Sep 21, 2020

To promote youth civic engagement and the fair employment of women, workers with disabilities and those migrating outside the country to earn a living, the Solidarity Center’s second annual School of Young Leaders in Bishkek educated dozens of young people in mid-September about their protections under the country’s labor code, with a special focus on disability rights. Event attendees—selected from around the country based on a writing competition—included youth and mentors with disabilities.

“This is my first experience in the framework of an inclusive society—where no one divides into some groups, everyone supports each other, accepts each other equally and shares their experiences,” said Sezim Tolomusheva, organizing and socioeconomic protection lead specialist for the Union of Textile Workers of Kyrgyzstan.

During a session covering how to engage traditional and social media, local disability-rights activist and blogger Askar Turdugulov encouraged attendees to pursue their goals despite limitations, such as the spinal injury that impaired his ability to walk from age 18.

“This [event] is a bright example in the promotion of the principle of ‘equal opportunities for all’ that gives equal labor rights for all people, regardless of their origin, gender or health status,” said Turdugulov.

Participating NGOs, trade unions and government agencies also provided young attendees—many of whom work directly to aid migrant workers and some of whom may one day migrate for work—with information about common challenges for migrant workers, the protective role of the Kyrgyz Migrant Workers’ Trade Union, the importance of pre-departure trainings and information about labor laws in destination countries. Other highlights included discussion on the rights of women at work under national legislation and the International Labor Organization’s 2019 Convention: Eliminating Violence and Harassment in the World of Work (C190). NGOs contributing expertise to the event included the “Equal Opportunities” Social Center and the Public Association of Girls with Disabilities, Nazik-Kyz.

Many young people feel forced to migrate in search of work, primarily to Russia and Kazakhstan, although also further to South Korea, Turkey or other countries. Kyrgyz migrant workers provide more than one-third of the Central Asian country’s GDP in money they send home. When workers migrate from Kyrgyzstan, they often face discrimination, exploitation and unsafe working conditions. Many are at risk of being trafficked and subjected to forced labor.

Kyrgyzstan ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) on February 7, 2019. The primary work needed for CRPD implementation will be expanding access for people with disabilities to education, justice and employment opportunities, physical therapy and rehabilitation services, medical and social assistance, and ensuring their free movement through promotion of universal design.

Aug 27, 2020

In a joint effort to protect market vendors and workers and reduce community spread of COVID-19, Kenya’s labor federation, Central Organization of Trade Unions (COTU-K), last week provided three of its affiliates with infection control supplies for distribution through the informal worker organizations that they represent. Under the August 13 “COTU CARES” campaign, six organizations that represent almost 6,000 informal workers are distributing to their Nairobi-based members, with Solidarity Center support, 4,000 KN95 face masks, 2,000 pairs of disposable surgical hand gloves, 100 pairs of industrial hand gloves, 140 gallons of liquid handwashing soap, 100 soap containers, 46 gallons of hand sanitizer, 36 handwashing stands and nine thermal body temperature scanners.

“Many people think that trade unions only represent formal workers, but now you know that informal workers are equally important and that’s why we are here,” said Rose Omamo, general secretary of the Amalgamated Union of Kenya Metal Workers (AUKMW), which helps represent automobile mechanics.

Recipients of the distribution include informal worker organizations Grogon-Ngara Food Vendors Association, metal worker associations Ambira Jua Kali and Migingo Mechanics Self Help Group, Muthurwa Cleaners Association, Muthurwa Food Court Vendors Association and street vendor association Nairobi Informal Sector Confederation (NISCOF). COTU-K affiliate participants include AUKMW, the Kenya Long Distance Truck Drivers Union (KLDTDU), the Kenya Union of Commercial, Food and Allied Workers (KUCFAW) and the Kenya Union of Domestic, Hotels, Educational Institutions, Hospitals and Allied Workers (KUDHEIHA).

Given the prominence of market shopping in Kenyan citizen’s daily lives—96 percent of the country’s retail is informal—together with relatively high infection rates of market vendors, infection control at markets is essential for containment of the pandemic. Scientists surveying about 10,000 people in Mozambique last month found that market vendors had the highest rate of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2—the virus that causes COVID-19—followed by healthcare workers.

