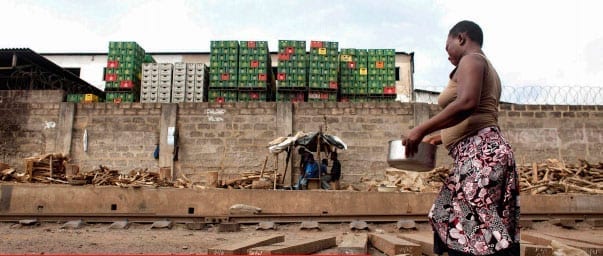

In the photo, a Ghanaian street vendor sells her wares in front of a massive multinational brewing company.

Guess who pays more in taxes?

The image, an ActionAid photo, shows the inequity of an impoverished vendor paying more in taxes than a major multinational, and makes concrete the reality of illicit financial flows for millions of Africans.

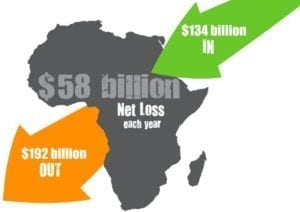

Africa loses at least $50 billion annually, likely much more, through illicit financial outflows, an amount equal to the development assistance it receives each year. Meanwhile, the number of people living on less than $1.25 a day is estimated to have increased from 290 million in 1990 to 414 million in 2010, according to a report commissioned by former South African President Thabo Mbeki. The report defines illicit financial flows as “money illegally earned, transferred or used.” The definition also encompasses the socially undesirable, such as the multinational corporate tax avoidance.

“The problem with IFFs in Africa is that money flows out of Africa and it never flows back,” says Luckystar Miyandazi, policy officer in the African Institutions Program at the European Center for Development Policy Management (ECDPM).

“When illicit financial flows happen, especially in Africa, there is a deficit of taxes,” she says. “Governments find ways of raising this money because they still need money to run, so that means increases in basic goods and services. [Higher] taxes on food, milk and so on affects workers, the community.”

Such regressive tax policies disproportionately harm informal workers and people living in poverty—the majority of whom are women.

Africa Delegation Travels US to Discuss Illegal Financial Flows

“The nature of investment we see that comes to Africa drives the race to the bottom”—Joel Odigie

Miyandazi is part of a four-person Solidarity Center delegation to the United States this month seeking to shine a light on the massive, yet little recognized crisis of illegal financial flows. The group spoke Monday at a panel on the University of California, Berkeley campus, and at a session sponsored by the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s Africa Braintrust in Washington, D.C., on Friday.

“The nature of investment we see that comes to Africa drives the race to the bottom,” says Joel Odigie, a member of the delegation and coordinator of Human and Trade Union Rights at the International Trade Union Confederation-Africa (ITUC-Africa). “There’s an attraction for financial direct investment, and business asks for benefits and concessions,” including lower labor standards, which drives down opportunities for good jobs. The result, says Odigie, is increasing numbers of working poor. (Odigie also spoke on the ITUC’s Radio Labor.)

“Work is on behalf of dignity—if you work, you get out of poverty,” he says. Yet “so many persons are working, breaking their backs, but they’re still in poverty.”

African trade unions and civil society organizations are leading this discussion and have responded with initiatives such as the launch of a transnational movement, Stop the Bleeding Africa, to educate around IFFs and mobilize citizens to advocate for corporate and government accountability.

African trade unions and civil society organizations are leading this discussion and have responded with initiatives such as the launch of a transnational movement, Stop the Bleeding Africa, to educate around IFFs and mobilize citizens to advocate for corporate and government accountability.

“For us the campaign around illicit financial flows is basically trying to make our members understand what the IFF is all about and bringing the message home—how this directly affects workers,” says Caroline Mugalla, executive secretary of the East Africa Trade Union Confederation (EATUC) and a delegation member. (Mugalla also spoke on the ITUC’s Radio Labor.)

Using Tanzania as an example, Mugalla says she points to the $4.8 billion Tanzania loses each year in illegal financial flows, and describes for people how that money could be used to improve the health delivery system and ensure children have access to education.

“Then people get it,” she says.

Going Forward

Mugalla says unions also are connecting with local government leaders to make the connection between the financial outflows and their struggle to provide basic services.

“A community has no water, no paved roads, no electricity—but the nearby mining company has it all,” she says.

When making tax policy, governments “need to take into account the people at the lowest level,” says Miyandazi. “For example, when a government gives a mining contract to a company and it’s going to displace people, governments should put people first and not multinationals.

The bottom line, says Miyandazi: “When making policy on Africa, Africa should be sitting at the table, part of the people who inform this policy and not be done by other people who think things should be done for Africa,” she says.

Gyekye Tanoh, team leader of the Policy Economy Unit at Third World Network Africa, also is taking part in the delegation.