Apr 17, 2019

On a recent Friday, the only day off for Bangladesh garment workers—if they get a day off—I went to visit workers at their homes to better understand how the people who stitch our clothes live their lives. Walking through the puzzling narrow alleys, I entered a tin shed-like building. A corridor tore through the center and on each side were rooms for families. It was in one of these dimly lit rooms where I met Konika, who worked as a sewing operator in a nearby garment factory in Gazipur. In the tiny space where she lived with two children and her husband, she revealed the conditions at her workplace.

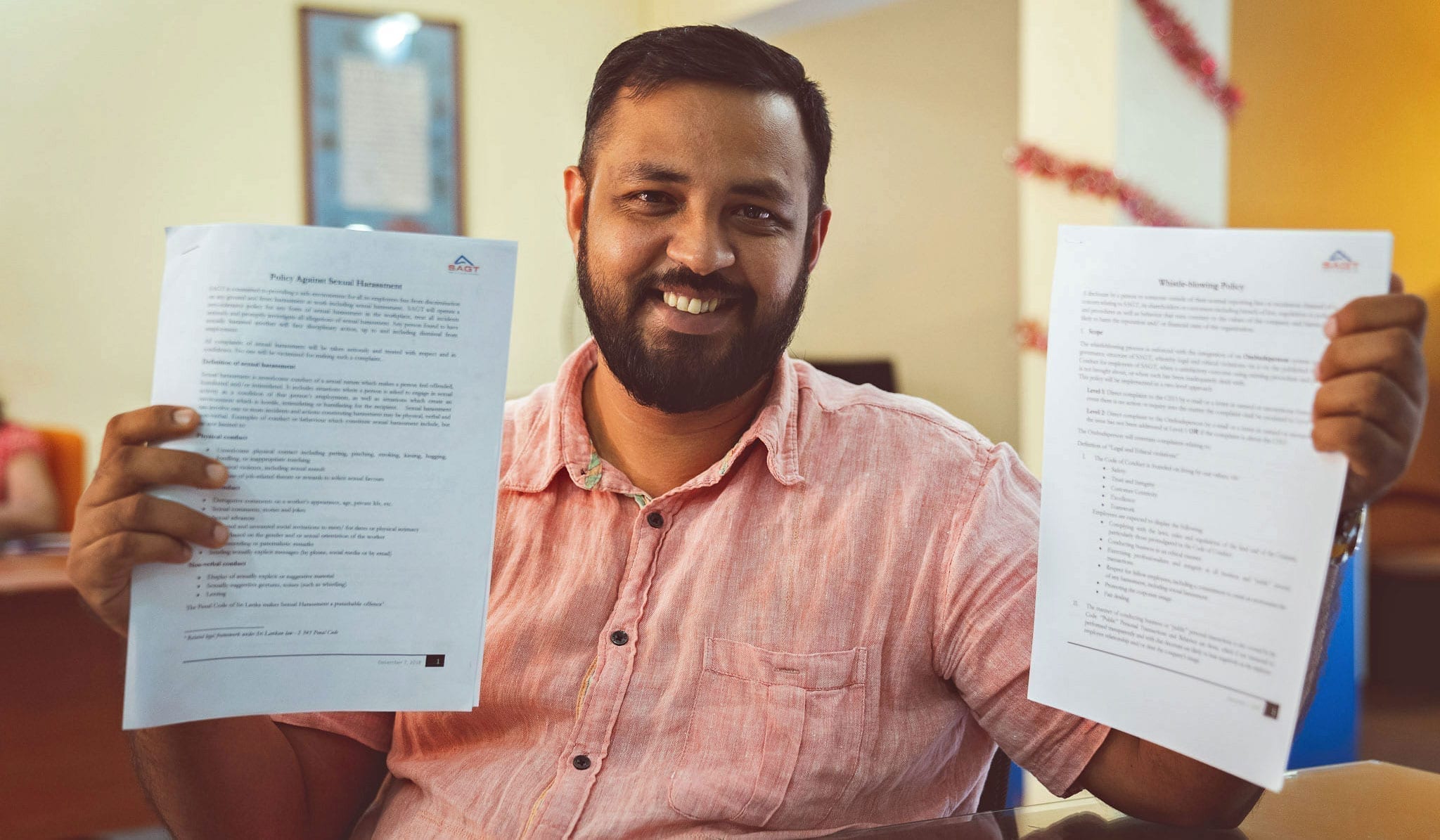

A garment factory in Gazipur. Credit: Solidarity Center/Istiak Ahmed Inam

“We are under intense pressure to meet the target production,” she says. “I used to produce 70 pieces an hour but now, after our minimum wage has been increased by the government, I must produce 90 pieces. I have to think twice if I want to use the washroom. What if I miss my deadline? What if my production manager sees me? I rest only if there’s a problem with my machine and am lucky if the mechanic is not close by.”

Worker Safety under Threat Again

Six years after the deadly April 24, 2013, Rana Plaza building collapse killed 1,134 garment workers and injured hundreds more, the government is on the verge of rolling back international safety inspections even as employers and the government are blocking workers’ ability to exercise their right to form unions to improve working conditions.

Disasters like Rana Plaza or the 2012 Tazreen Fashions fire, which together killed more than 112 garment workers, prompted global outrage and mobilized workers in protest of unsafe and deadly working conditions, forcing major fashion brands and Bangladesh suppliers to address safety issues. As a result, unions, suppliers and many international brands formed the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, a binding agreement that helped make many garment factories safer. Despite its success, however, the accord may be dismantled, leaving workers at the mercy of a system unprepared to improve factory safety, according to a recent report.

Meanwhile, fashion companies often send their own inspection teams to factories, but the effectiveness of these visits is debatable.

“Our managers make us tell the foreigners [safety inspectors] we don’t work until 10 p.m., that we receive our wages regularly and we even receive our doctor’s fees. None of this is true,” says Konika. On many occasions, the inspection team strolls around the factory, only gathering data from factory management and not from the workers, thus releasing inaccurate reports.