COTU-K and its affiliates are addressing the pandemic on several fronts, including advocating with the Kenyan government to ensure informal worker access to government-provided COVID-19 relief measures such as food support and cash transfers. Solidarity Center partners AUKMW, KUCFAW and KUDHEIHA together with the Kenya Long Distance Truck Drivers Union (KLDTDU) are advocating for measures to protect cashiers and other workers exposed to the public. COTU-K and its affiliates are conducting several pandemic relief drives, including food and PPE distribution to flower workers in Isinya, Kajiado County, with the Kenya Plantation and Agricultural Workers Union (KPAWU) on August 17.

The pandemic has thrown systematic inequality in the Kenyan workforce into stark relief. As compared to the fewer than 3 million people who work in the formal sector, Kenya’s nearly 15 million informal sector workers—the majority of whom are women—historically have few legal protections. Most informal-sector workers, which include domestic workers and cleaners, market and street vendors, mechanics and security guards, are not covered by national safety and other employment regulations and have no access to government social programs such as social security, healthcare and unemployment benefits. Last year COTU-K affiliate trade unions representing Kenya’s formal-sector workers in food, health, education and metals signed memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with informal worker associations in their respective sectors in order to bring 5,600 newly organized informal-sector workers under the country’s legal framework that protects formal workers.

Jul 2, 2020

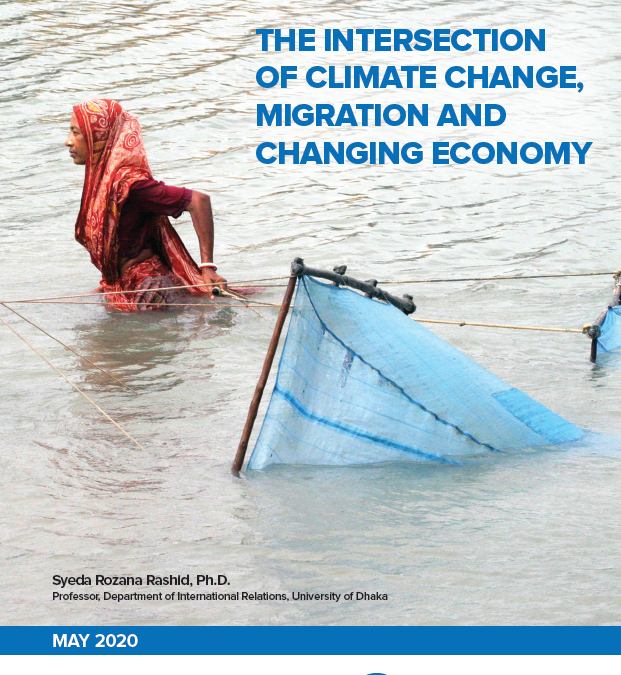

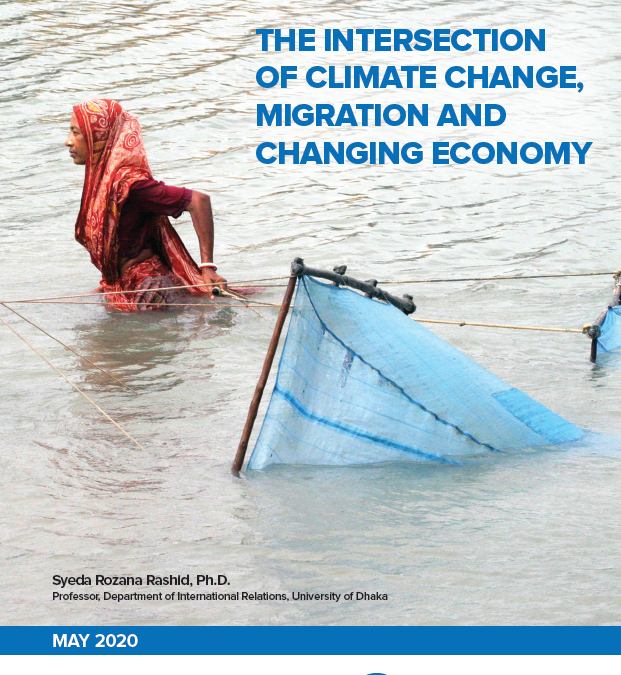

Underscoring the immediate risk of severe climate-induced weather events in South Asia, Cyclone Amphan last month slammed into the coast of eastern India and southern Bangladesh, destroying thousands of homes and killing at least 88 people. A new Solidarity Center report points to other, longer-term risks for workers in the region as a result of climate change, including forced job changes and migration, and increased economic vulnerability.

