is one of three recipients of the ILAW Network’s Litigation Fund established in July to provide modest financial assistance to promote or defend the rights and interests of workers and unions.

ILAW Network Member Robinah Kagoye described work in Uganda seeking to ensure labor law protections for workers in the informal economy, who comprise 87 percent of the workforce but are not covered by the country’s labor laws. Without such coverage, they have no safety and health protection, no paid sick leave and are not allowed to form unions—yet they create 50 percent of the country’s economy.

Kagoye says that police are now undergoing rigorous training on worker rights and must use body cameras. A street vendor bill has been introduced in Parliament, and Kagoye and others in the campaign for informal worker rights are in ongoing dialogue with the government on those rights.

In Honduras, Maria Elena Sabillion described litigation seeking compensation for garment workers who were suspended from work during the pandemic. Some 31,000 workers were suspended under Honduran laws, but the suspension did not comply with due diligence, she says. Companies used the suspension to lay off union leaders and workers who got workplace injuries, she said, earning huge profits while workers suffered with no wages.

Participants at the ILAW Network Global Conference also will evaluate progress since the first ILAW Conference in 2019, Speakers include Clément Voule, Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association for the United Nations, and International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) General Secretary Sharan Burrow.

Stop back here for regular coverage of ILAW Network Global Conference and follow live updates on Twitter @ILAW_Network

Oct 4, 2022

.

More than 140 labor lawyers from 42 countries are gathering in Brussels October 6–9 for the second global conference of the International Lawyers Assisting Workers (ILAW) Network, where they will exchange legal strategies for the promotion and defense of the rights and interests of workers and trade unions, explore coalitions with allies and plan the network’s strategic goals for the next two years.

Participants at the ILAW Network Global Conference also will evaluate progress since the first ILAW Conference in 2019, where members set an ambitious agenda for advocacy, litigation and education. Speakers include Clément Voule, Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association for the United Nations and UNI Global Union General Secretary Christy Hoffman.

Benson Upah, an ILAW Advisory Board member and coordinator in Nigeria, says one of the network’s accomplishments since the last conference is building membership—from some 350 members to more than 800 members in dozens of countries. The ILAW Network also has hired regional coordinators in Africa, the Americas, Asia and East Europe/Central Asia, fulfilling one of the members’ key recommendations at the first conference.

“The growth of the ILAW Network worldwide represents a significant step toward improving worker rights in areas of strategic litigation, bolstering labor legislation and holding governments accountable to their obligations under international labor standards,” says Solidarity Center Rule of Law Director and ILAW Network Chair Jeffrey Vogt. “ILAW lawyers proactively represent workers and unions and are a key part of workers’ struggles for rights, dignity and justice on the job.”

The Solidarity Center launched the ILAW Network in December 2018 as a global hub for worker rights lawyers to facilitate innovative litigation, help spread the adoption of pro-worker legislation and defeat anti-worker laws.

Far-Reaching Support for Worker Rights

ILAW litigation supporting worker rights is both broad and finely targeted. One of the network’s key recent victories, says Mónica Tepfer, an ILAW Board member, is the January 2022 decision by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights that affirmed workers’ right to strike in Guatemala. The ILAW Network filed a 40-page amicus brief successfully arguing that a series of court rulings denying workers’ right to strike if two-thirds vote to do so violated the country’s Labor Code.

ILAW assisted the Georgian Trade Union Confederation in developing a report, “The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Women’s Labor Rights,” which included recommendations that ILAW and Georgian trade unions are now advocating for at the national level to improve worker rights protections for women.

In Uganda, ILAW provided legal support for more than 170 street vendors who were arrested following eviction orders and charged with offenses such as selling goods without a license and public nuisance. ILAW worked in collaboration with unions organizing in the informal economy and with partners such as WIEGO, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung and StreetNet International.

ILAW from the beginning has worked closely with partners globally. “The collaboration between the ILAW Network and the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC)—a founding member and board member of ILAW—provides ITUC affiliates the best legal advice and assistance to advance labor right and I expect that that collaboration to continue and to deepen,” says Paapa Danquah, ILAW Board member and ITUC Legal Director.