Konika and her co-workers face odds that would dishearten many: factory owners escalating pressure to produce and depriving workers of their basic rights, and corporations wearing a mask of “doing all they can” for workers, while in fact, doing nothing.

Yet Konika, on her day off, enjoys time with her family, despite recognizing the injustices she is likely to face tomorrow.

Apr 12, 2019

In a historic achievement, delegates to the 11th Congress of Brazil’s garment worker union federation, CNTRV (National Confederation of Clothing Workers) last week voted for gender parity in leadership and adopted a pro-women’s rights agenda.

The union achieved parity not only in the overall number of women and men in leadership, but also in its top executive positions.

“Women are empowered at the highest levels in the organization,” said CNTRV President Cida Trajano.

In partnership with the Solidarity Center, CNTRV in recent years ran a nationwide women’s leadership project, preparing women workers to assume leadership positions, according to Trajano.

“This is proof that the effort to form and organize feminist activism is worth it,” she said.

Over the next four years, CNTRV will focus on a pro-women’s rights agenda, including developing programs to combat gender-based violence at work and empower women workers; allow greater space for feminist agendas in communications; consult with women leaders and activists when developing recommendations for public policies affecting women; and expand women’s participation in collective bargaining and wage negotiations.

The Solidarity Center supports women workers seeking greater voice at the workplace across a range of employment sectors in Brazil, including the chemical, garment and hospitality industries, and domestic work. Together with the CNQ (National Confederation of Chemical Workers) CNTRV and CONTRACS (National Confederation of Service and Retail Workers), the Solidarity Center conducts trainings and campaigns to equip women to advocate for safer working conditions and more equitable salaries on the job, and to assume more active leadership roles in their unions.

Apr 4, 2019

Union members in Colombo, Sri Lanka, successfully lobbied for a safer workplace by convincing their company to improve policy guidelines to help prevent gender-based violations in the workplace.

