Jul 27, 2017

In Mombasa, the labor broker’s announcement that jobs were available in Saudi Arabia resonated with Maria Makori Mwentenje.

“We were very poor. We had two children,” (age 10 and 1), Makori says, describing why she and her husband agreed that she should seek work in the Saudi Arabia. “We tried a small business and selling food, but that didn’t work. And there were no casual jobs available. We were hustling every day, but some days there was not enough to feed the family.”

Makori signed up with the labor broker but was not given a contract nor told her duties. Only at the airport did she learned she would be paid 18,000 Kenya shillings ($172) a month rather than the 23,000 ($221) she was promised. But even at that rate, she had to take a chance—it was not possible to earn that much in Kenya. She boarded the plane.

When she arrived in Saudi Arabia, she and other women traveling for work were taken to a room where their passports and travel documents were confiscated. Under the kefala system in Arab Gulf countries, migrant workers are tied to one employer, and it is illegal for them to get another job in the country. To ensure they do not leave, employers typically take their passports and often their mobile phones.

In Saudi Arabia, Makori was required to care for four children, including a baby. Working around the clock, her employer expected her to wake at all hours of the night to tend to the baby and still rise at 6 a.m. to prepare the family’s breakfast and get the children ready for school.

During her last pregnancy, Makori had developed hypertension, and in Saudi Arabia, the long hours, stress and difficult tasks exacerbated her condition. She experienced frequent headaches, and her body started to swell. Rather than take her to a doctor, her employer forced her to take pills, and she did not know what they were.

She was sexually harassed from the time she first walked into the employer’s house. When she contacted her husband and told him about the abuse, her husband went to the labor broker and asked why he sent his wife to such an employer. Rather than take steps to ensure Makori’s safety, the labor broker verbally abused her husband.

At one point, when she was too ill and tired to work, she told her employer she needed to rest. Enraged, the employer’s daughter entered the tiny space where Makori slept and after screaming at her, threw an iron at Makori, barely missing her head.

Fearing for her life, Makori fled to the police, where she was fortunate to encounter an officer who forced the family to return her passport and gave her money to travel. Unpaid for six months of work, she was grateful to return home with her life.

Jul 20, 2017

When Mwahamisi Josiah Makori arrived in Saudi Arabia in 2014 at the home of her employer, she was given 20 minutes to rest before beginning her duties as a domestic worker. Her employers held their noses when they greeted her and made her shower outside before allowing her in the house.

Her responsibilities involved cleaning two homes, including that of the employer’s mother-in-law. She was required to take care of the children, and when they spit on her, her employer told her not to complain. She was up all night caring for the baby and by 6 a.m., preparing the family’s breakfast.

She was given a torn, dirty mat to sleep on, and when she requested a new mat, her employer refused, telling her she was only there for work. In the middle of her tasks, she was required to stop and flush the toilet after a family member used the bathroom.

Makori was required to hold the baby throughout the day as she cooked, cleaned and cared for the other children. One afternoon, when she put the baby down to store groceries, the baby crawled to a cabinet. Alarmed, she called out. Her employer began beating her, saying she was making the baby nervous. They took her to the police authorities and told them she slept all day and refused to work.

She finally was able to convince the police of her plight, and an officer told her employer to pay her way home. The employer refused, but the employer’s mother-in-law paid her way to Kenya.

In Kenya, Makori had struggled to support her three children as a single mother. She was desperate for paid employment when her best friend introduced her to a labor broker who was traveling from village to village. Makori could not afford to pay her children’s school fees, and says she felt she had no choice but to leave the country for work.

After three months of nearly non-stop labor in Saudi Arabia, Makori returned to Kenya. Without pay.

Jul 13, 2017

Over the past five years, Alice Mwadzi signed up 200 domestic workers with KUDHEIHA union in Kenya and helps women seeking to migrate abroad, where conditions can be brutal, get jobs in their own country.

“I go door to door to give them hope,” she says with pride.

Jul 12, 2017

Sok Rathana, 19, has been a domestic worker in Cambodia for two years, working 100 hours a month for $70 while attending high school. Her family is poor, and her mother also is a domestic worker.

As in many countries, domestic workers in Cambodia are not covered by labor laws and so have no minimum wage, safety and health protections or other basic employment benefits.

As Sok says, “I don’t think I have full rights as a domestic worker.”