A Push for Platform Worker Rights

Along with a focus on workers in the informal economy such as street vendors, ILAW has engaged in extensive research and legal support on behalf of app-based workers. For instance in Nigeria, ILAW backed litigation advancing the rights of drivers hired through digital platforms such as Uber and Bolt. The drivers are misclassified as independent contractors rather than as employees and so do not receive paid sick leave, compensation for workplace injuries or other basic protections provided by the country’s labor laws.

ILAW also researched gig workers’ labor rights protection in Central Asia, looking into the digital platform markets and identifying drivers’ working conditions. In addition, ILAW produced to the report, “Taken for a Ride: Litigating the Digital Platform Model,” in response to requests from ILAW Network members for comparative analysis on litigation against digital platform companies around the world. The network also compiled the Database on Standards and Decisions on Digital Platform Work in Latin America that includes draft laws, legislation and decisions regarding digital platform work.

In July, the ILAW Network launched the Litigation Fund to provide modest financial assistance to promote or defend the rights and interests of workers and unions. Supported by the Open Society Foundations, the fund currently is supporting litigation in Nepal, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

Additional ILAW network accomplishments since the 2019 conference include:

- Setting up an online member-accessible database with expert and member-sourced recommended legislative or union contract provisions addressing workers’ key issues.

- Publishing the Global Labour Rights Reporter, a law journal offering a forum for labor and employment law practitioners globally, including ILAW Network members, to grapple with the legal and practical issues that directly affect workers and their organizations.

- Launching a webinar series to provide members learning opportunities on topics such as workers’ rights on digital platforms, promotion of International Labor Organization Convention 190 to end violence at work, and migrant workers’ rights.

Since the last ILAW conference, “the visibility of the Network has been significantly raised among the labor rights lawyers, scholars and others interested in the labor rights related issues,” says Raisa Liparteliani, ILAW Network board member. “In my opinion the periodic review, the Global Labour Rights Reporter (GLRR) positively affected to this process.”

The 2022 conference offers members a renewed opportunity to shape the coming years of the network and strategize on addressing emerging issues such as impacts of climate change on labor, the future of work, the emergence of artificial intelligence in managing workers and the new challenges in the changing workplace.

Stop back here for regular coverage of ILAW Network Global Conference and follow live updates on Twitter @ILAW_Network.

Sep 26, 2022

.