As many as one in every seven–or at least 16 million—people in Bangladesh could be on the move by 2050, potentially causing the largest forced migration caused by climate change in human history. Bangladesh is one of the 10 countries most vulnerable to climate change, at risk from climate disasters such as floods and cyclones. Situated on a floodplain, with a low-lying coastline and a host of rivers, the country and its people are threatened by rising sea levels, flooding, riverbank erosion, cyclones, storm surges and ever-hotter summers. These phenomena are exacerbated by climate change and contribute to loss of livelihoods, migration and poverty.

Against this backdrop, the Solidarity Center conducted a study investigating the intersection of climate change, economic activity and migration in Khulna and Jashore, Bangladesh. The study used primary and secondary sources of data, including surveys and first-person interviews with 50 Khulna- and Jashore-based workers who were employed in shrimp and fish processing and hatcheries, transport and domestic work sectors, and returnee migrant workers.

The report finds that increased salinity and flooding has driven people of both areas into new economic activities—primarily away from previously profitable farming into poverty-wage, non-farm economic activities that study participants describe as a hand-to-mouth existence. Cross-border migration of people from Khulna and Jashore to India for better economic prospects was found to be common and recurring, with international migration growing. Workers forced to transition into new jobs were found to lack information, training and financial resources to adapt to employment changes, and were mostly relying on friends and family for information and other types of resources to find new jobs. There was a low level of understanding about climate change and how it impacts their own livelihoods and the local economy.

“Climate change is forcing already-vulnerable people into often exploitative, precarious and poorly paid work, including migrating abroad for unsafe jobs where their rights are often unprotected,” says Solidarity Center Senior Program Officer Sonia Mistry.

The report offers recommendations to mitigate the impact of climate change on workers in the region, including raising awareness among residents about the impact of climate change; devising strategies to recover bodies of water and develop equitable and sustainable land-use solutions; providing skills training for workers; and reducing wage discrimination between women and men.

Jun 15, 2020

Domestic workers—at great risk during the pandemic crisis—are mobilizing to secure rapid relief and protection says the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF). This International Domestic Workers Day, more than 60 million of the world’s estimated 67 million domestic workers, most of whom are women of color working in the informal economy, are facing the pandemic without the social supports and labor law protections afforded to workers in formal employment. And, during a period of heightened infection risk, tens of thousands of migrant domestic workers are being forced to live in their employers’ homes, housed in crowded detention camps or have been sent home where there are no jobs to sustain them or their families.

The health and economic risks to domestic workers during the pandemic and compulsory national lockdowns are high. At the margins of society in many countries, most domestic workers are excluded from national labor law protections that require employers to provide paid sick leave and mitigate workplace infection risks through provision of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and appropriate social-distancing measures. And, if they get sick, many domestic workers cannot access national health insurance schemes.

“Domestic workers are among those most exposed to the risks of contracting COVID-19. They use public transport, are in regular contact with others… and don’t have the option of working from home, especially daily maids,” says Brazil’s national union of domestic workers, FENETRAD.

Without adequate personal savings due to poverty wages, many domestic workers and their families are suffering food insecurity because of income interruption or job loss.

“We can’t have many domestic workers left out in the cold,” says Myrtle Witbooi, founding member and first president of IDWF, and general secretary of the South African Domestic Service and Allied Workers Union (SADSAWU).

“Let us shout out to the world: We are workers!” she says.

Domestic workers have long shared their experiences with the Solidarity Center, detailing their long working hours, poverty wages and violence and sexual abuse. During the pandemic, additional sources of economic peril and health risks are being reported, including:

- In Mexico, where 2.2 million women are domestic workers, most of them are being dismissed without compensation. In a recent survey of domestic workers, the national domestic workers union SINACTRAHO found that 43 percent of those surveyed suffered a chronic condition like diabetes or hypertension, increasing their vulnerability to COVID-19.