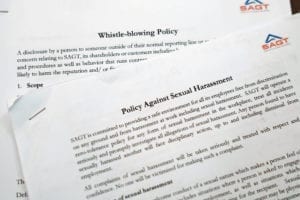

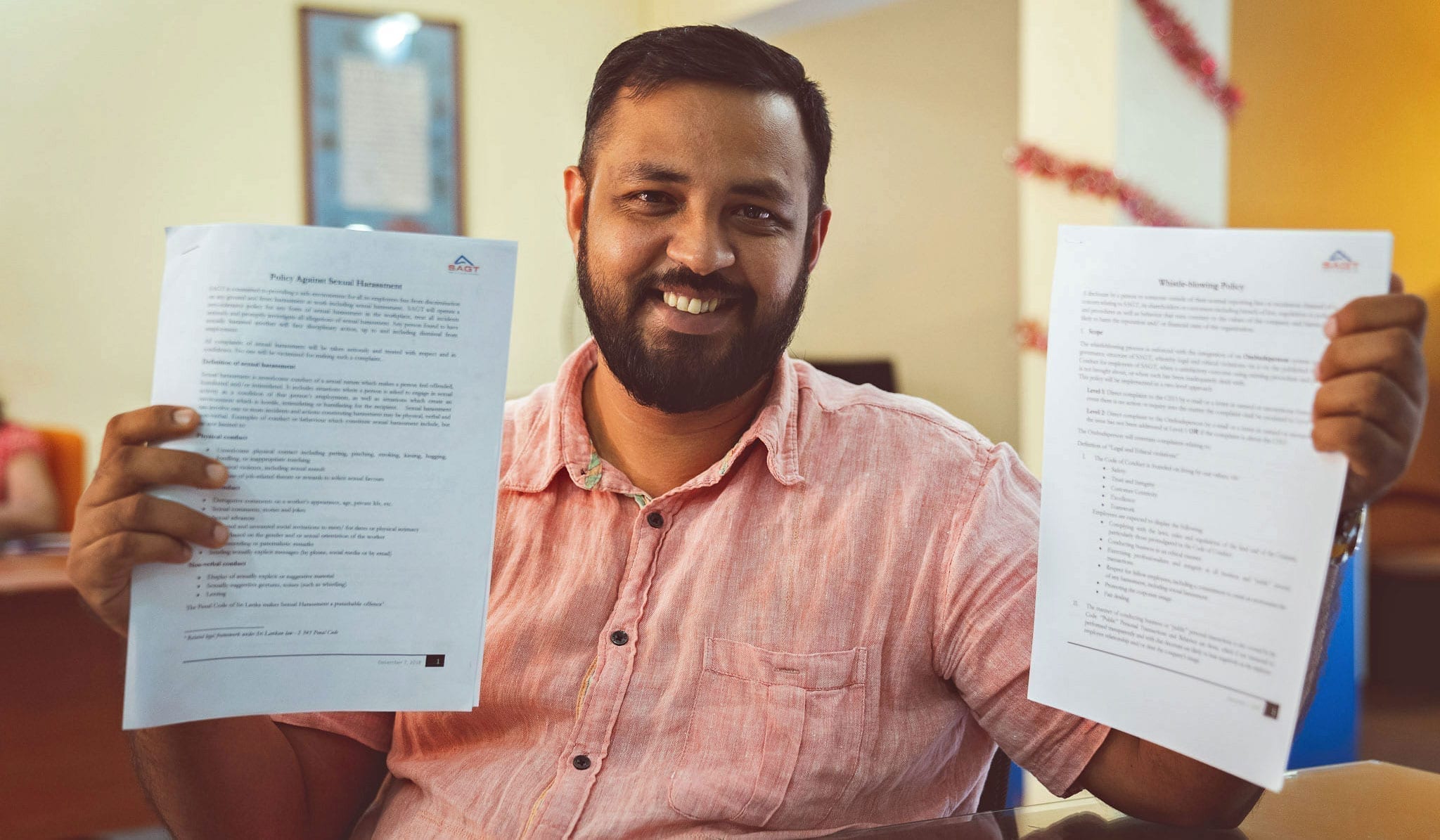

Union members in Sri Lanka celebrate a new workplace policy addressing sexual harassment. Credit: Solidarity Center/Sean Stephens

The effort was inspired by a Solidarity Center awareness-raising training in December on gender-based violence at work in which four workers from the South Asia Gateway Terminal (SAGT)—Ansley De Bruin, Mayura Kanchana, Nilanka Rathnayake and Ruwan Weerasinghe—took part. SAGT operates in Colombo’s shipping port.

