When Rafikul Islam, 25, president of a workers’ welfare association at a factory in the Dhaka export processing zone (EPZ) heard that one of the top factory officials harassed the female staff member responsible for the factory’s day care center, he took action.

“We called a meeting of our association and decided that we would protest this incident and write to the authorities to take action against the official,” Rafikul says. After they lodged a complaint, the official was terminated.

“This was possible because we were united. We never imagined such immediate action when there was no union in the EPZ.” Rafikul said there were similar incidents in other factories in the past but the victims did not get justice.

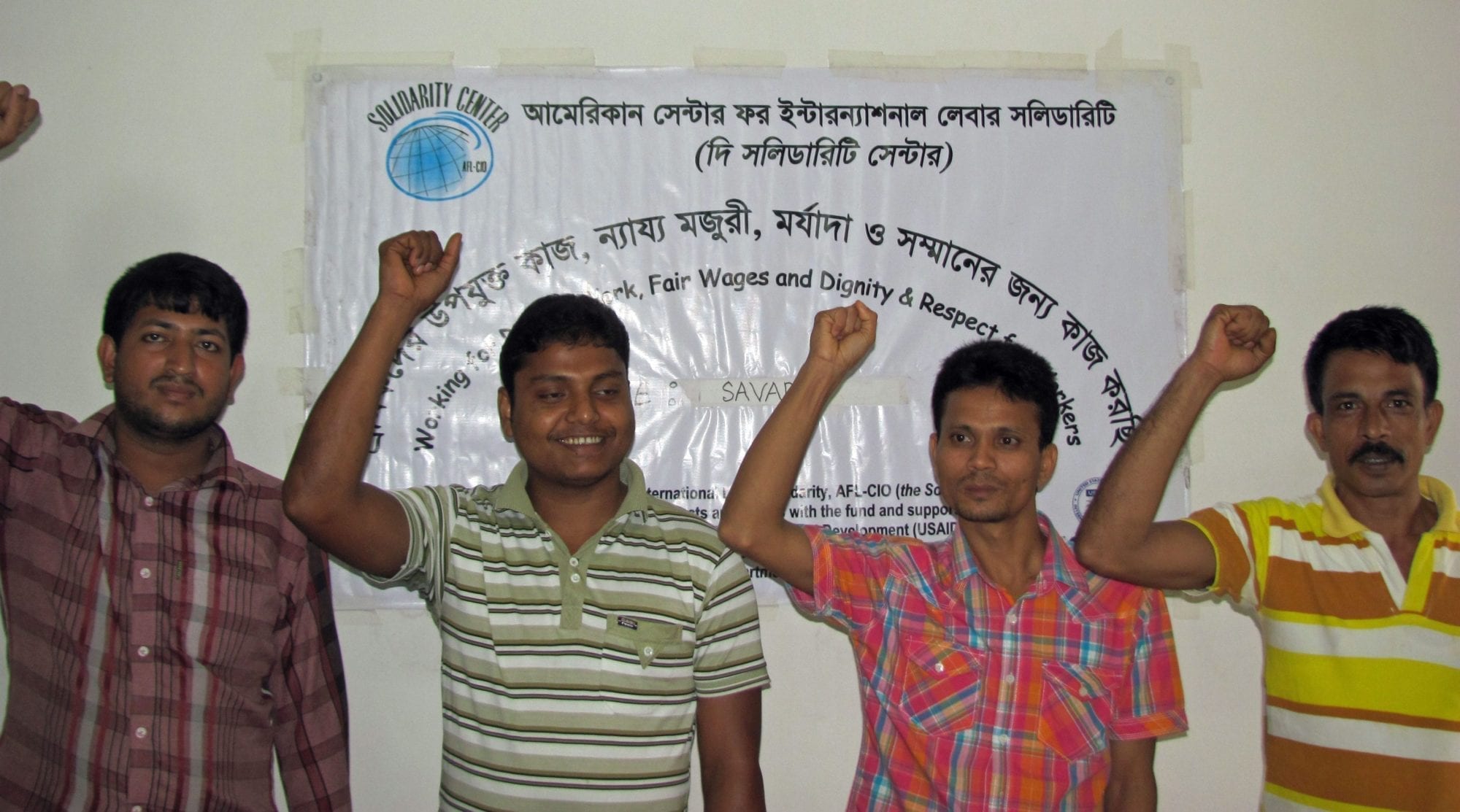

Despite obstacles, workers’ welfare associations are gaining ground in factories throughout Bangladesh’s export processing zones. Bangladesh derives 20 percent of its income from exports created in the EPZs, which are industrial areas that offer special incentives to foreign investors like low taxes, lax environmental regulations and low labor costs. Some 377,600 workers, the vast majority women, work in 497 factories in Bangladesh’s eight EPZs.

EPZ workers had long been denied the freedom to form unions, but in 2010, a law passed enabling workers to form unions under a different name—workers’ welfare associations. Associations are permitted to represent workers on disputes and grievances, negotiate collective bargaining contracts and collect membership dues. Now in the Dhaka EPZ alone, 40 of the 103 factories include workers welfare associations.

But unlike traditional unions, the associations cannot interact nor affiliate with any labor union, nongovernmental organization or political organization outside the EPZ. Associations can only form a federation within one zone.

Kholilur Rahman, 20, general secretary of an association of another factory in the Dhaka EPZ says that after forming an association, workers became aware of their legal rights.

“Most of the workers in our factories were contractual workers,” he says. “Authorities did that purposefully to deprive us from receiving benefits. But after forming the association, the factory management made us permanent,” Kholilur said.

Oliur Rahman, a member of an association in the Dhaka EPZ, says that in the past, managers terminated them for trivial reasons.

“But this is not the case after we formed an association and voted for our association and elected the officers for our workers’ welfare association,” he said.