- The United Domestic Workers of South Africa says their members report that some employers refused to pay wages during the country’s compulsory lockdown unless staff agreed to shelter in place with their employer, and that domestic workers who could not report to work were not paid.

- In Asia, women performing care work were excluded when countries launched COVID-19 responses and stimulus packages, says Oxfam.

- In the Latin American region, where millions of people who labor in informal jobs rely on each day’s income to meet that day’s needs, the pandemic lockdown is causing an economic and social crisis.

- Globally, unemployment has become as threatening as the virus itself for the world’s domestic workers, reported the ILO in May.

Meanwhile, migrant domestic workers—who often leave behind their own children to care for others to support their own families back home—are in peril. Some are being sent home without pay, some are subject to wage theft. Others are being quarantined by the thousands in dangerously crowded conditions or in lockdown in countries where they do not speak the language and have little access to health care, local pandemic relief or justice. For example:

- Thousands of Ethiopian domestic workers are stranded in Lebanon by the coronavirus crisis.

- At least one-third of the 75,000 migrant domestic in Jordan had lost their incomes and, in some cases, their jobs only one month into the pandemic.

- For millions of Asian and African migrant domestic workers in the Middle East, governments restrictions on movement to counter the spread of COVID-19 increased the risk of abuse, reports Human Rights Watch.

- Several Gulf states are demanding that India and other South Asian countries take back hundreds of thousands of their citizens. Some 22,900 people were repatriated from the UAE by late April, many without receiving wages for work already performed.

On June 16, International Domestic Workers Day, we honor the majority women who perform vital care work for others. Every day, and especially during the pandemic, the Solidarity Center is committed to supporting the organizations that are helping domestic workers attain safe and healthy workplaces, family-supporting wages, dignity on the job and greater equity at work and in their community.

“International Domestic Workers Day is a great opportunity to talk about power and resistance, and how we survive now and build tomorrow,” says Solidarity Center Executive Director, Shawna Bader-Blau, who applauds actions by all organizations dedicated to supporting and protecting domestic workers during the pandemic. These include:

- Domestic workers who are leaning into organizing and advocacy efforts during the pandemic, including in Peru, where they won the right to a minimum wage and written contracts by challenging the constitutionality of failing to implement the ILO domestic workers convention after ratification; in the Dominican Republic, where they mobilized to register 20,000 domestic workers into the social security system and lobbied for their inclusion in government aid, gaining new members in the process; in Brazil, where they successfully fought to remove domestic workers from the list of “essential workers” to limit their exposure to COVID-19 because of their limited safety net.

- In Bangladesh, BOMSA, a migrant rights nongovernmental organization (NGO), is creating and distributing COVID-19 awareness-raising leaflets specifically for migrant domestic workers returning to Bangladesh from abroad. Members are distributing soap, disinfectant and other cleaning supplies, and encouraging workers to maintain social distance. Another migrant rights NGO, WARBE-DF, is distributing COVID-19 awareness-raising leaflets to returned migrant workers and their communities. And as thousands of migrant workers return, the organization is engaging in local government coronavirus response committees to ensure inclusion of migrant-specific responses. Both are longtime Solidarity Center partners.

- Also in Bangladesh, in Konbari area—where garment workers who are internal migrants are not eligible for relief aid as it relies on voting lists for relief distribution—the local Solidarity Center-supported worker community center is connecting with local government officials and has provided nearly 200 names for relief, and is fielding more calls from internal migrant workers seeking assistance.

- In Brazil, which has more domestic workers than any other country—over 7 million—the National Federation of Domestic Workers (FENETRAD) and Themis (Gender, Justice and Human Rights) started a campaign calling for domestic workers to be suspended with pay while the risk of infection continues, or to be given the tools to protect against risk, including masks and hand-sanitizing gel.

- Also in Brazil, FENATRAD is providing legal and other advice by phone to domestic workers and delivering relief packages of food, medicines and protective gear, including masks, clothing, soap and hand sanitizer, to union members and their families.