May 10, 2017

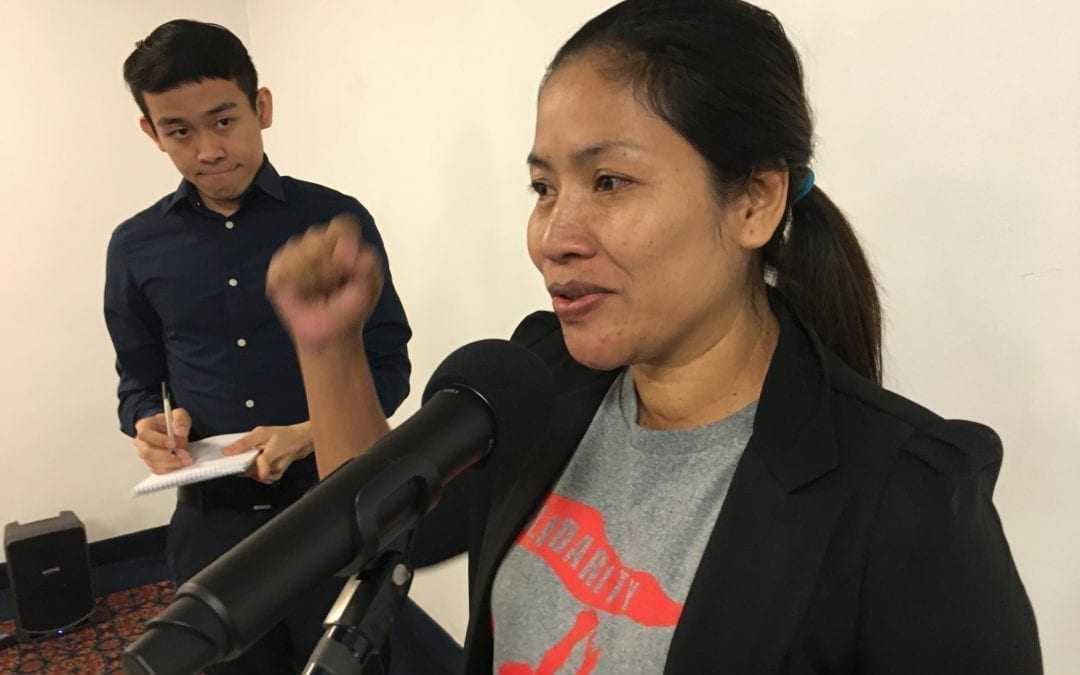

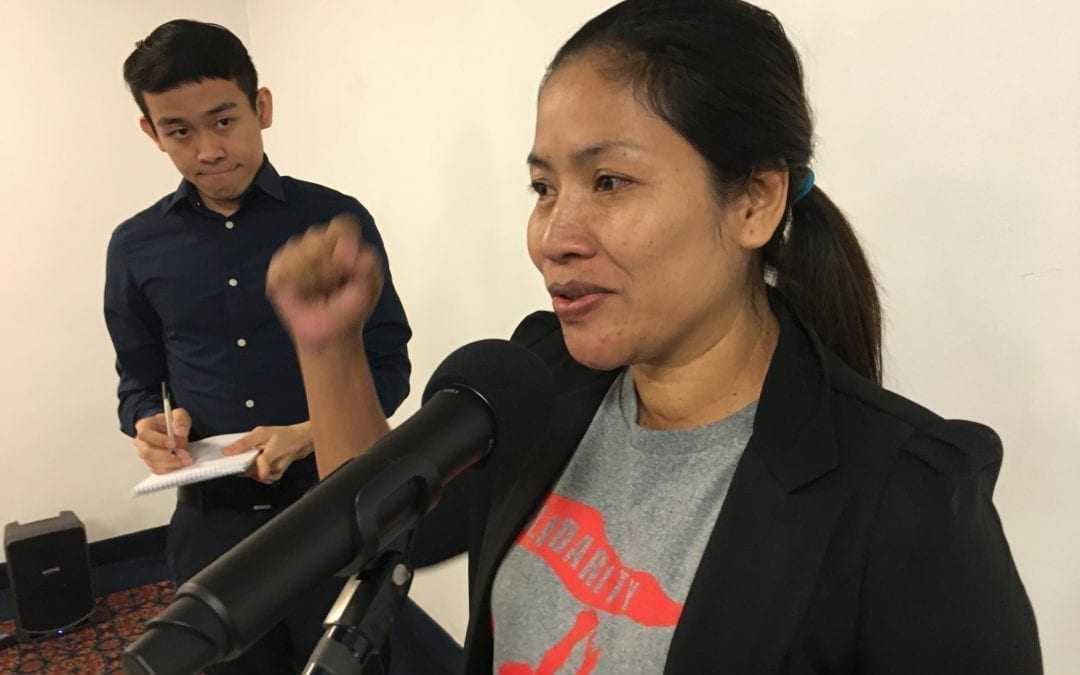

Sophorn Yang, president of the Cambodian Alliance of Trade Unions (CATU), helps lead national campaigns to win a fair wage and to protect workers’ fundamental rights in the face of restrictive Cambodian trade union laws.

Despite receiving threats because of her activism, she remains committed to her mission of bringing more women workers into union leadership, and to the leading the Cambodian worker movement to achieve a nationwide living wage.

“My name is Yang Sophorn, and I am president of Cambodian Alliance of Trade Unions (CATU). I would like to tell people about the living condition of workers in Cambodia. We have seen that their living situation is very difficult. Garment workers work long hours, from Monday to Saturday and Sunday, and they work between 10 and 12 and 14 hours per day.

“Their wage does not correspond to the needs of their living expenses, which means, they only get $150 a month when they work for eight hours per day. So, generally they try to ask for overtime, etc. Therefore (to sum up), these are the difficulties and hardships of garment) workers in Cambodia.”

(Read more about Yang here.)