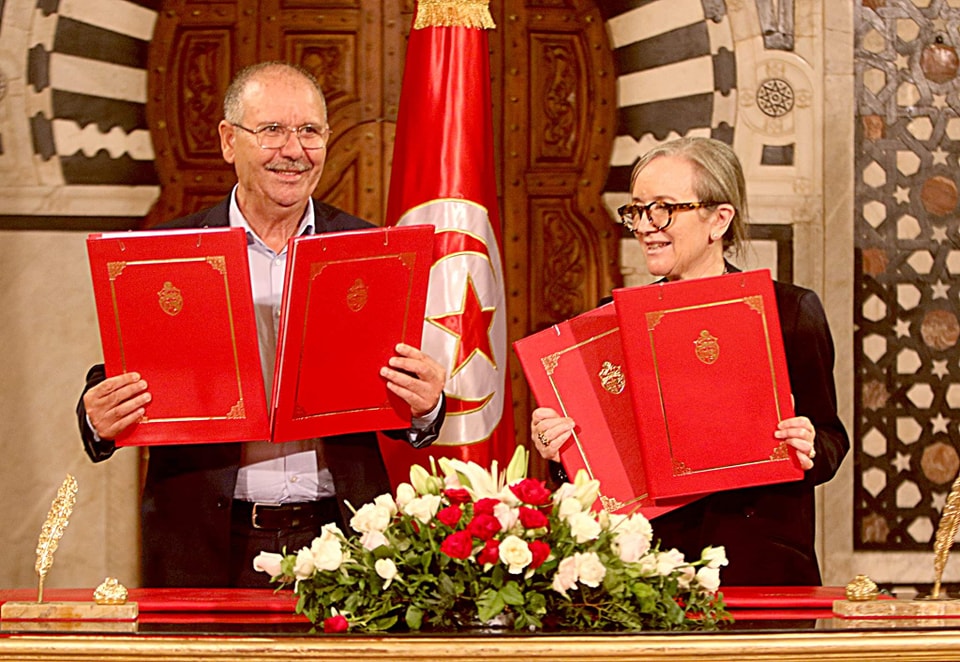

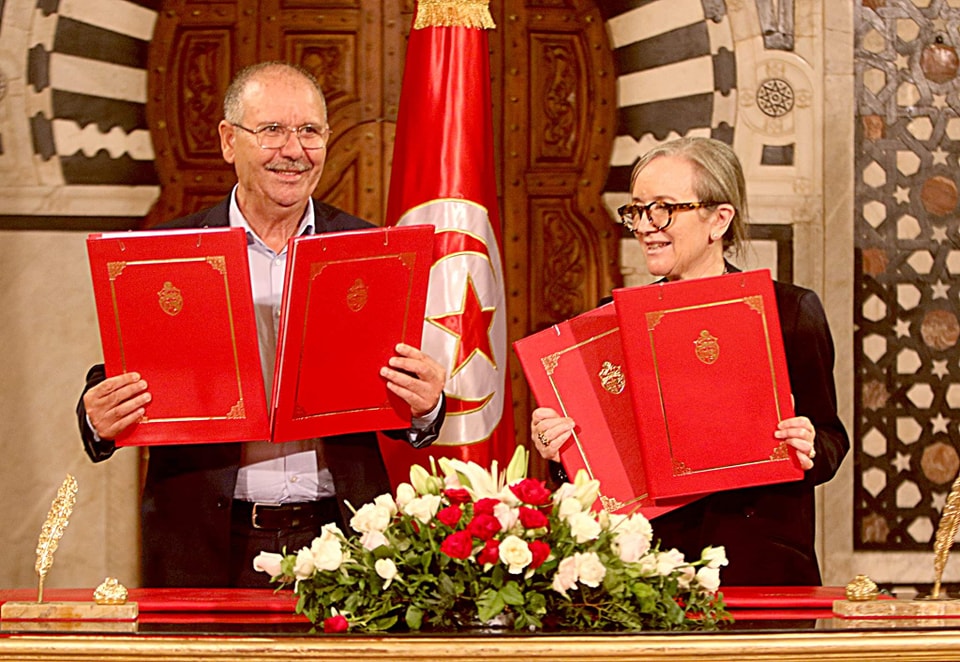

Public employees across Tunisia won a 5 percent wage increase over three years plus financial benefits through revisions of the tax code, following a general strike and weeks of difficult negotiations, according to the Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT). The agreement also increases the guaranteed minimum wage by 7 percent.

“Our objective through this agreement is to establish social peace and to ease the tense social climate, in view of the very difficult social situation and the deterioration of purchasing power,” UGTT General Secretary Noureddine Taboubi told Agence France Press.

The agreement restores key union rights by guaranteeing the right to free collective bargaining negotiations. UGTT had called on the government to adhere to a December 2021 agreement in which it will negotiate with unions on policies affecting workers.

The September 14 pact follows a one-day general strike in June by hundreds of thousands of public employees—including transportation workers, utility workers and health care workers from 159 state institutions and public companies across Tunisia.

Workers protested deteriorating economic conditions and government efforts to freeze public employee wages, part of the government’s attempts to secure financial assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The IMF recently indicated the loan is expected to be between $2 billion and $4 billion over three years.

A series of Tunisian governments have been unable to improve the economy or address the jobs crisis. More than 16 percent of people are unable to find work while more than 38 percent of young workers were unemployed in 2021.

People across Tunisia are taking to the streets in recurring popular protests as they struggle with high inflation, food shortages and government increases in the price of basic goods like fuel, and cooking gas cylinders, which it increased by 14 percent.

Solidarity Center works closely with the UGTT which, with its nearly 1 million members, continues to fight for their democratic freedoms in difficult conditions as workers join together and negotiate collectively over their pay, working conditions and workplace decisions.

Sep 13, 2022

This September 15, International Day of Democracy, people in more and more countries are faced with growing authoritarianism and shrinking space to freely participate in civil society.

Yet authoritarian regimes can be countered and democracy fostered through the actions of vibrant labor movements, according to two lawyers and guests on the latest episode of The Solidarity Center Podcast.

“There’s extensive research and empirical studies on the working class and unions and the critical role that they’ve played in forging and defending democracies,” Cornell University law professor Angela Cornell tells Podcast host and Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau. “The organized working class was the primary carrier of democracy, playing a decisive role in the forging of democratic regimes and the most consistently pro-democratic force, which pushed forward and fought for democracy against the resistance of other class actors.