- In the Dominican Republic, three organizations representing domestic workers successfully advocated with the Ministry of Labor for domestic workers’ to be included in the country’s COVID-19 relief program.

- In Mexico, to raise awareness and make the sector more visible, SINACTRAHO collected WhatsApp domestic worker audio messages about their experiences during the crisis for sharing on a podcast.

- The Alliance Against Violence & Harassment in Jordan, a Solidarity Center partner, is urging the government to grant assistance to migrant workers, who have little or no pay but cannot return to their country. The Domestic Workers’ Solidarity Network in Jordan shares information on COVID-19 and its impact on workers in multiple languages on its Facebook page

- The Kuwait Trade Union Federation urged the government to address the basic needs of Sri Lankan migrant workers, many of whom were domestic workers trapped in Kuwait after Sri Lanka closed its borders on March 19. Workers were eventually housed in 12 shelters while travel arrangements home were made.

- In Qatar, Solidarity Center partners Migrant-Rights.org and IDWF in April helped launch an SMS messaging service in 12 languages to provide tips to migrant domestic workers on COVID-19 and how to protect their rights.

- In South Africa—where many domestic workers suffer deaths and crippling injuries without compensation because they are excluded from the country’s occupational injuries and diseases act (“COIDA”), according to a recent Solidarity Center report—trade unions are demanding that employers provide their domestic workers with adequate PPE.

The Solidarity Center has joined its partners, the Women in Migration Network (WIMN) and a coalition led by the Migrant Forum in Asia, in urging governments and employers to uphold the rights of migrant workers, including migrant domestic workers.

Without urgent action to provide relief to workers in informal employment, including those providing domestic work, quarantine threatens to increase relative poverty levels in low-income countries by as much as 56 percentage points according to a new brief from the UN’s International Labor Organization (ILO).

Jun 3, 2020

Trade unions around the world are raising the alarm as some governments and employers during the coronavirus pandemic are failing to meet their obligation to protect workers’ health and safety in violation of international agreements and hard-fought-for national legislative frameworks that provide workers with the means to secure safer and healthier workplaces.

Workers in health care and other sectors are demanding that governments and employers take steps to protect workers, including recognition of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) as an occupational hazard and COVID-19 as an occupational disease. The ITUC, on UN World Day for Safety and Health at Work, said that recognition will ensure for workers the right to representation and occupational safety and health (OSH) rights and the application of agreed-upon measures to reduce risk, including the right to refuse to work under unsafe working conditions.

Healthcare workers are particularly imperiled on the front lines of the COVID-19 outbreak, given their vulnerability to pathogen exposure, long working hours, psychological distress, fatigue, occupational burnout, stigma and physical and psychological violence. On April 28, UN World Day for Safety and Health at Work, the World Health Organization (WHO) called upon governments, employers and the global community to take urgent measures to strengthen their capacity to protect the health and safety of health workers and emergency responders, and to respect workers’ right to decent working conditions especially during the pandemic.

“We just want to be able to do our job safely,’ says a Hussein University hospital doctor in Cairo, Egypt.

Amid continuing shortages of protective equipment, at least 90,000 healthcare workers worldwide are believed to have been infected with COVID-19, and perhaps twice that, said the International Council of Nurses (ICN) earlier this month. Health workers around the world are at risk from preventable infections and other job-related dangers during the crisis. For example:

- Algeria doctor Wafa Boudissa—denied early maternity leave three times by hospital management in contradiction of a presidential decree protecting pregnant women–died at age 28 last month, at eight months pregnant.

- In Brazil, nurses are dying as the pandemic overwhelms hospital, even while the government downplays the contagion.

- Medical staff in Cameroon are asking for additional security at hospitals following a series of attacks by people upset that they or their loved ones were diagnosed with the coronavirus.

- In the impoverished North Caucasus republic Daghestan, more than 40 healthcare workers are reportedly dead of COVID-19, although officials claim they did not all die from coronavirus.

- Medical workers in Egypt are describing dangerous workplaces in which personal protective equipment (PPE) is in short supply and too few COVID-19 tests are available to workers and patients. About 13 percent of those infected in Egypt are medical professionals, according to the UN’s World Health Organization (WHO). 19 doctors have reportedly died so far from the disease.