“We have spoken to our [human resources] department many times over the past two years on setting a policy against gender-based violence in the workplace,” says Ansley De Bruin, youth wing president of the National Union of Seafarers Sri Lanka (NUSS). “We realized that it would be a hard push to get a code of conduct put in place regarding gender-based violence, so we felt the best thing to push for would be a whistleblower policy.”

After the training, the four participants again met with human resources. Based on their proposal, the organization not only introduced a whistleblower policy a couple of weeks later but also released a separate policy against sexual harassment.

Credit: Solidarity Center/Sean Stephens

The training program outlined incidences that constitute gender-based violence at work and the actions union members can take in supporting the adoption of a global ILO convention (regulation) on gender-based violence in the workplace. It was organized by the National Union of Seafarer’s Sri Lanka (NUSS), along with the International Labor Organization (ILO), International Transport Workers Federation (ITF) and Solidarity Center.

De Bruin says he is grateful SAGT understands its workers’ fundamental rights to a safe, violence-free workplace.

“This is not only a victory for the union but also for the organization and its staff. I would like to thank my organization the South Asia Gateway Terminal for hearing and implementing a system that protects all its staff.”

Mar 28, 2019

Recent massive teacher protests in Morocco demanding the government create permanent employment contracts is not an issue confined to the education sector—the extent to which decent jobs are available affects the future of the country, say leaders of the Democratic Labor Confederation (CDT).

A recent government decree making it no longer possible for workers with renewable two-year employment contracts to integrate into the public sector as before means workers have no access to fair wages and social benefits like retirement. The move “outlines the direction and policies of the state to dismantle the public service as a right of citizenship and to disengage from its responsibility towards citizens,” according to a CDT statement.

At least 10,000 teachers protested Sunday in Rabat, Morocco’s capital, to demand the government replace renewable contracts with permanent jobs that offer civil-service benefits, including a better retirement pension.

The Sunday protests came hours after police used water cannon to disperse an overnight demonstration. Many teachers had spent the night in the streets of Rabat after the first event before marching on Sunday from the education ministry to Parliament.

The weekend protests follow nationwide strikes in the education sector on March 13 and 14, and union leaders say more protests are likely.

More than 25% of Young Workers Are Employed

While overall unemployment hovers around 10 percent, more than one-quarter of young people in Morocco are without jobs.

Half of Moroccans who have jobs work in the informal economy, generally in precarious positions with low wages on farms, in construction, textiles and in the food and tobacco industry.

“Despite the strong opposition of the unions, the government is determined to continue hiring with contracts in the education sector and in the public sector in accordance with the recommendations of the international financial institutions, which demand a reduction in the wages,” the Moroccan Labor Union (UMT) says in a statement.

International lenders are pressuring Morocco to trim civil-service wages and cut back on public-sector services.

In addition to CDT and UMT, other unions supporting the march include the Democratic Federation of Labor (FDT), General Union of Moroccan Workers (UGTM) and the National Teaching Federation (FNE).

Mar 28, 2019

In Gulf Cooperation Council countries—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates—amnesties for workers in irregular status are frequently declared, indicating that irregularity is a common and recurring phenomenon within the governing kefala, or work-sponsorship, system. However, even if implemented perfectly, amnesty is a temporary fix, and effective solutions to reduce the population of undocumented migrant workers requires adherence to labor rights principles, according to a new report by the Solidarity Center and Migrant-Rights.org.

The GCC countries are characterized by a majority migrant workforce, tied to their employer-sponsors through kefala. However, for workers whose sponsors fail to renew work visas or for workers who are duped by fake jobs in the recruitment process or who land in untenable and abusive situations, workers “face a series of narrow, unenviable choices and are systematically denied freedoms enshrined in international human rights law,” says the report, Faulty Fixes: A Review of Recent Amnesties in the Gulf and Recommendations for Improvement.

In fact, the report adds: “Migrant workers who are unable to legally leave their job, or leave the country in some cases, are vulnerable to a range of abuses including occupational safety and health violations and gender-based violence as well as non-payment of wages and other forms of forced labor.”

The report has a variety of recommendations for countries of origin and Gulf nations to improve working conditions for migrant workers and to minimize factors that push them into irregular status. Among them: planning and communicating about an amnesty with migrant worker embassies and communities; investigate absent or abusive sponsors; and informing workers about their rights.

See the full report in English and Arabic.