Unions, in Coalition, Advance Democracy in Colombia

A recent example is unfolding in Colombia, where a diverse coalition of unions, young people, members of Black and Indigenous communities and others joined together to craft changes to the country’s laws that reflect the needs of workers and all communities historically marginalized by the government. Their efforts resulted in the election of a progressive slate of candidates in August, including Francia Márquez, a former housekeeper, union member and Colombia’s first Black vice president.

“We had focused so many of our efforts on changing, on getting to pick something different in over 200 years of our republic,” says labor lawyer and union activist Mery Laura Perdomo. “We focused on taking the streets. Every union became essential where the campaign was discussed. They became forums for the discussion of politics, on how to change the country. In every square you would see students talking to the citizens about the different candidates, about the different political programs and why this was important.”

Perdomo, who is on staff with the Solidarity Center and International Lawyers Assisting Workers (ILAW) network, and Cornell, who recently co-edited the Cambridge Handbook of Labor and Democracy, describe how unions’ role in reducing economic inequality, strengthening the social safety net and uniting diverse groups create more democratic outcomes.

Listen to the full episode.

MORE SOLIDARITY CENTER PODCASTS!

Listen to this episode and all Solidarity Center episodes here or at Spotify, Amazon, Stitcher, or wherever you subscribe to your favorite podcasts.

Download recent episodes:

Sep 7, 2022

Haiti garment workers should be paid four times their current salaries just to keep pace with the cost of living, a new Solidarity Center study finds. The High Cost of Low Wages in Haiti: A Living Wage Estimate for Garment Workers in Port-au-Prince, determined that based on the current minimum wage ($781 per month), workers spend almost a third (31.39 percent) of their take-home pay on transportation to and from work and a modest lunch to sustain their labor.

“The Haitian government must ensure that workers earn life-supporting wages,” according to the study, which recommends the Haiti government increase the minimum wage to a living wage and ensure that “workers’ rights to freedom of association and collective bargaining are fully respected, so that workers are empowered to negotiate wage increases and improve working conditions with employers.”

The report builds on two previous living wage studies the Solidarity Center published in 2014 and 2019 and an unpublished 2011 living wage report that demonstrate the daily minimum wage for garment workers is far less than the estimated cost of living—including in 2019, when inflation was 18.7 percent. The latest data from May 2022 show Haiti’s inflation rate at 27.8 percent.

Garment Worker Unions Seek to Build on Wage Gains

Garment workers say that despite recent improvements in benefits, the current wage is far from what they need. In August, Haitian garment workers in Port-au-Prince scored a victory after a coalition of unions negotiated an agreement with the government to provide garment workers with transportation and food stipends. The government made improvements in February, after garment workers and their unions held protests in January demanding a living wage in line with the Haitian Labor Code, which stipulates that if the inflation rate exceeds 10 percent, the wage is to be adjusted.

Haitians, especially the most marginalized, are suffering from a wave of violence this year that, along with fuel shortages, impact transport along Haiti’s roadways, preventing many apparel workers from getting to work and materials from arriving at factories. After paying a significant portion of their wages for transportation to work—and enduring an often-dangerous journey—some apparel workers are sent home without pay because the factory has not received supplies necessary for production, according to the report.

The country’s garment industry is the largest source of formal employment for workers in Haiti, where the majority of 58,571 garment workers are women and often the only wage earners for their families. Yet they routinely face worker rights abuses, including occupational safety and health violations and wage theft. Factory management frequently do not pay into the national health insurance system for occupational injury, sickness and maternity (OFATMA), failures that even have led to worker death.

To compile the study, three data collectors in May and June surveyed the prices of products and services for a locally appropriate basket of goods, including housing, transportation, food and education and used the standard 48-hour work week to determine cost of living needs.

ILAW Network Board Member Monica Tepfer reviewed an International Labor Organization study that indicated how existing laws, such as equal protection, can be used to address issues arising in new models of work, such as telework and digital work,

ILAW Network Board Member Monica Tepfer reviewed an International Labor Organization study that indicated how existing laws, such as equal protection, can be used to address issues arising in new models of work, such as telework and digital work,