- Doctors, nurses and laboratory technicians among others in Lesotho deemed themselves unable to work following multiple failed attempts to engage authorities on how to obtain protective gear, provide payments for health care workers contracting COVID-19 and providing a risk allowance for those treating COVID-19 patients.

- In Mexico, health care workers are facing violent attacks by members of the public who fear contagion as well as by family members angered by news of a loved one’s infection or COVID-19–related death. Medical workers have been chased from their homes, doused in bleach and beaten. Following false reports of intentional transmission of the coronavirus by medical personnel, citizens blocked highways and roads in the municipalities of Ciudad Hidalgo, Tuxpan and Zitácuaro.

- 27 doctors and 20 nurses are reported dead in Indonesia. With 3,293 infections and 280 deaths, Indonesia has the highest death toll in Asia after China, although health experts fear it could be much higher.

- In Kaduna State, Nigeria, government threatened mass dismissals of health workers who choose not to report for work during the pandemic, even though they report inadequate PPE and the government recently cut their salaries by 25 percent.

- In Pakistan, after police arrested more than 50 doctors demanding PPE, dozens of doctors and nurses went on a hunger strike to demand safety equipment and protest the infection of 150 medical workers and deaths of several, including that of a 26-year-old doctor who had just begun his medical career.

- Medical workers in Russia are dying 16 times more often than in countries with comparable coronavirus outbreaks; health care workers there comprise 7 percent of COVID-19 fatalities, according to Russian media outlet Mediazona; medical workers’ own list numbers healthcare-worker fatalities at 240.

Not only those working in the health sector are at risk, say trade unions, given that many of the world’s workers must continue to physically report for work because they do not have savings to sustain a lengthy quarantine, they do not want to lose their jobs or their work has been categorized essential. For example:

- In Bangladesh, against Ministry of Health advice and during the country’s coronavirus lockdown, tens of thousands of garment workers returned in late April from far-flung homes to crowded, factory-based dormitories to jobs in factories that mostly lack adequate infection control measures. In an attempt to deliver pending orders to global clothing brands, about half of Bangladesh’s 4,000 garment factories have reopened.

- After exposure to a single infected worker in Ghana, 533 factory workers at a fish-processing plant in the port city of Tema tested positive for the coronavirus, representing more than 11 percent of Ghana’s total COVID-19 infections to date.

- More than 200 textile workers at an export-focused plant in Guatemala tested positive last week for the novel coronavirus, with more results pending; testing was forced on the employer after reports surfaced that infected workers were continuing to work and the company was not taking protective measures.

- At some apparel factories in Honduras workers were expected to continue to work in violation of the government’s lockdown order, including at a plant where 2,400 workers make T-shirts and sweatshirts for export.

- Mexico oil company Pemex and the country’s Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) together had 1,245 confirmed cases by mid-May. Pemex alone reported 1,092 cases and 141 deaths as of last week: an average rate of infection of 20.7 people per day and 2.5 daily deaths.

- A number of firms in Mexico continue to produce goods for the U.S. market despite coronavirus lockdown rules, putting their workers in grave danger of contracting COVID-19.

- In South Africa, which has the most cases of coronavirus in Africa, an outbreak closed Mponeng gold mine after 164 cases of coronavirus were detected there last week despite working at 50 percent capacity. The South African Human Rights Commission (the SAHRC) warned employers that failure to failure to implement precautionary measures to protect workers from contracting COVID-19 would constitute a human rights violation under the South African constitution, and be pursued as such by the Commission with other statutory regulatory bodies.

- Worldwide, migrant workers clustered in low-wage, informal sector jobs in high-density living conditions or engaged in care work in close quarters with their employers are succumbing in higher numbers to infection as compared to local populations. Last month, Saudi Arabia sent home nearly 3,000 of the estimated 200,000 Ethiopians living there before the United Nations called for a halt.

There were at least 5,546,000 cases and 347,000 deaths reported in at least 180 countries worldwide in the COVID-19 pandemic as of May 26, 2020, according to data compiled by Johns Hopkins University.